We are thrilled to announce that Jennifer Frangella has joined Irwin IP as a Senior IP Litigation Paralegal. With extensive experience in the legal field, Jennifer will be a valuable asset to our team, assisting in all aspects of intellectual property and technology-related litigation.

Jennifer brings a wealth of knowledge in managing complex litigation cases, including discovery, motion practice, claim construction, expert discovery, arbitration, trial, and appellate proceedings.

We look forward to the positive impact Jennifer will bring to our team.

——–

Irwin IP specializes in mission-critical intellectual property and technology litigation, catering to a diverse client base, including Fortune 500 companies and innovative startups. Our expertise extends to enforcing and protecting intellectual property portfolios, ensuring our clients’ product lines, worth hundreds of millions annually, remain secure. Notably, we routinely, successfully litigate against the largest, most prestigious law firms representing the largest companies in the world on matters valued in the tens and hundreds of millions.

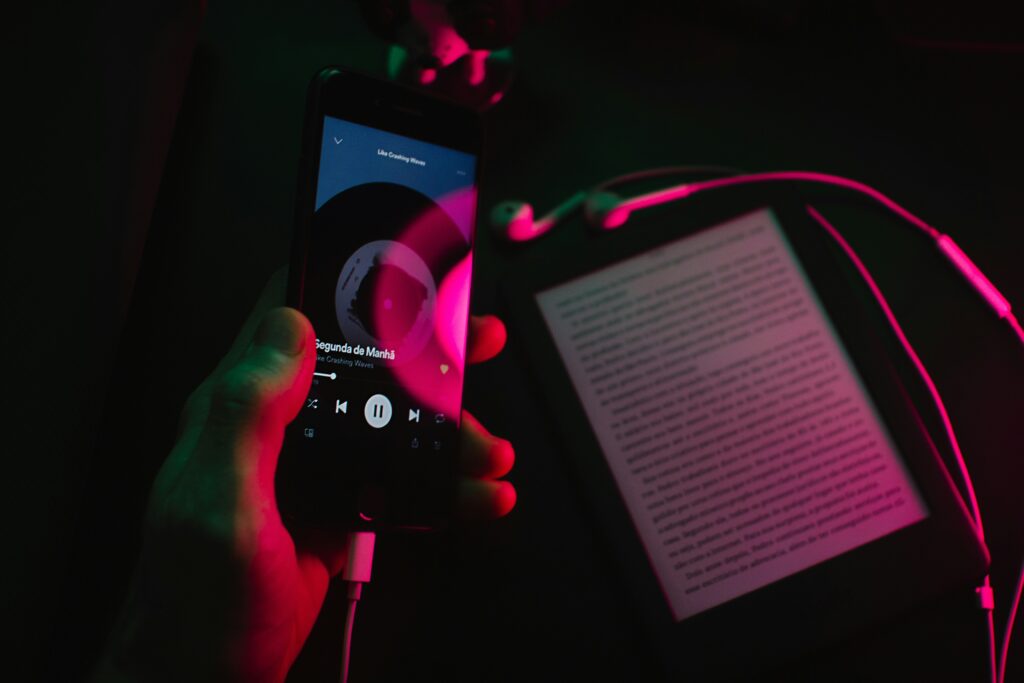

On January 29, 2025, the Southern District of New York dismissed a lawsuit filed against Spotify for allegedly failing to pay the appropriate royalties to songwriters. The Mechanical Licensing Collective (“MLC”), which collects royalties from digital streaming platforms on behalf of composition rightsholders, brought this suit after Spotify unexpectedly reduced its reported royalties. In defense, Spotify cited the Copyright Act, which regulates the collection and reporting of composition royalties under a statutory compulsory blanket license. The Court confirmed Spotify’s ability to exploit a loophole in the Copyright Act and avoid paying an estimated $150 million per year in royalties to songwriters.

Spotify is one of the largest music streaming services with its most popular subscription, Premium, having over 44 million subscribers. Under a statutory compulsory blanket license, Spotify is required to pay royalties to the MLC according to a formula outlined in the Copyright Act. That formula distinguishes between “Subscription Offerings” encompassing solely music streaming, and “Bundled Subscription Offerings” that include music streaming and an additional product or service that is greater than “token value.” All revenue obtained from Subscription Offerings must be reported to MLC, while a Bundle requires the reporting of the revenue based on the weight of the retail price of the musical component if it was sold as a standalone product, relative to the retail price of the bundle.1

MLC brought suit against Spotify alleging that its Premium plan does not fall under the definition of a Bundled Subscription Offering and, even if it does, the additional hours of audiobook access are not more than “token value.” In 2023 Spotify introduced 15 hours of audiobook listening to its Premium subscription but continued to report its royalties as a Subscription Offering. However, in 2024 Spotify reported its Premium subscription as a Bundle. MLC argued that Spotify improperly reduced the amount of royalties because it now only received royalties on a portion of the monthly subscription price, whereas Spotify previously reported the full amount. The Court reviewed the definition of Bundled Subscription Offering and found that Spotify’s Premium subscription qualifies as a Bundle because access to audiobooks is an additional product or service, and this audiobook access has more than “token value” in the “natural and ordinary meaning” of the term. Therefore, the Court dismissed MLC’s complaint.

By including audiobook access on their streaming platforms, Spotify discovered a loophole that allows it to pay less royalties to musicians even though its plan encompasses the same access to its musical repertoire. Because the Court allowed this, lawmakers will have to decide whether the law should be changed to prevent this type of pricing scheme in the future.

- In other words, if Spotify priced its music-only Premium subscription which qualifies as a Subscription Offering, at $10.00, it would be required to report $10.00 per month per subscriber. In contrast, if Spotify priced its music-audiobook subscription package, which qualifies as a Bundled Subscription Offering, at $18.00 per month, Spotify would be required to report only $9.00 per month per subscriber to the MLC. ↩︎

Irwin IP is pleased to welcome Lawrence Raia, a JD/MBA Candidate at Notre Dame Law School, as our pro bono intern for a ten-week internship. During his time with the firm, he will work alongside Alexa Tipton, Irwin IP’s Pro Bono Coordinator and Special Counsel for Entertainment Law and Pro Bono Services, on a variety of pro bono initiatives that align with our commitment to expanding access to justice.

Irwin IP believes that attorneys have a professional responsibility to use their legal expertise for the public good. Our firm is dedicated to this mission, with each attorney committing to a minimum of 80 pro bono hours annually. Through partnerships with organizations such as Lawyers for the Creative Arts, Chicago Volunteer Legal Services, and the Greater Chicago Legal Clinic, we provide legal assistance to those in need while fostering professional development among our attorneys.

We look forward to Lawrence’s contributions and are proud to continue our longstanding commitment to pro bono service.

——–

Irwin IP specializes in mission-critical intellectual property and technology litigation, catering to a diverse client base, including Fortune 500 companies and innovative startups. Our expertise extends to enforcing and protecting intellectual property portfolios, ensuring our clients’ product lines, worth hundreds of millions annually, remain secure. Notably, we routinely, successfully litigate against the largest, most prestigious law firms representing the largest companies in the world on matters valued in the tens and hundreds of millions.

On January 24, 2025, the Federal Circuit considered the “long mentioned but rarely applied” reverse doctrine of equivalents (“RDOE”) defense. The widely accepted doctrine of equivalents (“DOE”) allows plaintiffs to establish infringement when an accused element “matches the function, way, and result of the claimed element,” even if it is not exactly the claimed element. RDOE, which can be traced back to the 1800s, is the opposite: a defense allowing an accused infringer to avoid a finding of infringement by showing its accused product “has been so far changed in principle [from the patented invention] that it performs the same or similar function in a substantially different way.”1 In other words, the RDOE provides a rebuttal to literal infringement. It has been questioned whether the RDOE survived the Patent Act of 1952, and to date, the Federal Circuit has not affirmed any decision finding noninfringement based on RDOE nor has it ruled that RDOE is not a valid defense.

In Steuben Foods, a jury found infringement of a patented invention for filling sterile food containers using a valve to stop and start food flow. It includes a first sterile region and “a second sterile region positioned proximate said first sterile region.” Rather than the valve shaft moving into an unsterile location when closed, it moves into the second sterile region to prevent bringing contaminants into the first region. The accused system similarly provides sterility when the valve is both open and closed; however, it uses a flexible barrier mechanism. The District Court granted Shibuya’s motion for judgment as a matter of law, holding that (1) no reasonable juror could have found literal infringement, (2) Shibuya made a prima facia case of RDOE, and (3) Steuben’s expert witness’s testimony was wrong as a matter of law and entitled to no weight.

On appeal, Steuben argued that the 1952 Patent Act eliminated RDOE. Section 271(a) provides exceptions to infringement, and Steuben asserted that the language “[e]xcept as otherwise provided in this title” requires RDOE to be expressly enumerated in the statute. Steuben further contended that invalidation under § 112, not noninfringement under RDOE, provides the recourse for a claim alleged to be too broad. Shibuya countered that the Supreme Court has held that the 1952 Patent Act “left intact the entire body of case law on direct infringement,” and that the Supreme Court rejected Steuben’s argument when it held that the 1952 Patent Act “is not materially different from the 1870 Act with regard to claiming.”

The Federal Circuit found Steuben’s arguments compelling—and noted that it has never affirmed a decision finding noninfringement under RDOE—but held that it need not decide whether RDOE is still a viable defense under the 1952 Patent Act. Rather, the Federal Circuit faulted the District Court for failing to consider expert testimony. When viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to Steuben, the Federal Circuit held that “a reasonable jury could have found the principles of operation of the accused product…were not ‘so far changed,’ as to support a theory of noninfringement under RDOE” and reversed the District Court’s grant of judgment as a matter of law. The Federal Circuit declined to expressly affirm or denounce the availability of the RDOE defense and leaves the future for RDOE uncertain. However, one thing is clear: RDOE is not dead. Yet.

The Federal Circuit recently addressed a deceptively straightforward question: does a published U.S. patent application qualify as prior art as of the application’s filing date in inter partes review (“IPR”) proceedings? Lynk appealed the PTAB’s reliance as a prior art printed publication on a patent application filed before but published after Lynk’s patent based on the general requirement that printed publication be publicly accessible and interpretation of the statutory term “printed publication” based on 19th century case law. The Federal Circuit held that Congress created an exception from the broader public accessibility requirement and under the plain language of the Patent Act published patent applications are prior art for IPRs as of their filing date under § 102(e)(1), and not the date they became publicly accessible.

The dispute arose when, during an IPR, Samsung relied on a published U.S. patent application as prior art to challenge the validity of claims in Lynk’s patent related to alternating current driven light emitting diodes (LEDs). The PTAB upheld Samsung’s challenge, invalidating several claims, but Lynk argued on appeal that § 311(b) excludes references not publicly accessible before the priority date. In particular, Lynk contended that “patents or printed publications” in § 311(b) precludes reliance on a published application’s filing date under § 102(e)(1). The Federal Circuit decisively rejected this argument, holding that the date of when the patent application became publicly available is irrelevant; instead, it is the filing date that establishes the status of published patent applications as prior art under § 102(e)(1).

In reaching this conclusion, the Court emphasized that § 311(b) incorporates the prior art framework of § 102, which explicitly provides that a published U.S. application is prior art as of its filing date. The Court clarified that the term “printed publications” in § 311(b) was not meant to exclude those references. Instead, the statutory language reflects Congress’s intent to preserve the full scope of prior art recognized under § 102, ensuring consistency between IPR proceedings and other contexts of invalidity analysis.

Lastly, the Court addressed the broader implications of the statutory phrase “patents or printed publications.” The Court clarified that Congress historically excluded challenges to validity based on other grounds like public use and on-sale activities from IPRs. The Court reasoned that Congress intended to streamline proceedings and avoid substantial discovery or fact findings, which printed publications do not necessitate. Nonetheless, the exclusion was not meant to diminish the role of official USPTO publications, which include published patent applications. By affirming this interpretation, the Court reaffirmed the balance Congress sought to achieve between simplifying prior art analysis in IPRs and maintaining the integrity of established prior art categories.

This decision provides significant clarity for patent practitioners. It confirms that published patent applications can serve as prior art based on their filing date in IPRs, aligning with the longstanding principles of § 102(e)(1). In addition, it solidifies the reliability of published applications as a key tool for challenging validity.

In 2024, the patent law landscape underwent significant changes driven by landmark court decisions and the advent of emerging technologies. Major rulings from the Supreme Court, the Federal Circuit, District Courts, and the Patent and Trademark Office redefined existing patent frameworks, including a complete rewrite of the long-standing obviousness test for design patent invalidity.

This article delves into these developments, focusing on themes emerging at the Federal Circuit regarding design patents, damages, validity, equitable defenses, attorney’s fees, standing, and marking.

Additionally, we explore the future of intellectual property rights, focusing on the implications of artificial intelligence and the ongoing legislative debates surrounding patent law reform.

Don’t miss out on these crucial insights— download the full article below.

Irwin IP is pleased to announce that eight of our attorneys have been named as 2025 Illinois Super Lawyers by Thomson Reuters. This prestigious recognition highlights their dedication to excellence and their significant contributions to the field of intellectual property law.

Among those recognized as Super Lawyers are Robyn Bowland, Lisa Holubar, Barry F. Irwin, and Joseph Marinelli. This marks Barry’s 21st year as a Super Lawyer, where he joins a distinguished group of attorneys who have been consistently recognized since the very beginning. Additionally, we are proud to announce that Alexander Bennett, Victoria Hanson, Nick Wheeler, and Daniel Zhang have been recognized as a Rising Star, a recognition that only 2.5 percent of lawyers in the state of Illinois are named.

Congratulations to our exceptional team for this well-deserved acknowledgment!

——–

Irwin IP specializes in mission-critical intellectual property and technology litigation, catering to a diverse client base, including Fortune 500 companies and innovative startups. Our expertise extends to enforcing and protecting intellectual property portfolios, ensuring our clients’ product lines, worth hundreds of millions annually, remain secure. Notably, we routinely, successfully litigate against the largest, most prestigious law firms representing the largest companies in the world on matters valued in the tens and hundreds of millions.

In trademark disputes, the likelihood of confusion analysis—guided by the DuPont factors—is a balancing test with the fame of a mark often tipping the scales. The Federal Circuit highlighted this issue in its critique of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board’s analysis of the “Cognac” certification mark. In Bureau v. Cologne & Cognac Entertainment, the Cognac producers’ union and Institut National des Appellations d’Origine, the French certification agency, opposed the trademark application for “Cologne & Cognac Entertainment” for a hip-hop record label. The Board dismissed the Bureau’s opposition to the registration of the mark for failing to achieve fame as a certification mark. The Court uncorked its analysis by disagreeing with the Board’s findings on fame and its DuPont analysis. The Court also reviewed an issue of first impression—how to treat sales and advertising expenditures as evidence of fame when a certification mark is used alongside a house or product mark, e.g. Hennessy Cognac. Concluding that the case required another round, the Court vacated and remanded the Board’s decision.

While not a registered mark in the U.S., long-standing French standards have given Cognac a common law certification mark and protection under 27 C.F.R. § 5.145, prohibiting use of the term on spirits except for “[g]rape brandy distilled exclusively in the Cognac region of France which is entitled to be so designated by the laws and regulations of the French government.” So, to bear the Cognac name, a brandy must meet specific legal standards set by the Institut for the grapes used, distillation process, and aging.

The Court found the Board erred by requiring that Cognac be famous for its “certification status”—that “Cognac” conveys the liqueur is certified—rather than for other indications such as its geographic origin, quality, or method of manufacture. The Court concluded that not only was there no statutory requirement that consumers be aware of the certification status of a certification mark, but that such a requirement could be impractical and inconsistent with ordinary purchasing behaviors.

As an issue of first impression, the Court found the Board erred by relying on the ‘inconspicuous’ usage (small ‘cognac’ type on the bottle) to support a conclusion that sales were not ‘unequivocal[ly]’ linked to Cognac, and not Hennessy, for example. Instead, the Board should have considered context-specific evidence to determine whether a portion of the sales and advertising evidence could be attributed to the Cognac mark over the house or product mark, and thus indicative of the fame of the certification mark. Indicia of critical attention and the general reputation of a marked product—evidence present, but not properly credited—contradicted the Board’s findings. The Court highlighted that because fame is the dominant element for the likelihood of confusion analysis, the Board should reconsider all of the relevant DuPont factors on remand.

In 1998, the Institut successfully resisted the generification of the Cognac mark and, along with related unions, the Institut has been involved in various U.S. suits to shield their marks. Given how protective the Institut and the Cognac union have been over the certification mark, trademark applicants should be cautious of incorporating a famous certification mark into their own marks for different services or goods. The fame of the certification may carry significant weight in a likelihood of confusion analysis, even where the public is not aware of its certification purpose. As Snoop Dogg has noted, “Cognac is the drink that’s drank by Gs.” That type of fame may be difficult to counter.

Irwin IP is pleased to announce that after extensive negotiations while representing one half of a southern rock duo, War Hippies, in his dispute with the other member of the band’s LLC, Reid Huefner, Alexa Tipton, and Katie Schelli successfully secured our client’s buy-out of his former partner’s share and protected the integrity of the band LLC. A band agreement—in this case, an LLC Operating Agreement—governing the management and business practices of the band, is essential to ensure that the musical group can stay focused on what matters most – its music. A comprehensive agreement will cover ownership rights in the band’s intellectual property, voting rights, member responsibilities, disbursements, as well as how the members will handle the dissolution and wind-up of the band in the case of disbandment. Fortunately for our client, the band did have an agreement that governed many of the bandmembers’ disputes. However, it failed to adequately address winding-up of the band, the LLC, and associated member responsibilities, thus leading to heightened discord during those negotiations. Although it may feel uncomfortable to plan for the end while starting a new venture with close bandmates, a band agreement that governs everyday practices and disputes is often essential to maintaining a harmonic relationship and a long career as musical partners.

If you are part of a band that currently does not have an agreement, you should strongly consider creating one to protect your rights in both the art and business that you create. If you have any questions, please reach out to Alexa Tipton at [email protected].

——–

Irwin IP specializes in mission-critical intellectual property and technology litigation, catering to a diverse client base, including Fortune 500 companies and innovative startups. Our expertise extends to enforcing and protecting intellectual property portfolios, ensuring our clients’ product lines, worth hundreds of millions annually, remain secure. Notably, we routinely, successfully litigate against the largest, most prestigious law firms representing the largest companies in the world on matters valued in the tens and hundreds of millions.