Irwin IP LLP attorneys Lisa Holubar and Ariel Katz provide their insights on just how valuable pro bono work is. As discussed in the article, Providing pro bono legal services is of paramount importance for law firms as it upholds the fundamental principle of access to justice, ensuring that individuals who cannot afford legal representation are not denied their legal rights. By offering their expertise and resources to those in need, law firms contribute to a more equitable and just society.

Pro bono work allows attorneys to hone their skills, gain invaluable courtroom experience, and broaden their legal knowledge by taking on a diverse range of cases. This not only benefits the lawyers personally but also enhances the overall quality of legal services provided by the firm. Pro bono initiatives strengthen a law firm’s reputation and foster a positive public image, attracting clients who appreciate a commitment to social responsibility. Ultimately, by engaging in pro bono work, law firms demonstrate their dedication to the welfare of their communities and the principles of justice, promoting a stronger and more ethical legal profession.

To read the full article, visit: https://www.law360.com/pulse/articles/1567474

*This article is located behind a paywall and is only available for viewing by those with a subscription to Law360.

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) recently affirmed an Eastern District of Texas ruling that U.S. Patent No. 8,191,091 (“the ’091 patent”) is unenforceable due to prosecution laches. Personalized Media Communications, LLC (“PMC”) was found to have engaged in an unreasonable and unexplained delay in prosecuting its patent application and Apple Inc. (“Apple”) had suffered prejudice form the delay. PMC sued Apple in 2015alleging Apple’s digital rights management technology, Fair Play, infringed claims of the ’091 patent. After a jury awarded PMC over $308 million in damages for Apple’s patent infringement, the district court threw out the award based on finding the ’091 patent unenforceable.

Prosecution laches requires: (1) the patentee’s delay in prosecution must be unreasonable and inexcusable under the totality of circumstances and (2) the accused infringer must have suffered prejudice attributable to the delay. PMC appealed the district court’s findings with respect to both elements.

As to the first element, the CAFC found no clear error in the district court’s finding an unreasonable and inexcusable delay by PMC. PMC had an agreement with the Patent Office to prioritize certain of its patent applications over others. After the Patent Office rejected a claim with the key encryption and decryption limitations, PMC amended one of its non-prioritized applications to include the claim. PMC waited until 2003, sixteen years after the priority date of the ’091 patent, to include the key encryption and decryption limitations in an amended claim in a prioritized application. The PTO ultimately rejected the amended claim. However, in April 2011, while PMC was in pre-suit negotiations with Apple, PMC reintroduced the rejected claim to a non-prioritized application which subsequently issued as the asserted ’091 patent. Notably, the CAFC pointed out that PMC’s “compliance” with the agreement supports, rather than refutes, a finding of unreasonable and inexcusable delay, emphasizing that it was the way PMC prosecuted its patents, not the PTO, who caused the delay.

As to the second element, the CAFC found no clear error in the district court’s determination that Apple was prejudiced by the delay. PMC engaged in conduct causing delays at least through 2011, when it re-filed the previously-rejected decryption claim while it was negotiating with Apple, causing Apple to suffer injury. Even if PMC’s delay ended by 2003, the CAFC reasoned, PMC still prejudiced Apple because Apple “invested in or worked on” the Fair Play technology before 2003.

The CAFC here shows that prosecution laches, a rarely successful equitable defense, is still alive and well. Although the factual circumstances that would lead to a successful plea of this defense might be rare and extreme, patent practitioners should take note of the potential significant and fatal impact in litigation of delays that occurred in prosecution.

On January 12, 2023, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“TTAB”) redesignated a decision as precedential, in which it denied a trademark based on nonuse because the Applicant applied using the TEAS Plus application under the category of “musical instruments,” but sought to expand this identification category to “musical accessories” with an amendment to the application.

More specifically, Win-D-Fender (“Applicant”) applied for a federal trademark in “En-D-Fender” based on its use in commerce within International Class 15—“musical instruments.” Fender, a guitar manufacturer, who already has a registered trademark in “Fender” for “musical instruments” in International Class 15, filed a notice of opposition to registration of the mark on the grounds of nonuse, likelihood of confusion, and dilution by blurring. Applicant then sought to amend its identification of goods from “musical instruments” to “musical instrument accessories.”

When using the TEAS application (trademark electronic application system), only the goods and/or services listed in the proper identification ID field will be considered part of the identification. The instructions noted that if the ID Manual does not contain an accurate listing for the goods, an applicant must use the TEAS Standard filing option, which is $100 more than the Plus application, to create his own ID using his own words. However, the TEAS Plus application did not contain a “musical accessories” category. Instead, Applicant, using the cheaper TEAS Plus application, chose the “musical instruments” category and submitted a miscellaneous statement explaining that the correct category was “For Musical Instrument Accessories namely a wind guard mounted to a flute.”

The Board found that although an applicant can limit its identification of goods after filing, the Applicant’s proposed amendment expanded the scope of the original identification since, by definition, an “accessory” is not an “instrument.” Thus, the Board rejected Applicant’s motion to amend its identification of goods, found that Applicant should have used the TEAS Standard application which would have allowed the input of the correct category of “musical accessories,” and determined that due to the incorrectly identified category, there was no use of the mark “En-D-Fender” in commerce. Applicant will now have to file a TEAS Standard application and reincur the costs of the application and the time waiting for an approval.

Notably, the trademark application was filed by the managing director of Win-D-Fender, not an attorney experienced in trademark prosecution. This serves as a warning to those seeking to obtain trademark registrations: it is best to have an experienced attorney review the application prior to filing.

The Ninth Circuit recently affirmed the denial of the United States’ second motion for preliminary order of forfeiture of the Mongol Nation’s trademarks. The Ninth Circuit held that the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act (RICO) did not provide the government with the power to strip a group of their right to enforce their trademarks without transferring title to the government. The Mongol Nation is an unincorporated association comprised of members of the Mongols motorcycle gang. Over the past several years, the Mongol Nation applied for and obtained three registrations for collective membership marks.

Since 2008, the government prosecuted more than 70 members of the Mongol Nation under RICO and other criminal statutes for violent and drug trafficking related crimes. In relation with those crimes, the government also prosecuted the Mongol Nation for substantive RICO and RICO conspiracy crimes, and a jury convicted the Mongol Nation of those charges. The jury found that various property of the Mongol Nation, including the Mongol Nation trademarks, was forfeitable under the RICO conspiracy count. However, the district court denied such forfeiture, holding that it would violate the First and Eighth Amendments. The district court also concluded that the transfer of trademarks may not be legally possible under trademark principles. The government filed a second forfeiture application for the marks, requesting that defendant’s title to the trademarks be extinguished without transferring or vesting the trademarks with the United States, but the district court denied that application on the same grounds as its first denial. The Mongol Nation appealed the conviction, and the government appealed the second denial of forfeiture of the Mongol Nation trademarks.

The Ninth Circuit affirmed the Mongol Nation’s conviction and the second denial of the forfeiture of the Mongol Nation trademarks. The Ninth Circuit concluded that the plain text of RICO rendered the government’s application a legal impossibility, and as such there was no need to decide whether the forfeiture of the trademark violated any constitutional provisions. The RICO statute provides that “all right, title, and interest in property [forfeitable under RICO] vests in the United States upon the commission of the act giving rise to forfeiture under this section.” 18 U.S.C. § 1963(c). The government’s contemplated method of forfeiture in its second forfeiture application (to extinguish the Defendant’s title but not vest those trademarks with the government) was crafted to avoid constitutional issues but as a result was facially inconsistent with RICO’s forfeiture provision: RICO required the trademarks be vested. As such, RICO provided no mechanism for forfeiture to occur without a transfer of title to the government. This case demonstrates a rare intersection of trademark law and criminal law. The Ninth Circuit’s decision leaves open the constitutional questions of whether a properly crafted forfeiture notice on trademarks would run afoul of free expression or the prohibition on excessive fines.

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) recently reversed and remanded the Western District of Wisconsin’s summary judgment holding of invalidity for 12 patents belonging to Plastipak Packaging, Inc. (“Plastipak”) in an infringement action it brought against Premium Waters, Inc. (“Premium Waters”). The CAFC based its decision on a finding a genuine material dispute as to the invalidity theory adopted by the lower court, non-joinder of an inventor under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(f).

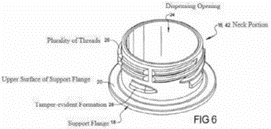

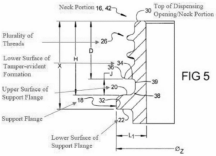

This case dealt with plastic disposable water bottles, like those sold in grocery stores and vending machines. Plastipak’s patents-at-issue particularly dealt with technology for the “Tamper Evident Formation” (“TEF”) that indicates whether the bottle cap has been opened. Premium Waters argued that two TEF features—a discontinuous TEF (see FIG 6) and the “X-Dimension” (see FIG 5) —were invented by Alessandro Falzoni, a third-party designer not named as a co-inventor on any of the patents.

The pre-AIA version of 35 U.S.C. § 102(f) bars a patentee when “he did not himself invent the subject matter sought to be patented.” An inventor is anyone who contributed in some significant manner to the conception or reduction to practice of the invention and not merely an explanation the current state of the art or well-known concepts. Pannu v. Iolab Corp., 155 F.3d 1344, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 1998). Failure to name the co-inventor of even a single claim may invalidate an entire patent for non-joinder. Id at 1348-49. That said, and although not addressed here, a patent owner may be entitled to save the validity of its patent by petition to the Director of the USPTO or by judicial decree per 35 U.S.C. § 256. Unlike inequitable conduct claims, invalidity by non-joinder does not require an intent to deceive.

The CAFC weighed the evidence presented by the parties including correspondence and testimony from Falzoni, testimony of named inventors, and prior art references shown as evidence of what a POSA would have known at the time of patenting. Although the CAFC found Premium Waters’ evidence that Falzoni was indeed a non-joined co-inventor was compelling, it did not negate the evidence presented by Premium Waters, which was sufficient to evoke skepticism and create a material dispute of fact. Thus, summary judgment was inappropriate and the CAFC reversed and remanded.

Generally, the law has trended away from extinguishing patent rights for problems with inventorship since the AIA. But the CAFC’s treatment of non-joinder in this case leaves some aspects of the law undecided, such as whether today’s § 256 would allow Plastipak to correct inventorship or whether the inventorship requirement allows for a post-AIA patent to be similarly invalidated. Patent challengers should have hope in this theory, and patent owners should be advised to properly list or correct inventorship of their patents.

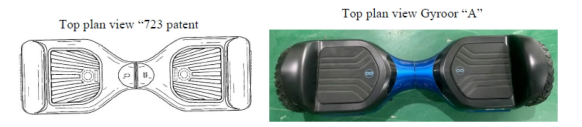

The United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois recently denied a renewed motion for a preliminary injunction seeking to prohibit sales of Defendants’ hoverboards that allegedly infringed Plaintiffs’ design patents (exemplary comparison pictured below):

The renewed motion came after the Court had previously issued a preliminary injunction, but the injunction was vacated by the Federal Circuit. The Court found that the patentee had failed to establish a sufficient likelihood of success on the merits, stating that “a reasonable jury could find that the accused products are not substantially similar to the patents in suit, such that an ordinary observer would not be deceived into believing that the accused products are the same as the patented design.”

In making its decision, the Court relied heavily on the Defendants’ expert’s opinion, a prior design patent examiner of 32 years, stating that the expert “conducted the proper analysis,” while simultaneously rejecting the Plaintiffs’ expert’s analysis. The Court reasoned that the Plaintiffs’ expert “failed to conduct an analysis of whether features [shared by both patents in suit and accused products] are substantially similar in the manner of their design, which is where the ‘focus’ of the analysis must be.” And because certain features, like shape, were similar across the prior art, the patents in suit, and the accused products, the Court found that “the overall impression is embodied in the details” and “it is impossible to consider a design’s overall impression without examining its details.” The Court found that the Plaintiffs’ expert “ignore[d] the details,” and that his analysis would “fail to gain a proper perspective on the overall impression of [the] design.”

Importantly, the Defendants’ expert and the Court pointed out numerous design differences between the claimed invention and the accused product, including the shape and extension of the wheel covers, the texture of the ribs on foot pads, the orientation of the LED lights, and branding text present on the accused products. Further, the Court agreed with the Defendants’ expert that because the patent claimed the bottom side of the hoverboard, any differences between the bottoms, which are not normally visible, must also be considered for infringement. These differences included vent holes, angles, and slopes.

In sum, the Court found that the Plaintiffs failed to carry their burden of showing a likelihood of success on the merits based on differences Plaintiffs claimed to be minor and not sufficiently centered on an “overall visual impression.” While the Court’s finding is not dispositive on the issue of infringement, it is unlikely that the Court’s focus on the “details” will shift in a field with crowded prior art.

Irwin IP LLC was founded by Barry Irwin in 2014. Since its founding, Irwin IP has developed a thriving intellectual property litigation practice. Irwin IP is pleased to announce that, effective January 1, 2023, it will be converting to a partnership, and that Lisa Holubar, Mike Bregenzer, and Jason Keener will be joining Barry as partners. Both Lisa and Mike were previously partners, with Barry, at the top ranked AmLaw 100 law firm.

Lisa has been with Irwin IP since its establishment, and she leads the firm’s Trademark and Advertising Litigation practice. In addition to her extensive litigation experience, Lisa counsels clients on all aspects of selecting, protecting, and enforcing their trademarks. Lisa also aids clients in connection with various related matters including UDRP arbitration and website and advertising review.

Mike’s relationship with Irwin IP started about the same time as Lisa’s when, as General Counsel for Ranir—a manufacturer of medical devices and OTC pharmaceuticals— he retained Irwin IP to handle a bet-the-company IP litigation against Proctor & Gamble. After retaining Irwin IP on several additional IP litigation matters, and after Ranir’s acquisition by publicly traded Perrigo, Mike joined Irwin IP in 2020 as a Senior Attorney. Since then, Mike has been managing a significant portion of the firm’s patent litigation business.

Jason joined Irwin IP a year ago as a Senior Attorney, proving quickly that he is a fantastic attorney and rapidly becoming a firm leader. In addition to bringing his broad ranging intellectual property litigation experience to the firm’s existing clients, he has also brought with him and has continued to attract a range of clients across the IP litigation landscape.

“I am extremely proud to see Irwin IP take this next step and to partner with Lisa, Mike, and Jason. They are all fantastic attorneys and have contributed substantially in the growth of Irwin IP,” Barry Irwin commented regarding their elevation to partner. “I look forward to seeing how the firm continues to grow and prosper with their leadership.”

Irwin IP concentrates on mission-critical, high-profile intellectual property and technology-related litigation. Our clients range from Fortune 500 companies to pioneering startups. We have enforced intellectual property portfolios protecting product lines generating hundreds of millions of dollars annually. We have also cleared the way for our clients to sell such product lines. We routinely, successfully litigate against the largest, most prestigious law firms representing the largest companies in the world on matters valued in the tens and hundreds of millions.

Barry has been litigating mission-critical, high-profile intellectual property and technology matters in federal courts across the country for nearly 30 years. In addition to his active litigation practice, Barry has been an Adjunct Professor at Notre Dame Law School for nearly a decade, where he teaches both Patent Litigation and Entertainment Law. Barry is also the Board President of Lawyers for the Creative Arts, a former executive board member of the Linn Inn American Inn of Court, and long-term member of the Village of Burr Ridge Planning Commission and Zoning Board of Appeals.

Barry was just recently named by Best Lawyers® as the 2023 “Lawyer of the Year” for both “Litigation – Patent” and “Copyright Law” in Chicago, an honor bestowed on just a single lawyer in each practice area and designated metropolitan area. In 2018, Barry was selected by Thomson Reuters as one of the Top 100 lawyers in Illinois as part of its Super Lawyers selection process, one of only eight intellectual property attorneys on the list, and the only one from a small (under 75 attorney) intellectual property boutique. And, each year, for nearly twenty years, Barry has been named a Leading Lawyer and a Super Lawyer. Barry also received Martindale Hubbell’s highest ratings (AV, AV+ and AV Preeminent) in his first years of eligibility and each year thereafter.

Learn more about our practice at https://irwinip.com/our-practice/

All firm email and phone numbers remain the same, as well as our location of 150 N Wacker.

On November 17, 2022, the District of Delaware adjudicated a perfect storm of international patent enforcement: a method claim infringement dispute between an Australian patent owner (F45) and the U.S. subsidiary (BFT) of another foreign company (BFT Australia) where some steps were performed in Australia, and others by BFT’s U.S. franchisees. The Court held the asserted patent invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101. This allowed the Court to bypass the case’s complex infringement posture. But Judge Bryson, serving as a Visiting Judge in the District of Delaware, was not one to skip a station.

F45 Training Pty Ltd. (“F45”) owns U.S. Patent No. 10,143,890 (the ’890 Patent). Simplified, the ’890 Patent calls for a library of workout programs tailored to a given fitness studio to be stored on a server and provided to the studio, and for each program to contain both instructions to the studio specifying how workout equipment should be rearranged for that session, and instructions to be played on screens on the workout equipment to coach gym goers through the session. In classic Internet-enabled patent fashion, claims 1-2 covered the server-side of the system, and claims 3,4, and 6 covered the studio-side.

The ’890 Patent escaped invalidation at the pleadings stage where then-District Court Judge Leonard Stark found that the claims were directed to an abstract idea but could not then determine whether the claims individually or as an ordered combination contained an “inventive concept.” Thus, on summary judgment, Alice was the Court’s first port of call, and it agreed that “providing directions for exercises and varying exercise program” were “clearly abstract ideas.” For Step Two, F45 argued that varying workouts to create a “surprise element” for gym-goers was unconventional and provided the inventive concept. However, the claim covered any variation in the exercise programs and not just surprising variations. The claimed “fitness library” of pre-programmed exercise routines also did not provide an inventive concept because it merely replaced a fitness instructor. Thus, the Court held the ’890 Patent invalid under § 101.

And then things got interesting. As to claims 1 and 2, which implicated the interaction between the US-based studios and BFT’s Australia-based server and staff, BFT argued that it did not infringe the claimed method because some steps were performed outside the United States. F45 argued that BFT could still infringe because it “sold” or “offered to sell” the method in the United States to its franchisees. To support this theory, F45 relied upon NTP, Inc. v. Research in Motion, Ltd., 418 F.3d 1282 (Fed. Cir. 2005) to argue that the Federal Circuit had left open the question of whether a method patent could be infringed by “sale” or an “offer for sale” under 35 U.S.C. § 271(a). However, as the Court observed, although NTP did not categorically foreclose infringing a patented method via “sale”, it held that RIM’s performance of steps of a patented method as a service for its customers could not be a sale or offer for sale. Finding BFT’s actions factually analogous to RIM’s in NTP, the Court found no infringement of the server claims.

As to the studio-focused claims, contributory infringement was a non-starter because it required “sale of a product of some sort,” and the provision by BFT to franchisees of staple articles like computer and networking components did not suffice. But, as to inducement, there were factual issues regarding direct infringement, intent, and aiding and abetting that created a genuine issue of material fact.