In a landmark decision affirming longstanding principles of trademark law, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Lanham Act’s names clause does not violate the First Amendment, confirming the authority of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) to regulate trademarks containing living individuals’ names without their consent. In Vidal v. Elster, the Supreme Court reversed a Federal Circuit decision that had found the names clause violated the First Amendment. The Federal Circuit had ruled that, as a viewpoint-neutral, content-based restriction on speech, the names clause did not serve a significant government interest and thus failed to meet the requirements of intermediate scrutiny.

The dispute originated from Steve Elster’s application to trademark “Trump Too Small,” which refers to an exchange during a 2016 debate between then-presidential candidate Donald Trump and Senator Marco Rubio. The PTO rejected that application on the basis that it violated the Lanham Act’s name clause, which prohibits the registration of a trademark that “consists of or comprises a name . . . identifying a particular living individual except by his written consent.” Elster argued that the PTO’s refusal infringed upon his First Amendment right to free speech, but the PTO upheld the denial. The Federal Circuit reversed, and the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

In reversing the Federal Circuit, the Supreme Court focused on the differences between content-based and viewpoint-neutral regulations of speech. The Court acknowledged that while the names clause is content-based because it targets trademarks that include a person’s name, it is not viewpoint-based since it does not consider the opinion or message behind the use of the name. Thus, the names clause does not target any specific viewpoint but uniformly prohibits the use of living individuals’ names without consent, regardless of the context.

The majority opinion supported by six justices (there were three concurring opinions) emphasized that the names clause serves a fundamental purpose in trademark law: ensuring that consumers can accurately identify the source of goods and services, thereby preventing confusion and protecting the goodwill associated with a person’s name. By prohibiting the registration of trademarks containing living individuals’ names without consent, the names clause maintains the integrity of the trademark system and safeguards personal reputations. In support, the majority cited historical and traditional underpinnings of trademark law, highlighting that trademark restrictions based on content have coexisted with the First Amendment for over a century without raising constitutional concerns. Early American and English trademark law consistently prohibited the use of another person’s name to avoid consumer confusion and protect the individual’s reputation. This historical context, the majority argued, justified the content-based nature of the names clause, distinguishing it from viewpoint-based restrictions the Court has found unconstitutional.

This decision confirms that the PTO has the authority to regulate trademarks that include names and provides clearer guidelines for assessing if content-based but viewpoint-neutral trademark restrictions are constitutional. However, the Court noted that this decision does not establish a complete set of rules for all content-based trademark restrictions and does not imply that similar history and tradition are needed to support every content-based trademark restriction. As a result, parties seeking trademarks that could potentially test the application of those content-based restrictions should carefully weigh the First Amendment’s scope and how the potential trademark fits within that scope when considering strategy for registration. And importantly, while Elster can still produce and sell shirts that say, “Trump Too Small,” he cannot trademark the phrase in order to stop others from also selling such merchandise.

In October of 2021, pursuant to the triennial review process of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DCMA”), the Library of Congress (the “Library”) promulgated rules exempting certain classes of copyrighted works, e.g., medical software in devices like CT scanners and MRI machines, from anti-circumvention provisions of the DCMA. Thereafter, two medical trade associations filed suit, arguing that the exemption for repair of medical devices must be declared to be unlawful and void, and any enforcement of it enjoined, pursuant to the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”). This case helps to clarify whether opponents to the right to repair can use judicial review under APA to challenge future DMCA exemptions.

The DMCA prohibits circumvention of technological protections that limit access to digital copyrighted material to prevent piracy and unlawful reproduction. Because such measures can frustrate fair use by third parties, Congress has authorized that every three years, the Library is to identify classes of copyrighted works that should be exempt from the DCMA’s anti-circumvention provision. The process: one can apply to the Library for an exemption, a public comment period follows, the Copyright Office makes recommendations, then the Library issues rules. Prompted by independent service operators who argued they could not perform maintenance or repairs on certain medical devices, the Library allowed an exemption to the DCMA’s anti-circumvention provision to address medical device software.

Here, the District Court for the District of Columbia held, in part, that such claims were barred by sovereign immunity because the Library was part of “Congress” and not an agency subject to review under the APA. On Appeal, the Court disagreed, stating that the “agency” question missed the point. Instead, reading Sections 701(e) and 702 of the Copyright Act together with the DMCA, the Court concluded that DCMA rules, like other copyright rules, are indeed subject to APA review, which provides waiver of sovereign immunity. The Court concluded that the Copyright Act stated that “all actions” of the Register of Copyrights under Title 17 – which consists of rules that must be approved by the Librarian – are subject to the APA. The Court also mentioned that there was no “indication in the DMCA that Congress, having allocated this substantial regulatory power to the Librarian and Register,” would go unchecked by judicial review. As such, the Court noted that Congress does provide for APA review of the DMCA regulations by statue despite whether the Library is an agency and the fact that the DMCA is silent with respect to judicial review. The Court vacated and remanded, directing the lower court to address the APA claims.

Proponents of the right to repair medical devices may see this case as a setback: a way for medical devices makers to increase profits without concern that such restrictions may delay the repair of medical equipment and result in patient harm. Opponents may see this case as a victory: a way to ensure patient safety by allowing only approved repairers/repairs. Regardless, this case does not address the substance of the issue as it merely provides for APA review of DCMA exemptions. Both proponents and opponents will want to follow the remanded action, where the exemptions themselves will be examined.

A Washington jury recently issued a $72 million verdict in favor of Zunum Aero Inc. (“Zunum”), a now-defunct aerospace startup, against The Boeing Company (“Boeing”) for willful and malicious misappropriation of trade secrets, breach of a nondisclosure agreement (“NDA”), and tortious interference. The companies had multiple NDAs, and Boeing argued its use was actually permitted by those NDAs. The jury, however, disagreed, highlighting the difficulties in maintaining ongoing obligations when obtaining proprietary information.

Zunum developed proprietary methods for a 9-12 seat hybrid-electric (“HE”) aircraft that could be viable by the early 2020s, a decade prior than previously believed feasible by those in the industry, including Boeing. Pursuant to a 2016 NDA, Zunum disclosed to Boeing confidential information about the HE project. Boeing was permitted to use Zunum’s information to “explore the feasibility of potential projects in the field of electric based power systems for aviation use.”

In 2017, the parties executed a second NDA, and Boeing invested $5 million in Zunum. Zunum continued to share proprietary information which Boeing was only permitted to use for purposes of managing its investment in Zunum.

Boeing then launched internal R&D efforts in the HE aircraft area. Zunum put forth evidence that Boeing used Zunum’s information in these R&D efforts. Zunum also pointed to Boeing communications that the Zunum investment allowed Boeing to quickly “catch up” with the state of technology. It also came out that Boeing placed individuals who received Zunum information on its R&D team.

The jury found for Zunum on trade secrets misappropriation, breach of an NDA, and a tortious interference claim, further finding Boeing’s actions willful and malicious. This case highlights the importance of making joint development arrangements clear. Boeing’s defense, that the use was permitted by the parties’ NDAs, was rejected not only by the court on summary judgment but also by the jury.

This case also shows the importance of implementing internal mitigation strategies. Boeing’s defense may have been more successful if they could have pointed to efforts to conduct its internal R&D independently from Zunum’s information, to sequester employees who received proprietary information, or to prevent any reliance on the internal R&D after it ended. At a minimum, such steps may have convinced a jury that any misappropriation was not willful or malicious.

Irwin IP is proud to announce Victoria Hanson successfully graduated from the 2024 Chicago Bar Association Leadership Institute, a program aimed at fostering leadership skills and professional relationships among emerging legal professionals. Victoria’s completion of this program spotlights her commitment to professionalism and dedication to Chicago’s legal community. The program featured sessions covering a range of topics including foundational leadership principles and advanced business development techniques.

Congratulations on this accomplishment, Victoria!

——–

Irwin IP specializes in mission-critical intellectual property and technology litigation, catering to a diverse client base, including Fortune 500 companies and innovative startups. Our expertise extends to enforcing and protecting intellectual property portfolios, ensuring our clients’ product lines, worth hundreds of millions annually, remain secure. Notably, we routinely, successfully litigate against the largest, most prestigious law firms representing the largest companies in the world on matters valued in the tens and hundreds of millions.

Much has been discussed about the underrepresentation of Asian American attorneys in top legal jobs. The Illinois Supreme Court Commission on Professionalism asked Asian American lawyers and law students in how law firms can better support them, what has been crucial to their success, and how legal organizations can aid their career development. One of our associates, Suet Lee, shared her thoughts.

On May 1, the Federal Circuit reversed a district court’s dismissal of Intellectual Tech’s (“IT’s”) patent infringement claims against Zebra Technologies (“Zebra”) for lack of constitutional standing. The Federal Circuit found that even though IT defaulted on a loan, which gave their bank rights to the patents used as loan security, IT still had standing to sue, and the default did not automatically strip IT of its rights to the patents. When using patents as loan security, patent owners should be weary of provisions that automatically assign the patents to the bank in the event of default as doing so may jeopardize their standing to enforce the patents.

In this case, IT entered into a loan agreement that gave the lending bank a security interest in IT’s patents. The loan agreement provided that if IT defaulted, the bank may “at its option” sell, assign, transfer, pledge, encumber, dispose of, enforce, and license the patents to any third party. IT defaulted on the loan, but the bank never exercised any of its options to the patents.

IT asserted the patents against Zebra in the Western District of Texas. Zebra moved to dismiss IT’s claims for lack of constitutional standing. Constitutional standing requires (1) an injury in fact, (2) traceability, and (3) redressability. Here, injury in fact was the only disputed factor. The district court granted Zebra’s motion because in its view the fact that Zebra could have obtained a license to the patent from the bank deprived IT of its exclusionary rights.

The Federal Circuit reversed, explaining that IT only needed to show that it retained at least one exclusionary right to satisfy the injury in fact requirement by showing an invasion of a legally protected interest. The Federal Circuit further explained that the district court incorrectly concluded that the bank’s option to assign the patents divested IT of its legal interest in the patents. In fact, nothing in the loan agreement indicated that the mere triggering of the bank’s optional rights automatically deprived IT of all rights to the patents. Even though the bank had the non-exclusive ability to license the patents, IT still retained the exclusionary right to sue unlicensed infringers, and thus satisfied the injury in fact requirement for constitutional standing despite defaulting.

Presumably, if the bank had exercised any of its optional rights, then IT may have lost its standing to sue. Moreover, Zebra could have attempted to avoid infringement by asking the bank to exercise its optional rights to grant it a license or assignment. Ultimately, default provisions that require the bank to proactively exercise an option to possess the patent are more beneficial to the patent owner. However, even optional provisions open the door for an accused infringer to avoid liability by approaching the bank for a license or assignment if the patent owner defaults. Thus, patent owners should be cautious when using patents as loan security and be aware of default provisions that may affect their standing to enforce the patents. Patent owners may also consider granting lenders rights to litigation or licensing proceeds generated by the patents as loan security, instead of ownership rights, to avoid the potential constitutional standing issue.

Irwin IP is delighted to welcome our 2024 summer associates, Katherine O’Malley and Faye Vasilopoulos. Their impressive academic achievements and diverse experiences make them valuable additions to our firm.

Katherine is a third-year student at Loyola University Chicago School of Law, where she serves as Senior Editor of the Journal of Regulatory Compliance. Her experience includes working as a judicial extern in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. Katherine is actively involved in Loyola’s Intellectual Property Law Society and has contributed as an Associate Editor of the Annals of Health Law and Life Sciences. She holds a Bachelor of Science in Environmental Studies with a concentration in Law and Policy from Santa Clara University.

Faye is a third-year student at the University of Illinois Chicago School of Law, where she is the Editor-in-Chief of the UIC Law Review. Her dedication to the field of law is further demonstrated by her recognition as the recipient of the 2023 Hellenic Bar Association legal scholarship. Faye earned her Bachelor of Science in Biology from Elmhurst University, where she conducted significant research on stroke prevention.

Our summer associates will work alongside our attorneys and participate in meaningful projects. We are dedicated to supporting their growth, creating an environment that nurtures their professional development, and learning to practice law according to our values of innovation, integrity, and impact. By the end of the program, they will have gained invaluable real-world experience and created lasting memories.

Let’s make this summer truly impactful!

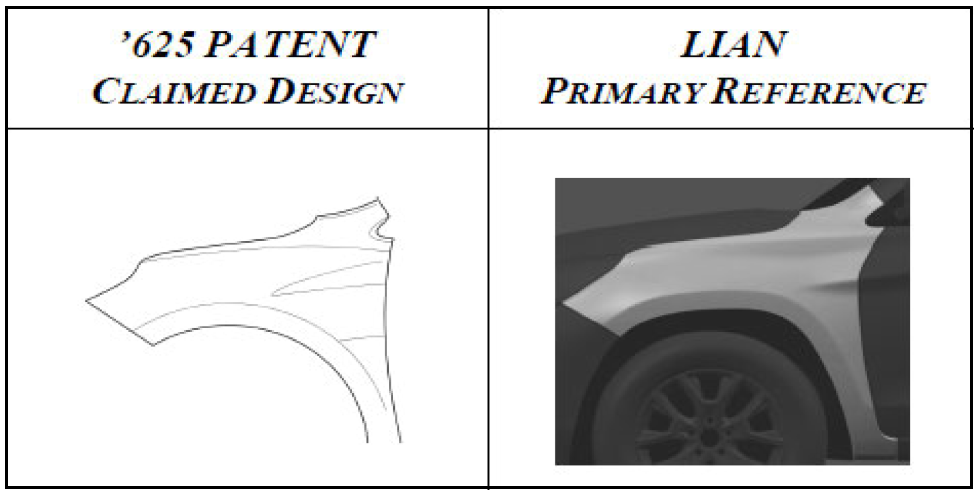

On May 21, 2024, the Federal Circuit overruled its long-standing Rosen-Durling obviousness test for design patents and replaced it with the more flexible four-factor Graham1 test. LKQ filed2 a petition for inter partes review of GM Global Technology Operations LLC’s U.S. Design Patent D797,625 (the “D’625 Patent”), asserting the D’625 Patent was invalid as obvious under 35 U.S.C. § 103. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board applied the Rosen-Durling test and found that the prior art did not render the D’625 Patent obvious. On appeal, a panel of the Federal Circuit affirmed, rejecting LKQ’s argument that the Supreme Court’s decision in KSR International Co. v. Teleflex, Inc. overruled Rosen-Durling. KSR established a more lenient test for assessing obviousness in utility patents that LKQ asserted overruled the rigid two-part Rosen-Durling test.

For the first time in fifteen years, the Federal Circuit granted rehearing en banc in a design patent case to assess the merits of Rosen-Durling. The en banc court unanimously held in favor of LKQ, finding Rosen-Durling to be too rigid an unreconcilable with Supreme Court precedent and 35 U.S.C. § 103: “invalidity based on obviousness of a patented design is determined based on factual criteria similar to those that have been developed as analytical tools for reviewing the validity of a utility patent under § 103, that is, on application of the Graham factors.”

The court then delineated the four-part Graham test as it applies to design patents. The first factor—the scope and content of the prior art—applies the analogous art standard to all prior art references, replacing the “basically the same” and “so related” standards. However, a primary reference still must be determined in this factor to prevent hindsight bias. With utility patents, whether art is analogous depends on (1) whether the art is from the same filed of endeavor as the claimed invention; and (2) if the art is not in the same field of endeavor, whether the reference still is reasonably pertinent to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved. The court noted that the first part of this standard applies readily to design patents, but the second part does not. It declined to “delineate the full and precise contours of the analogous art test for design patents,” holding that “[p]rior art designs for the same field of endeavor as the article of manufacture will be analogous, and we do not foreclose that other art could also be analogous,” leaving further development of the standard to future cases.

The remaining Graham factors mirror utility patent law. The second factor compares the visual appearance of the claimed design and the prior art to determine the differences between them. The third factor requires determining characteristics of a designer of ordinary skill in the art because an obviousness determination is from that designer’s viewpoint. The fourth and final factor requires determining “whether an ordinary designer in the field to which the claimed design pertains would have been motivated to modify the prior art design ‘to create the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design;’” if answered in the affirmative, the design is obvious.

The court did not “disturb [its] existing precedent regarding … secondary considerations such as commercial success, industry praise, and copying,” but noted uncertainty in the application of other secondary considerations—such as long felt but unresolved needs and failure of others—but, again, left these questions for future cases.

Briefly addressing concerns of overruling the Rosen-Durling test, the court noted that the Graham test has years of precedent that courts can draw on for assessing obviousness in the design patent. Though much of the test is a case-by-case factual analysis, the difficulties presented thereby are not unusual. This decision marks a significant change in how design patent obviousness analyses are conducted. The adoption of the flexible Graham test in design patent cases is likely to lead to more design patents being rejected at the USPTO (as noted in a previous IP Case of the Week, under Rosen-Durling, 102/103 rejection rates during design patent prosecution were “about 4%” compared to nearly 70% for utility patents) and could potentially lead to longer trials with a higher success rate for defendants as design patent invalidity defenses will likely be more difficult to summarily dismiss.

- Graham v. John Deere Co., 383 U.S. 1 (1966). ↩︎

- Disclaimer: Irwin IP LLP is privileged to be lead counsel for LKQ Corporation and Keystone Automotive Industries, Inc. in several design patent infringement matters, including this case against GM Global Technology Operations and by extension General Motor ↩︎

On May 21, 2024, the Federal Circuit issued an en banc decision in our client LKQ Corp.’s case against GM Global Technology Operations LLC, overturning the long-standing obviousness test for design patents.. The court ruled that the obviousness test for design patents should align with the test for utility patents, marking a significant shift in design patent law.

The law for design patent obviousness may change soon following the Federal Circuit Court’s decision on our client LKQ Corp.’s victorious case against GM Global Technology Operations LLC.