The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) recently upheld a decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) that found some claims of U.S. Patent 8,815,830 (“the ’830 patent”) unpatentable as anticipated. The ’830 patent’s owner, the Regents of the University of Minnesota (“Minnesota”), argued before the PTAB that the petition for inter partes review filed by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (“Gilead”) relied on a prior art reference that did not have priority over the ’830 patent. But the PTAB found that the ’830 patent’s priority claim to a sequence of patent applications that stretched back almost 20 years (the “priority applications”) lacked a written description sufficient to support the claim. Minnesota appealed the PTAB’s decision.

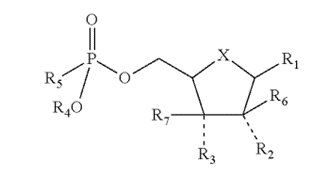

The ’830 patent was directed towards drugs that inhibit viral reproduction and the growth of cancerous tumors when they are metabolized by the human body. The first claim of the ’830 patent was a broad genus claim that covered many of these types of chemicals with the same general structure (shown right) including sofosbuvir, a drug developed by petitioner Gilead to treat hepatitis C infections.

Minnesota’s argument on appeal centered on the PTAB’s determination that the priority applications, in the broad outlines of their specifications, did not contain written description of chemicals claimed by the ’830 patent. In order to support a patent’s claim of priority and receive the benefit of an earlier filing date, an earlier patent application must “constitute a full, clear, concise and exact description” to a person having ordinary skill in the art. In re Wertheim, 646 F.2d 527, 538–39 (CCPA 1981). As in Fujikawa v. Wattanasin, an ipsis verbis, or literal prior disclosure is not required in every instance if a prior disclosure provides clear clues that “blaze a trail through the forest” and would lead an ordinarily skilled person precisely to a particular “tree” (technology) known as “blaze marks.” 93 F.3d 1559, 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1996).

The CAFC found that Minnesota had proposed a “maze-like” written description involving a littany of possibilities and alternate chemical paths with no indication as to what a skilled artisan would do beyond pure experimentation when they came to each branching path. This ruled out ipsis verbis written description disclosure, and the CAFC also found that Minnesota could not claim that these confusing proposals were blaze marks either, as the priority applications failed to point to the disclosure made in the prior art. The CAFC agreed that the priority applications, with enough roundabout steps through different chemical subgenera, would eventually lead to to the ’830 patent’s claims. But, they did not show structural features of the genus that would enable a skilled artistan to “visualize or recognize members of the genus” that were disclosed in the prior art. Ariad Pharms., Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336, 1350−52 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

Here, the CAFC reaffirmed that, in order to receive the benefits of an earlier-filed priority application, the priority application must particularly disclose the invention at issue—creative attorney argument attempting to link up the priority application with the claims of the patent will not suffice.

This week, the Fourth Circuit affirmed the United States Trademark Trial and Appeal Board’s (“TTAB”) and subsequent Eastern District of Virginia’s (“District Court”) summary judgment finding that “GRUYERE” could not be registered as a certification mark because the term had become generic. Specifically, “GRUYERE” is generic because the “relevant consuming public” only viewed gruyere as a “firm, nutty flavored cheese that can be made anywhere.”

Appellants were Swiss and French consortiums that sought a certification mark which would limit use of the term “gruyere” in the United States to a cheese that could only be produced in the Gruyère region of Switzerland and France. Appellants pointed to the fact that gruyere cheese originated from the Gruyère region in 1115 AD and enjoyed “protected designations of origins” and “protected geographical indications” in Switzerland and France. Appellants also argued that other cheeses, like “Roquefort” and “Reggiano,” enjoy the benefits of a certification mark.

But the Fourth Circuit and previous courts disagreed, pointing to substantial evidence that “American purchasers” generally did not distinguish cheeses based on region, but based on the “type of cheese.” Specifically, the Fourth Circuit cited the FDA’s standard identity for “Gruyere cheese,” which defines gruyere as a cheese that contains “small holes or eyes,” “a mild flavor, due in part to the growth of the surface-curing agents,” that is aged a minimum of ninety days, and has a “maximum milkfat content [of] 45 percent by weight of the solids and [a] maximum moisture [of] 39 percent by weight.” The Fourth Circuit noted that the standard “does not contain any geographic restrictions on where the cheese can be produced.” Accordingly, the FDA’s standard identity was strong evidence that gruyere had become a generic term for the type of cheese. The Fourth Circuit also pointed to the “millions of pounds” of gruyere cheese produced in the midwestern United States and sold across nearly every retailer across the country. Although appellants wrote cease-and-desist letters to numerous retailers to try and stop those retailers from selling domestically produced gruyere cheese, most of those retailers declined to do so with no consequence. Accordingly, the Fourth Circuit reasoned that “the more members of the public see a term used by competitors in the field, the less likely they will be able to identify the term with one particular producer” or “geographic region.” Finally, the Fourth Circuit did not find the “Roquefort” and “Reggiano” certification mark comparisons convincing because the FDA standard of identity prescribed alternative names for those cheese. For example, Roquefort could be referred to as “blue-mold cheese.” Likewise, many domestic purchasers of “Reggiano” cheese likely refer to it as parmesan, a term originating from Parma, Italy that has undoubtedly become generic.

Like with trademarks, it is important for parties seeking a certification mark to begin education and enforcement on the applied-for marks early. The record in this case seems to indicate that the United States only started large scale production of domestic gruyere cheese in 1991. But appellants in this case applied for a certification mark in 2015. Appellants also sent cease-and-desist letters with little effect, demonstrating the importance of actually enforcing those cease-and-desist letters with known infringers. By 2015, American purchasers had already genericized gruyere as just another type of cheese.

Sticks and stones may break your bones, but don’t complain to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) if a patentee calls you an infringer, claims you copied, or threatens to sue your customers. Holding speech restrictions granted in a preliminary injunction were an abuse of discretion, the CAFC made clear that Lite-Netics’ ability to provide notice to an alleged infringer or describe its intent to enforce patent rights preempt state-law claims where the claims were not objectively baseless.

Lite-Netics, holder of two utility patents for magnetic holiday string lights, appealed the district court’s preliminary injunction barring Lite-Netics from suggesting competitor Holiday Bright Lights (“HBL”) is a patent infringer, copied Lite-Netics’ lights, or that HBL customers might be sued. In 2017 and April 2022, Lite-Netics sent cease-and-desist letters to HBL that asserted patent infringement. Then in May 2022, Lite-Netics communicated to its own customers (some of whom were also HBL’s) about alleged infringers in the market and its intent to enforce its patents. After Lite-Netics sued HBL in August 2022, it sent another letter that “any company using or reselling the HBL products” may be joined in its lawsuit against HBL. HBL counterclaimed, in part, that the second customer letter constituted defamation and tortious business interference under state law, moving for a TRO and preliminary injunction on those bases.

The district court issued a TRO and then a preliminary injunction against Lite-Netics. The district court determined that it did not see how Lite-Netics could reasonably believe that HBL’s magnetic cord infringes the patent, and the therefore, the claim that HBL infringes (literally or under the doctrine of equivalents) was therefore likely baseless. Vacating the injunction and remanding, the CAFC explained that notice of patent rights is an issue of federal law— “not a matter of state tort law”—unless bad faith is present. Bad faith, the CAFC said, involves First Amendment principles (where an injunction is severe) and is present only if asserted patent claims are objectively baseless. The CAFC then reviewed the patent claims and found an objectively reasonable basis for Lite-Netics’ infringement allegations; thus, there was no bad faith.

First, the CAFC found that “a magnet” is not limited to a one-piece magnet under patent law, and typical traps that might limit a patentee’s scope (e.g., what is shown in patent figures or included in specification language) are not at issue. Second, HBL’s two-piece magnet, according to the CAFC, may reasonably be determined to be equivalent to “a magnet” where a two-piece magnet achieves the same function in the same way to produce the same result. Third, on the meaning for the lights to be “attached”, the CAFC noted legal precedent supported Lite-Netics’ broader definition. Thus, the CAFC found that the district court had abused its discretion in concluding that Lite-Netics could not reasonably expect success on the merits.

As a practice pointer, unless advancing objectively baseless claims, patentees should be free to announce infringement claims without fear of liability for state law claims, like defamation or tortious interference.

Be careful of showing your claimed inventions at tradeshows. On February 15, 2023, the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) affirmed a summary judgment ruling that, by merely showcasing an embodying device at an industry event (the “Event”), Minerva Surgical, Inc. (“Minerva”) had engaged in an invalidating public use more than one year before its patent filing. Although Event attendees could not handle the device, the attendees were able to scrutinize the device and the claimed invention was ready for patenting based on prototypes, drawings, and a detailed description of the invention.

Minerva sued Hologic, Inc. and Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC (collectively “Hologic”) for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,186,208 (the “’208 Patent”) in the District of Delaware (“the district court”). The ’208 Patent is directed to surgical devices for a procedure which stops or reduces abnormal uterine bleeding. Hologic moved for summary judgment of invalidity arguing that the ’208 Patent was invalid under the Pre-AIA public use bar of 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) because Minerva demonstrated a device at the Event that disclosed the claimed invention of the ’208 Patent more than one year before the ’208 Patent’s priority date. The district court held the demonstration and display of Minerva’s device at the Event embodied the ’208 Patent. Minerva appealed arguing that: (1) the “mere display[]” of the device was not a public use; (2) the device did not embody claim 13 of the ’208 Patent; and (3) that the device was not “ready for patenting” at the time of the Event because Minerva was still improving the underlying technology.

Regarding Minerva’s arguments, the CAFC held that the nature and public access of the Event indicated a public use. The Event was known as the “Super Bowl” event of the industry, was open to the public, included attendees who were critical to Minerva’s growing business; 15 devices were used at the Event; and the devices were shown on multiple days. The CAFC found these demonstrations to be more than a “mere display” of the claimed invention because Minerva pitched its device to industry members who were allowed to “scrutinize” the device to “see how it operated.” Minerva argued that there was no evidence that their device could be handled at the Event, but the CAFC held that the public use bar is not predicated on physically holding the device. Additionally, the CAFC noted that Minerva imposed no confidentiality obligations on Event attendees and that Minerva did not follow its alleged policy not to disclose proprietary information before Minerva files for a patent.

Next, the CAFC held that Minerva’s device embodied claim 13 of the ’208 Patent. Minerva’s documentation before and after the Event express disclosed the limitations of claim 13. This documentation included, test studies, lab notebooks with CAD drawings, a presentation, a brochure, and a bill of materials.

Finally, the CAFC held Minerva’s invention was ready for patenting for two reasons. First, Minerva reduced the invention to practice by creating a “working prototype” that operated for its intended purpose. The CAFC held Minerva’s claims of improving the invention were merely “later refinements” or “fine tuning” and were enough to find the invention was ready for patenting. Second, the drawings and detailed descriptions in Minerva’s documents were enough for a person of ordinary skill to practice the invention. Therefore, the CAFC held the invention was ready for patenting and was an invalidating public use.

This decision serves as a cautionary tale for inventors looking to show off their inventions at industry events and tradeshows. Showing an invention at a public event, such as an industry-wide event, should be presumed to be a public use and the inventor or assignee should take care to file for patent protection within one year of any such event.

Two of Irwin IP’s 2022 Summer Associates, who will be joining as associates in the fall, Emad Mahou and Suet Lee, were invited to represent their law school in a summit presented by the Illinois Supreme Court on Access to Justice. They were privileged to meet Illinois Supreme Court Chief Justice Mary Jane Theis.

In a patent dispute between plaintiffs ChromaDex and Dartmouth College and defendant Elysium Health over spilled milk, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Delaware District Court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of the Elysium Health, based the subject matter of the asserted patent being patent-ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101. The plaintiffs appealed claiming that their patent on an isolated compound differs from the related, naturally occurring compound found in cow’s milk. Neither the District Court nor the Federal Circuit found this argument compelling–both courts explaining that the claims were directed to a natural phenomenon in violation of § 101, and that the alleged significant increase in “NAD+ biosynthesis” and higher concentration of the isolated compound, called “NR”, were not part of the claims.

Section 101 states that “[w]hoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.” However, the Supreme Court, citing Myriad Genetics, explained that laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable. In recent years, and particularly after the Supreme Court’s Alice decision, the Patent Office and District Courts across the country have rejected a large number of patents and applications relating to abstract ideas, such as computer-implemented business methods, under § 101. The Federal Circuit here, however, reconfirmed that § 101 is just as applicable to patents directed to natural phenomena.

The Federal Circuit explained that, as in Myriad Genetics, mere isolation of a compound that naturally exists is not sufficient, on its own, to confer patent eligibility. The court explained, quoting Chakrabarty, that a claimed composition must have “markedly different characteristics and have the potential for significant utility,” to be patent-eligible, and noted that the claimed isolated compound was “no different structurally or functionally from its natural counterpart in milk.” Notably, the broadest claim of the patent required a “combination” that is an admixture of any one or more of 23 different carriers, one of which was “a sugar”. Since “milk is an admixture containing a sugar (lactose),” the court found that the claims were only differentiated from milk due to the “isolated [NR]”. ChromaDex and Dartmouth argued that the isolation of the composition allows for significant increases of its desirable effects. The panel noted that although that may be true, the claims failed to actually include the purported advantages the plaintiffs relied on. The Federal Circuit further noted that in addition to the claims’ ineligibility as products of nature, they were also ineligible because they “lack[ed] an inventive step because they are directed to nothing more than the [same] natural principle (i.e., compositions that increase NAD+ biosynthesis) that rendered the claims patent-ineligible.”

The lesson here is that when walking the line of Section 101, a failure to include any “markedly different characteristics” in the claims of a patent can be a fatal mistake. The plaintiffs might have had more luck had they claimed an actual method for isolating the NR and had they kept in mind that claiming many elements in the alternative invites validity challenges, since the presence of just one listed element (such as sugar) in the prior art can invalidate such a claim.

On February 3, 2023, the Southern District of California found a patent infringement case exceptional under 35 U.S.C. § 285 and awarded the defendant, Cerner Corporation (“Cerner”), its attorney’s fees after the plaintiff, CliniComp International, Inc. (“CliniComp”), pursued ever-shifting infringement theories even after Cerner served it with an Octane Fitness letter. As this case demonstrates, a patentee faces substantial risks in pressing a case with shaky infringement theories. The case also underscores the value of Octane Fitness letters in forcing patentee-plaintiffs to confront those risks.

In December 2017, CliniComp sued Cerner for infringing its healthcare system patent, which claimed a method for managing the electronic information of multiple hospitals via a partitioned database. The key limitation, “storing,” concerned how the data would be stored and structured in the database. In response to Cerner’s inter partes review (“IPR”) challenge, CliniComp distinguished the patent from the prior art based on a narrow construction of the “storing” limitation which required “a very specific type of partitioning.” After prevailing in the IPR, CliniComp argued to the Court that the “storing” term should simply be construed according to its plain and ordinary meaning. However, the Court incorporated numerous disclaimers from the IPR into the claim construction of the term.

This construction created problems for CliniComp’s infringement theory, and CliniComp served Amended Final Infringement Contentions. Cerner not only moved for summary judgment (“MSJ”) of non-infringement, but also sent CliniComp an Octane Fitness letter informing CliniComp that its claims were “objectively meritless and inconsistent with the Court’s claim construction rulings,” and that Cerner would seek fees if the lawsuit was not immediately dismissed. CliniComp did not dismiss, and instead responded to the MSJ with a second, different infringement theory unsupported by its contentions. Then, after requesting a sur-reply to the MSJ, CliniComp advanced a brand-new third infringement theory. Finally, in a hearing on the MSJ, it advanced a fourth theory. The Court found three of these theories were improperly advanced, that Cerner did not practice any of them, and thus granted Cerner’s MSJ.

The Court found the case exceptional based on the “objective unreasonableness and substantive weakness of CliniComp’s litigating position following the conclusion of the IPR proceedings and the Court’s claim construction order.” The Court emphasized that a finding of subjective bad faith is not necessary to find a case exceptional, as meritless or baseless claims “may sufficiently set itself apart from mine-run cases to warrant a fee award.”

Cerner originally sought $925,000 (its fees incurred since the Court’s July 28, 2022, claim construction order) but the Court limited Cerner’s recovery to fees incurred after August 29, 2022, when CliniComp served its Amended Final Infringement Contentions. The Court noted: “By that point in time, CliniComp had ample time to assess the strength (or lack thereof) of its claim for patent infringement in light of the Court’s claim constructions and the relevant discovery. And at the point in time, CliniComp chose to continue with the litigation and assert what became a string of baseless and ever-changing theories of infringement.” The final amount of fees to be awarded has yet to be determined.

On January 27, 2023, a district court judge refused to grant a group of musicians class certifications in their copyright infringement efforts against their former record label, Universal Music Group (UMG). The district court found that the need for individualized proof in a work-made-for hire copyright case, such as the one at issue here, precludes class certification.

Section 203 of the Copyright Act provides a limited opportunity for authors to terminate a previous transfer of their copyright. Relying on Section 203, a group of musicians, including punk rock band “The Dickies,” alternative rock band “Dream Syndicate,” and rock singer Straw Harris, sought to terminate the copyright assignments in their recordings that they had previously granted to UMG. UMG refused to transfer the copyrights back to the musicians. UMG argued that the recordings were works-made-for-hire, making UMG the actual author of the works, hence, the copyright assignments were not subject to termination pursuant to Section 203. Disagreeing with UMG, the musicians filed suit and moved for an order certifying a class action on behalf of essentially all recording artists who served, or will serve, UMG termination notices pursuant to Section 203 between 2013 and 2031.

To certify a class, each member’s claim must have common issues both resolvable through generalized proof and are more substantial than the other issues affecting only individual members. UMG asserted that its work-made-for-hire defense defeats a class certification determination, because it would require “a fact-intensive inquiry based on various fact-based tests that cannot be resolved based on common proof.” The district court agreed. In considering the work-made-for-hire defense, the district court would have to evaluate evidence unique to UMG’s action with respect to each musician, each musician’s termination notice, and whether each musician’s sound recordings were “specially commissioned works” or “contributions to collective works.” All of these inquiries are individualized and fact-specific. The district court determined that the musicians failed to demonstrate that these inquiries were capable of resolution based on generalized proof. “The individualized evidence and case-by-case evaluations necessary to resolve those claims make this case unsuitable for adjudication on an aggregate basis.” The district court consequently declined to certify the class.

As noted by the district court, copyright cases are poor candidates for class-action treatment, because their similarities are superficial. While it is true that each member of the purported class is in a similar situation, and that the district court will have to apply the same type of legal analysis for each claim, the underlying facts for each member are different. Having to evaluate such individualized evidence will usually preclude class certification. This case serves as a cautionary tale for plaintiffs trying to certify a class based on copyright infringement.

We are pleased that Law360 Pulse has published Lisa Holubar’s and Ariel Katz’s article: “Pro Bono Work Is Valuable In IP And Continued Learning.” The article addresses a recent Rule change at the United States Patent and Trademark Office pertaining to CLE reporting and pro bono work as a form of CLE. Irwin IP attorneys are committed to providing free and reduced cost legal work to those in need and are proud to frequently partner with Lawyers for the Creative Arts to perform such work.

Read the full article on the law360 site or click here.