On October 18, 2024, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued a precedential decision in UTTO Inc. v. Metrotech Corp., No. 2023-145 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 18, 2024), ruling that a district court may engage in claim construction when determining a motion to dismiss. UTTO Inc. (“UTTO”) sued its competitor Metrotech Corp. (“Metrotech”), alleging patent infringement through the sale of its underground utility line locator device. The Federal Circuit vacated and remanded the district court’s dismissal of UTTO’s infringement suit for further claim construction proceedings to construe the disputed claim language, finding that a “fuller claim-construction analysis” was needed to define the scope of the claim language implicated in the 12(b)(6) motion.

UTTO’s asserted patent, U.S. Pat. No. 9,086,441, claims methods of detecting underground utility lines—i.e., “buried assets”—such as telephone or electrical lines. The methods include using GPS to identify a person’s location and then determine if the individual is within the buffer zone of a particular buried utility line without interference from conflicting signals from another buried line.

The district court had previously dismissed multiple iterations of UTTO’s complaint and had also denied UTTO’s motion for preliminary injunction wherein the district court construed the claim term “group” as more than one per the ordinary meaning and thus, construed a “group of buried assert data points” as requiring two or more data points for each buried asset. Based on this construction, the district court dismissed each iteration of UTTO’s complaint as Metrotech’s device used only one data point at a time and “as explained, the ’441 Patent requires the use of multiple data points to generate the buffer zone.” UTTO unsuccessfully argued that the district court had no authority to engage in claim construction when deciding a motion to dismiss, citing Nalco Co. v. Chem-Mod, LLC, 883 F.3d 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2018), wherein the Federal Circuit reversed a dismissal of patent infringement claims because the district court rested “on a premature resolution of claim-construction disputes.”

On appeal, the Federal Circuit rejected UTTO’s interpretation of Nalco, explaining that Nalco did not establish “a categorical rule against a district court’s adoption of a claim construction in adjudicating a motion to dismiss.” Additionally, the Federal Circuit explained that district courts have deference in resolving matters before them, and separate claim construction proceedings are not required. Finally, the Federal Circuit found passages of the specification for the ’441 Patent to require closer scrutiny as they appear to support UTTO’s proposed claim construction that group means one or more. The Federal Circuit also asked, “whether a relevant artisan would read the phrase [group of buried asset data points] in light of a recognized meaning of ‘group’ in mathematics to mean one or more, not two or more,” thereby prompting the remand. While strong intrinsic evidence may provide a basis for aggressively pushing for an early claim construction ruling in support of (or against) early motion practice, this case also provides a roadmap to push a court to avoid premature constructions based on solely intrinsic evidence.

Designing functional features on a device will not make you an inventor for design patents on the device! The District of Delaware (“the court”) recently held that Apple Inc.’s (“Apple”) design patents were not unenforceable due to inequitable conduct because Apple’s engineers did not design any ornamental features within its Apple Watch design patents and therefore were not inventors of the designs. The court also held Apple did not withhold any information from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“PTO”) indicating Apple knew its claimed designs were functional.

Apple brought a patent infringement suit against Masimo Corp. and Sound United, LLC. (collectively “Masimo”) alleging Masimo infringed Apple’s utility and design patents relating to Apple Watches. Masimo argued that Apple’s design patents were unenforceable because “(1) [] an Apple in-house patent agent and the named inventors of [Apple’s design patents] ‘knowingly withheld from the PTO … the names of the engineers who were actual inventors’; and (2) that those same individuals knowingly withheld ‘the functional nature of the claimed designs.’” Apple moved for summary judgment arguing that Masimo could not provide a triable issue as to either of Masimo’s theories. The court agreed with Apple and rejected each of Masimo’s theories.

First, the court held that Apple’s engineers were not required to be listed as inventors in Apple’s design patent applications. Masimo argued that Apple’s engineers were required to be listed as inventors because Apple’s PowerPoint presentations and deposition testimony indicated that the engineers contributed to the design of Apple’s watches. The court explained that these presentations and testimony related to the functional aspects of the watch designs, such as the wheel optical sensor design, and did not relate to whether the engineers contributed to the ornamental aspects of the claimed designs. Additionally, the court further explained that neither the named inventors of the design patents nor the engineers at issue themselves believed that the engineers should have been named as inventors. Therefore, the court held no reasonable factfinder would conclude that the named inventors or Apple’s in-house design patent agent knew that the omitted engineers contributed to the ornamental aspects of the claimed designs.

Second, the court held that Apple did not knowingly withhold any information relating to the functional nature of the claimed designs. Masimo cited to documents, testimony, and a separate utility patent application to argue that Apple’s design patent inventors and in-house design patent agent knew of the functional nature of the Apple Watch designs but did not disclose this information during the prosecution of Apple’s design patents. The court held that the inventors of the design patents and Apple’s in-house design patent agent, who only prosecuted Apple’s design patents, were not aware of Apple’s related utility patents and that Masimo failed to cite any additional evidence that the design patent inventors or Apple’s in-house design patent agent knew that the claimed designs were functional in nature or that these individuals withheld this information from the PTO with an intent to deceive.

In light of this decision, businesses should be cognizant as to whether its employees contributed to the functional or ornamental nature of a claimed design. If an employee contributed to the ornamental appearance of a design they must be listed as an inventor in a design patent application, whereas if the employee merely contributed to the functional aspects of the design, there is no requirement that the employee be listed as an inventor.

On October 3, 2024, the Federal Circuit held that a party may be liable for false advertising violations under Section 43(a)(1)(B) of the Lanham Act when it “falsely claims that it possesses a patent on a product feature” and advertises that product feature in a manner that misleads consumers about “the nature, characteristics, or qualities of its product.”

Crocs, Inc. (“Crocs”) is a large, well-known footwear and clothing company that mainly designs, manufactures, and markets foam footwear. In 2006, Crocs sued Double Diamond Distribution, Ltd. and several other competitors (collectively, “Dawgs”) for patent infringement. The case was stayed several times due to Section 337, inter parties review, and bankruptcy proceedings. In 2016, Dawgs filed a counterclaim against Crocs for false advertising violations under the Lanham Act. In 2017, Dawgs filed an amended counterclaim, asserting that Crocs engaged in a “campaign to mislead its customers” about the characteristics of the primary material in Crocs, “Croslite,” by deceiving its customers into believing that “Croslite” was a patented one-of-a-kind material.

The district court subsequently granted summary judgment in favor of Crocs, concluding that in light of Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 539 US 23 (2003), and Baden Sports, Inc. v. Molten USA, Inc., 556 F.3d 1300 (Fed. Cir. 2009), Dawgs had failed to state a cause of action under Section 43(a)(1). The district court determined that there was no cause of action because Crocs’ use of terms such as “patented,” “proprietary,” and “exclusive” were directed to Crocs “inventorship” of its products rather than nature, quality, or characteristics of its products.

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s ruling, reasoning that the case was distinguishable from Dastar and Baden. The Federal Circuit noted that Crocs conceded it did not possess patent protection for “Croslite,” and further rejected the district court’s reasoning that Crocs’ false claims were directed to the originality and inventorship of “Croslite.” According to the Federal Circuit, a cause of action under the Lanham Act arose because Crocs falsely claimed that “Croslite” was patented to mislead its consumers into thinking the primary material in Crocs possessed tangible benefits. The Federal Circuit agreed with Dawgs allegation that Crocs promotional materials “deceive consumers and potential consumers into believing that all other molded footwear … is made of inferior material compared to Crocs’ molded footwear.” Ultimately, the Federal Circuit reversed and remanded the case back to the district court for further proceedings.

This case is important for both consumers and competitors alike as it strengthens consumer protections by preventing false and misleading advertising claims, and unfair competition. Furthermore, due to the various methods of damages available under the Lanham Act, it is imperative that companies review their marketing and promotional materials to ensure that the company does not falsely advertise patent protection on a product feature.

The Federal Circuit’s en banc ruling in LKQ Corp. v. GM Global Tech., in which LKQ was represented by Irwin IP, marks a pivotal change in design patent law by overturning the long-standing “Rosen-Durling” test for assessing obviousness. This article examines the USPTO’s updated guidance in response to the decision and its broader implications for both design and utility patents.

Irwin IP is pleased to welcome our new Administrative Assistant, Katarina Evers. Katarina brings with her several years of experience in professional services, specializing in client relationship management and executive support. In her role at Irwin IP, she will be assisting with office operations and providing vital administrative support to our attorneys and staff.

We are excited to see the positive impact Katarina will have on our firm.

——–

Irwin IP specializes in mission-critical intellectual property and technology litigation, catering to a diverse client base, including Fortune 500 companies and innovative startups. Our expertise extends to enforcing and protecting intellectual property portfolios, ensuring our clients’ product lines, worth hundreds of millions annually, remain secure. Notably, we routinely, successfully litigate against the largest, most prestigious law firms representing the largest companies in the world on matters valued in the tens and hundreds of millions.

Gain insight into the intricacies of design patent obviousness and the pivotal federal circuit en banc trial for our client, LKQ Corporation, highlighting the latest developments and their implications for intellectual property law.

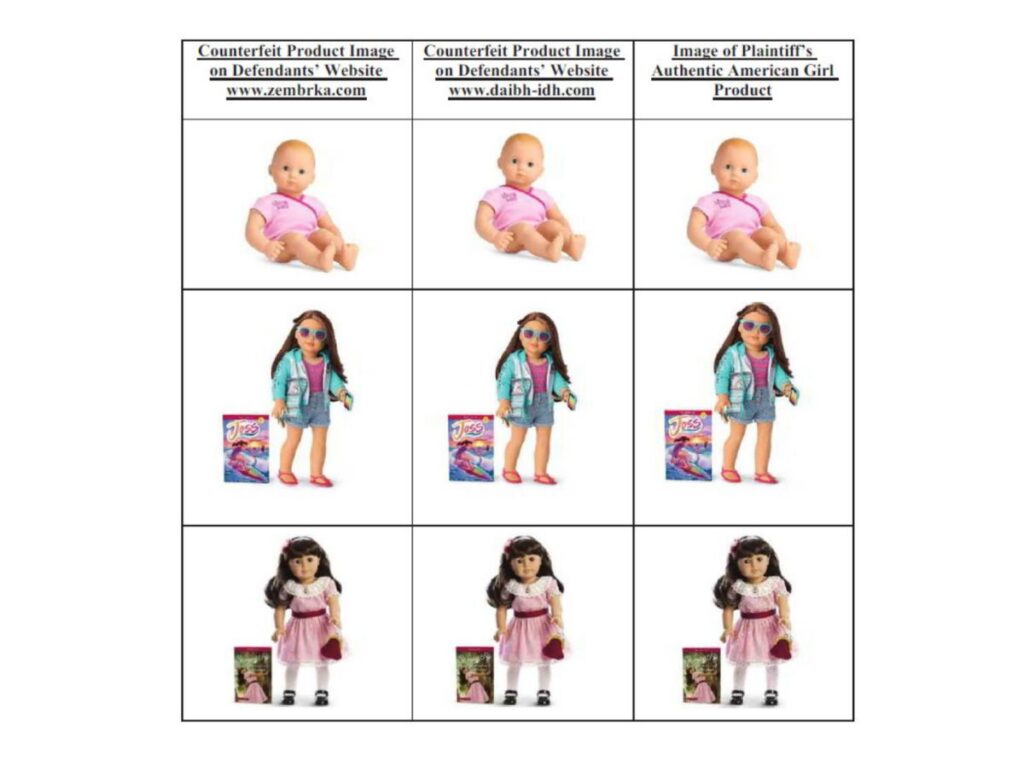

On September 17, 2024, the Second Circuit concluded that under New York’s Long Arm Statute, a business that receives a single product order, sends an order confirmation email, and accepts payment from a customer with a New York shipping address, “transacts business in New York” for purposes of establishing specific personal jurisdiction over a defendant. Personal jurisdiction attaches even if the defendant does not complete delivery of the order. The Second Circuit’s decision reversed the Southern District of New York’s grant of a China-based company’s motion to dismiss in a trademark counterfeit and infringement suit filed by the doll manufacturer, American Girl.

Zembrka, a Chinese company with no locations in New York, had allegedly been marketing, manufacturing, and distributing counterfeit American Girl products. Prior to filing suit, American Girl’s counsel purchased the allegedly counterfeit American Girl merchandise from Zembrka’s website and received a confirmation email and PayPal receipts for the orders. American Girl then sued Zembrka alleging that through its websites, Zembrka sold infringing American Girl products in New York and used American Girl’s marks on its websites. The District Court immediately granted a temporary restraining order (“TRO”) enjoining Zembrka from marketing or distributing counterfeit American Girl products.

Two weeks after Zembrka was served with the complaint, it canceled the orders, refunded the payments, and revoked its promise to ship the merchandise. After that, Zembrka filed a motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiciton. New York’s long arm statute provides that personal jurisdiction exists when the defendant “transacts any business within the state.” Zembrka argued that the court did not have personal jurisdiction over it because there was not shipment of goods to American Girl and American Girl’s payment was refunded. The District Court agreed and granted the motion to dismiss.

After the TRO was granted but before the motion to dismiss had been granted, there were at least 38 additional New York purchasers of Zembrka’s allegedly counterfit goods. Based on this new evidence, American Girl moved the District Court to reconsider its dismissal. The District Court denied American Girl’s motion for reconsideration because Zembrka also stopped shipment of those products and refunded all payments made. Because of that, the District Court held that no business transaction actually occurred for purposes of establishing personal jurisdiction. American Girl appealed.

On appeal, the Second Circuit reversed the District Court’s decision. The Second Circuit explained that New York’s Long Arm statute is a “single act statute” and the fact that Zembrka cancelled the orders and refunded payments does not change that the statute only requires a transaction, not a completed sale. Because Zembrka conducted at least one transaction in New York, personal jurisdiction was appropriate.

Plaintiffs should note that the Second Circuit appears to allow the manufacturing of jurisdiction, while companies should be aware that a single act such as accepting an order, even if no sale occurs, can be sufficient for a court to assert personal jurisdiction and then be hauled into court, at least in New York.