In invalidating a claim as obvious on remand, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (the “PTAB”) recently held that the PTAB bears the burden of persuasion regarding prior art raised sua sponte, despite precedent that the petitioner must bear the burden.

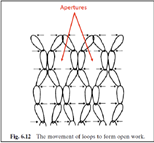

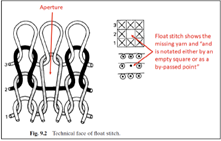

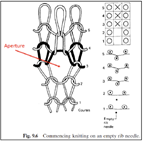

Adidas petitioned for inter partes review (IPR) of Nike’s U.S. Patent No. 7,347,011 (directed to articles of footwear having a knitted textile “upper” portion). The PTAB’s first decision was remanded by the CAFC due to error by the PTAB in failing to fully consider one of Nike’s substitute claims as well as Nike’s Graham factor evidence. On remand the PTAB issued a decision which relied sua sponte on a knitting manual known as “Spencer” (shown below with Petitioner’s annotations) that was introduced by Petitioner on the evidentiary record for informing its expert’s declaration (and also relied upon by Nike’s expert), but never cited by the Petitioner as grounds for unpatentability of the claim in question. On a second appeal, the CAFC held that this violated the Administrative Procedure Act—the PTAB may identify an issue of patentability on its own based on the evidentiary record, but it must notify the parties of this issue and provide adequate notice and opportunity for response through supplemental briefing or oral argument.

Now able to respond to Spencer, Nike argued that the manual taught different techniques to create apertures. The PTAB found this unconvincing, finding that Nike seemingly argued that the reference would need to disclose this limitation in haec verba without taking into account the reasonable inferences of an ordinarily skilled artisan.[1]

Interestingly, the PTAB also determined that the Board itself bears the burden of persuasion on sua sponte grounds for unpatentability, rejecting Nike’s application of precedent that Adidas should bear the burden notwithstanding not having raised the issue.[2] The most valuable takeaways from this case for litigants in post grant proceedings are that of the invaluable flexibility of a robust evidentiary record. The PTAB’s administrative discretion is extremely broad, and a well-developed field of prior art on the record renders the challenged patent as vulnerable as possible.

[1] See In re Preda, 401 F.2d 825, 826 (CCPA 1968).

[2] See, Bosch Auto. Serv. Sols., LLC v. Matal, 878 F.3d 1027, 1040 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (holding generally that Petitioner bears the baseline burden of showing that even substitute claims are unpatentable in a post grant proceeding).

Irwin IP is pleased to announce that on March 11, 2021, Honorable Robert W. Gettleman entered an Order awarding Irwin IP client Oasis Legal Finance Operating Company, LLC (“Oasis”) approximately $3.1 million for attorneys’ fees and nontaxable costs (the full amount requested) against Oasis’s former CEO, Gary Chodes; his business associate; and his personally-held entities (collectively, “Chodes”). In awarding Oasis its fees and costs, Judge Gettleman noted the exceptional nature of Chodes’ infringement and the frivolous litigation positions taken by Chodes. The court also noted that it “thoroughly reviewed plaintiff’s timesheets and finds no reason to reduce the fees requested.” Barry Irwin, Lisa Holubar, and Adam Reis were the key Irwin IP attorneys who worked to obtain this win and we congratulate them on a fantastic result. This latest decision follows three previous decisions in Oasis’ favor: A Summary Judgment on Ownership Issues, A Summary Judgment on Infringement, and A Maximum Statutory Damage Award.

Irwin IP is proud to announce that its associate, Peter Danos, recently had his article entitled, “Supreme Court to Decide Whether a Patent is a Compensatory Interest under the Fifth Amendment” published on the Online Publication @theBar. In his article, Peter discusses the Federal Circuit’s determination in Christy Inc. v. United States, 971 F.3d 1332 (Fed. Cir. 2020) that the invalidation of a patent via an inter partes review (“IPR”) is not a compensable taking under the Fifth Amendment, and the Supreme Court’s decision to review that decision. Congrats, Peter! Keep up the good work.”

Click the link below for the full article: https://cbaatthebar.chicagobar.org/2021/03/08/supreme-court-to-decide-whether-a-patent-is-a-compensatory-interest-under-the-fifth-amendment/

Irwin IP is excited to announce that Daniel Zhang has joined our team as a lateral associate. Daniel focuses on trademark litigation matters, and while attending law school, Daniel represented various clients in trademark and patent matters with the University of Miami’s Startup Practicum. We’re very excited to have him join our team.

Irwin IP recently settled a long-fought copyright battle on behalf of its client Massarelli’s Lawn Ornaments, Inc. (“MLO”), a leading manufacturer of concrete garden statuary. Two years ago, MLO discovered a replica of one of its statues in a HomeGoods store. MLO learned that a Chicago-based manufacturer, Continental, was the supplier of the statue and that Continental was making two other infringing statues. MLO filed suit for copyright infringement of the three works. After defeating a summary judgment motion, [view announcement here], and defending a claim brought by Continental’s insurance provider denying coverage, MLO obtained a favorable settlement.

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) recently issued a decision focusing on the doctrine of equitable intervening rights. Specifically, the CAFC affirmed that equitable intervening rights can apply even if a party has already recouped its investment in the infringing technology.

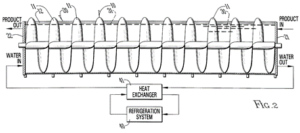

John Bean Technologies Corporation (“John Bean”) is the owner of U.S. Pat. No. 6,397,622 (the “’622 patent”). The ’622 patent covers an auger-type poultry chiller used to help process poultry for human consumption. Morris & Associates, Inc. (“Morris”), John Bean’s competitor, on June 27, 2002, wrote a demand letter to John Bean, expressing its belief that the ’622 patent was invalid and disclosing allegedly invalidating prior art references. Morris received no response and thus, developed and sold chillers that included features in the ’622 patent. Over a decade later, on December 18, 2013, Bean filed an ex parte reexamination of the ’622 patent before the United States Patent Office (the “USPTO”), and ultimately amended two claims and added six new claims. John Bean then sued Morris for infringement. Morris moved for, and the District Court granted, summary judgment, barring the infringement claims based on equitable intervening rights. John Bean appealed.

John Bean Technologies Corporation (“John Bean”) is the owner of U.S. Pat. No. 6,397,622 (the “’622 patent”). The ’622 patent covers an auger-type poultry chiller used to help process poultry for human consumption. Morris & Associates, Inc. (“Morris”), John Bean’s competitor, on June 27, 2002, wrote a demand letter to John Bean, expressing its belief that the ’622 patent was invalid and disclosing allegedly invalidating prior art references. Morris received no response and thus, developed and sold chillers that included features in the ’622 patent. Over a decade later, on December 18, 2013, Bean filed an ex parte reexamination of the ’622 patent before the United States Patent Office (the “USPTO”), and ultimately amended two claims and added six new claims. John Bean then sued Morris for infringement. Morris moved for, and the District Court granted, summary judgment, barring the infringement claims based on equitable intervening rights. John Bean appealed.

The intervening rights doctrine, codified in 35 U.S.C. §252, extends to reexamined patents under 35 U.S.C. §307(b) and limits an alleged infringers pre-existing liability with respect to amended or new claims. If applicable, “an infringer may continue what would otherwise be infringing activity after a reissue or reexamination.” Seattle Box Co. v. Indus. Crating & Packaging, Inc., 756 F.2d 1574, 1579 (Fed. Cir. 1985). The policy behind this doctrine “is that the public has the right to use what is not specifically claimed in the original patent.” Id. (citing Sontag Chain Stores Co. v. Nat’l Nut. Co., 310 U.S. 281, 290 (1940)). The District Court considered six factors in granting summary judgment: (1) whether substantial preparation was made by the infringer before the reissue; (2) whether the infringer continued manufacturing before reissue on advice of counsel; (3) whether there was existing orders or contracts; (4) whether non-infringing goods can be manufactured from the inventory used to manufacture the infringing product and the cost of conversion; (5) whether there is a long period of sales and operations before the patent reissued from which no damages can be assessed; and (6) whether the infringer made profits sufficient to recoup its investment. The court found the factors to weigh in Morris’s favor and likely bad faith by John Bean.

On appeal, John Bean argued that the District Court gave insufficient weight to the fact that Morris recouped its investment and refused to quantify its profits. Specifically, John Beane claimed that Morris had recouped the entirety of its monetary investments prior to the grant of the reissue patent. As such, John Bean argued that Morris’s investment no longer needed “protection” and, thus, there should be no grant of intervening rights. As a matter of first impression, the CAFC determined that 35 U.S.C. §252 does not provide that “monetary investments made and recouped before reissue are the only investments that a court may deem sufficient to protect as an equitable remedy.” The CAFC found that while recoupment is an acceptable factor for consideration, it is not “the sole factor,” nor dispositive, when the court balances the equities. The CAFC emphasized the broad equity powers afforded to the District Court and noted its consideration of six factors in concluding that Morris was entitled to intervening rights. Thus, the CAFC affirmed the District Court’s ruling, finding that it had not abused its discretion.

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) affirmed a final judgment ruling that Infinity’s four patents—involving using a fax machine as a printer or scanner for a personal computer—are invalid as indefinite because the patent applicant had asserted conflicting definitions of the claim term “passive link” during prosecution and reexamination of one of the patents. Infinity underscores the hazards of leveraging vague distinctions during prosecution to avoid prior art, as any reprieve may be short-lived.

Infinity sued Oki Data for infringing a family of patents directed to connecting a fax machine directly to a computer so it could be used as a printer or scanner. All of these patents, including the earliest asserted patent, No. 6,894,811 (“the ’811 Patent”) claimed priority to U.S. Patent App. Ser. No. 08/226,278. Critically, all of the asserted claims required that image data be exchanged “via a passive link between the facsimile machine and the computer,” yet the specification contained no explanation of what a “passive link” meant. The “passive link” limitation was only introduced during prosecution of the ’811 Patent to avoid a potentially anticipatory prior art reference, Perkins, which disclosed a fax modem device for achieving that same functionality. The applicant argued its invention differed from Perkins by connecting the fax machine to the computer via a “passive link,” thus directly connecting the fax machine transceiver to the computer’s I/O bus without any intervening circuitry. Supporting this new limitation, the applicant submitted additional figures depicting a fax machine connected directly to a computer that lacked an internal fax modem. However, this maneuver created problems later: in reexamination, the applicant faced another prior art reference, Kenmochi, that disclosed and predated the figures introduced to support the “passive link” limitation. To antedate Kenmochi, the applicant claimed priority to the earlier ’278 Application, successfully arguing that the “passive link” was disclosed in its original figures depicting a fax machine connected to a fax modem installed on board a computer.

Returning to the present case: Oki Data, argued during claim construction that the applicant had taken inconsistent positions to overcome Perkins and antedate Kenmochi, rendering the claim terms indefinite. The district court agreed, finding that the applicant’s contradictory statements precluded a person of ordinary skill from understanding with reasonable certainty where the “passive link” ends and the “computer”begins—whether at the I/O bus or the data port of an on-board modem. The CAFC affirmed, agreeing that “holding Infinity to both positions results in a flat contradiction” that violates the public-notice function of patent claims. Although the patent applicant’s aggressive maneuvering around the prior art staved off invalidity for a time, it ultimately forced the applicant to advance inconsistent constructions and an untenable priority claim, trapping the claims between the written description requirement and the prior art.

Irwin IP is excited to announce that Barry Irwin has been named a Leading Lawyer for a 17th straight year by Law Bulletin Media.

https://law-arts.org/lca-announces-transitions-its-executive-committee

A Magistrate Judge for the Southern District of New York recently issued a Report and Recommendation (“R&R”) concluding that the color pattern of a traditional Rubik’s cube was not functional and thus entitled to trademark protection.

Rubik’s Brand Limited (“RBL” or “Rubik’s”) sued Flambeau, Inc. (“Flambeau”) alleging infringement of RBL’s trademark registration on the design of the standard 3×3 Rubik’s Cube puzzle by Flambeau’s 3×3 puzzle cube call the “Quick Cube.” The designs of the two cubes are depicted below:

Rubiks Cube Quick Cube

Flambeau moved for summary judgment on all claims. In so doing, Flambeau challenged the validity of the registration in the Rubik’s Cube’s trade dress under the doctrine of functionality. Trademark functionality serves to preclude trademark protection of useful products, and it comes in two varieties: utilitarian and aesthetic.

Utilitarian functionality assesses: “(1) whether a particular feature or appearance is ‘essential’ to the use or purpose of a product; or (2) whether that feature or appearance affects the cost or quality of the product.”[1] Essential means “dictated by the functions to be performed by the product.” Flambeau argued that the Rubik’s Cube design was essential because the combination of smaller cubes and colors allowed the puzzle to be manipulated and solved. But RBL’s trade dress registration did not cover the general elements of a cube puzzle; rather, it was specifically limited to “a black cube … with the color patches on each face being the same and consisting of the colors red, white, blue, green, yellow, and orange,” and Flambeau failed to show the overall impression of these specific elements was essential to the use of the product. Regarding cost, Flambeau argued that the use of black plastic and colored stickers were the most cost-effective way to manufacture a cube puzzle, but Flambeau failed to offer any supporting evidence. Regarding quality, Flambeau argued that the specific colors chosen for the Rubik’s Cube provided the best possible contrast for purposes of solving the cube. The Magistrate rejected this argument, noting it is speculation given the near infinite number of alternatives that could be used and that Flambeau offered no evidence that “solvability” was an appropriate metric for the quality of the product.

The Magistrate Judge also found Flambeau failed to satisfy the test for aesthetic functionality, which assesses whether acknowledging the contested trademark or trade dress would “put competitors at a significant non-reputation-related disadvantage.”[2] As noted, because the registration was specific to a black base and specific color stickers, the Magistrate Judge found nothing about the registration that significantly hindered competitors.

After rejecting Flambeau’s functionality arguments, the Magistrate Judge considered RBL’s claims, ultimately recommending that the issue of likelihood of confusion be sent to a trial. In the end, Rubik’s was saved by its decision to seek narrow protection on its trade dress. Nonetheless, this case highlights the increasing prevalence of trademark functionality.

[1] Rubik’s Brand Limited, 2021 WL 363704, at *6 (quoting Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent Am. Holding, Inc., 696 F.3d 206, 217, 219 (2d Cir. 2012)).

[2] Id. at *11 (quoting Christian Louboutin, 696 F.3d at 221).