On August 11, 2021, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) held that the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) erred in construing a key term—“fixed”—in the patent claims too narrowly. After construing the term to have special meaning, and relying on extrinsic evidence to support that finding, the PTAB determined that Seabed Geosolutions (US) Inc. (“Seabed”) failed to show that Magseis FF LLC’s (“Magseis”) RE45,268 patent (“’268 Patent”) was invalid as anticipated or obvious in an inter partes review. However, the Federal Circuit rejected that reasoning, finding the PTAB’s use of extrinsic evidence to be improper, and held that the term, “fixed,” should be construed to have its ordinary meaning.

The ’268 Patent covers oil and gas seismic exploration using seismometers, which involves sending a signal into the earth and using geophones to detect seismic reflections. Each claim included that the “geophone internally [was] fixed within” either a “housing” or “internal compartment” of a seismometer.

On April 27, 2018, Seabed petitioned for inter partes review of the ’268 Patent on multiple grounds, including obviousness. The PTAB construed the phrasing “geophone internally fixed within [the] housing” to require a non-gimbaled geophone. This finding was based on extrinsic evidence that, according to the PTAB, supported the conclusion that “fixed” had a special meaning in the relevant art at the time of the invention—i.e., “not gimbaled”—rather than an ordinary meaning. In light of this narrow construction, the PTAB held that the cited prior art did not disclose the “fixed” geophone limitation.

The CAFC declined to follow the PTAB’s reasoning. The CAFC noted that the PTAB was required to use the broadest reasonable interpretation standard to construe claim terms (as this case predated November 13, 2018 when the standard was changed); but, more important, the CAFC also noted that intrinsic evidence—which includes considering the patent claims, specification, and prosecution history—should be given primacy in any claim construction analysis. Extrinsic evidence should only be considered if it is consistent with the intrinsic evidence. If the meaning of a term is clear from the intrinsic evidence, there is no reason to use extrinsic evidence to interpret a term.

The CAFC found that the PTAB erred in relying on extrinsic evidence to alter the meaning of the word “fixed” when it was clear from intrinsic evidence that “fixed” merely meant “mounted or fastened inside.” The specifications disclosed that a geophone was “internally mounted within” the seismometer housing and did not mention gimbaled geophones. Further, the prosecution history supported this interpretation. As such, the intrinsic evidence as a whole supported an interpretation of “geophone internally fixed within [the] housing” that did not include gimbaled geophones.

This case demonstrates how the outcome of a patentability analysis can hinge on a single term. And because claim construction “begin[s] with the intrinsic evidence,” it is important to consistently elucidate in a patent’s specification what is (and what is not) within the meaning of the terms used in the patent and its claims.

The Federal Circuit’s (“CAFC”) recent decision in CommScope Techs. provides an important reminder regarding proving literal infringement, as well as some tips on preserving an issue for appeal. At trial, both CommScope and Dali alleged infringement of multiple patents. Following trial, both parties appealed several decisions. The CAFC, however, focused on just two: the denial of CommScope’s motions for judgment as a matter of law of no infringement and invalidity of Dali’s U.S. Patent No. 9,031,521 (“the ’521 patent”).

The ’521 Patent claims a system and method for resolving wireless signal amplification issues through a training mode where a feedback loop updates a lookup table to calculate digital adjustments to the output signal. Significantly, the ’521 Patent includes a limitation requiring “switching a controller off.” In the district court, Dali asserted that the phrase “switching a controller off,” did not require construction, while CommScope argued—and the district court agreed—that it should be construed to mean placed in a nonoperating state. Ultimately, the jury found the ’521 patent infringed and not invalid.

On appeal, CommScope challenged infringement and validity, relying on the district court’s claim construction of “switching a controller off,” arguing that its controller was never placed in a nonoperating state.

Dali tried to defend the infringement finding by asserting the district court’s claim construction was wrong. The CAFC rejected Dali’s challenge, highlighting three missteps. First, Dali only raised the claim construction issue in a footnote in its appeal brief, and any such argument is forfeited. Second, Dali’s appeal of the construction was a single sentence, and thus insufficiently developed. Third, Dali presented inconsistent positions, attacking the district court’s claim construction to uphold infringement, while defending it for validity. The CAFC adopted the district court’s construction finding there was no apparent dispute because Dali’s challenge was ineffectual.

Scrutinizing the evidence in light of the district court’s claim construction, the CAFC reversed the denial of no infringement, rejecting the testimony of Dali’s expert who failed to use the district court’s claim construction and therefore, per the CAFC, effectively offered no evidence to support the infringement verdict on that limitation. Dali argued that the distinction between the construction used by its expert and the district court was “hairsplitting.” But the CAFC emphasized that literal infringement ascribes significant meaning to construed claims, which must read “on the accused device exactly,” noting a party cannot argue construction one way for infringement and another for invalidity. CommScope Techs. LLC v. Dali Wireless Inc., 2021 WL 3731854, at *6 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 24, 2021).

In sum, CommScope Techs. provides a nice reminder regarding the necessary rigor to preserve issues for appeal, and the importance, when seeking to prove literal infringement, of addressing each and every limitation.

On August 2, 2021, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) held that an employment agreement stating that an employee’s future patents “shall be the property of the University [of Michigan]” did not create a present automatic assignment of the asserted patents to the University. Thus, the Court held that the plaintiff corporation, Omni MedSci, an entity formed by the inventor, Dr. Muhammad Islam, had standing to bring the lawsuit enforcing the patents. This case underscores the meticulousness required of patent assignment provisions and should prompt employers to revisit their employees’ contracts to ensure those contracts achieve the desired allocation of rights.

Dr. Islam joined the University of Michigan faculty in 1992 as an assistant professor of engineering and computer science. At around that time, he executed an employment agreement wherein he agreed to abide by the University’s rules and regulations. These included Bylaw 3.10, which provided in relevant part:

Patents … issued or acquired as a result of or in connection with administration, research, or other educational activities conducted by members of the University staff and supported directly or indirectly . . . by funds administered by the University . . . and all royalties or other revenues derived therefrom, shall be the property of the University.

Order, at 2 (emphasis added). The patents-in-suit originated from provisional applications Dr. Islam filed while on an unpaid leave of absence from the University in 2012 and assigned to Omni in 2013, notwithstanding continuing disagreement with the University over who rightfully owned them. Then, in 2018, Omni brought the lawsuit at issue against Apple in the Eastern District of Texas.

Apple moved to dismiss the action for lack of standing on the basis that Dr. Islam’s employment agreement effectuated a present automatic transfer of rights in the invention to the University, instantly transferring ownership of the patents-in-suit to the University upon issuance and thus invalidating their assignment to Omni. Omni argued that the invention was outside the scope of the assignment obligation altogether. The Eastern District of Texas did not adjudicate that question, but denied the motion, finding that Bylaw 3.10 was “at most, a statement of future intention to assign.” Following transfer to and rehearing by the Northern District of California, that court upheld the denial. Apple filed an interlocutory appeal.

The CAFC agreed with the district courts, holding the Bylaw to be “a statement of an intended outcome rather than a present assignment.” The Court noted that, by its own terms, the Bylaw “stipulate[d] the conditions governing the assignment of property rights,” similar language had been held to denote an obligation to assign rather than an assignment in and of itself. In essence, the UM contract lacked a present-tense active verb that would have effectuated the assignment automatically. In light of this decision, it would be in businesses’ interest to revisit their employment agreements and ensure they allocate rights in the manner intended.

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) has again ordered a judge from the Western District of Texas to transfer a patent case into the Northern District of California. Specifically, the CAFC held that courts should disregard plaintiff’s pre-litigation attempts to manipulate venue when determining whether an action “might have been brought” in a transferee district under 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a).

Ikorongo Tech (“Tech”) owns four patents (“asserted patents”) directed to the functionality of third-party applications that run on mobile devices. On or about March 3, 2021, Tech, located in North Carolina, spun off Ikorongo Texas LLC, an alleged “unrelated” company, despite having the same owners as Tech and operating out of the same North Carolina office. Approximately ten days before filing suit, Tech assigned to Ikorongo Texas the exclusive rights to sue for infringement within the Western District of Texas, while simultaneously retaining the rights to the asserted patents throughout the country (the “licensing agreement”). Ikorongo Texas subsequently sued Samsung and LG in the Western District of Texas. The next day, Ikorongo amended the Complaint, listing Tech as a co-plaintiff. The Amended Complaint accused Defendants of patent infringement based on third-party applications running on Samsung and LG’s products. Defendants subsequently moved under U.S.C. § 1404(a) to transfer suit to the Northern District of California. The District Court denied the request, finding that the defendants failed to establish the threshold requirement that the complaints “might have been brought” in the Northern District of California. In that regard, the District Court stated that the relevant inquiry was “where [Defendants] committed any alleged acts of infringement as to Ikorongo Texas.” And given the fact that the scope of the Ikorongo license was limited to the Western District, any alleged infringement by Defendants could have only occurred within the Western District of Texas. In short, the Plaintiffs successfully influenced venue through the licensing agreement purporting to limit where a patent infringement suit might have been brought. The Court also analyzed the traditional public- and private-interest factors, but concluded they did not warrant transfer. The defendants then sought writs of mandamus to force transfer to the Northern District of California.

Under the All Writs Act, the CAFC may issue a writ if three conditions are met: “(1) the petitioner ‘[must] have no other adequate means to attain … relief’; (2) the petitioner must show that the right to mandamus is ‘clear and indisputable’; and [3] the court ‘must be satisfied that the writ is appropriate under the circumstances.'” Id. (internal citations omitted).

The CAFC granted the mandamus, finding that the District Court improperly disregarded the pre-litigation acts by Tech and Ikorongo Texas aim at manipulating venue. Specifically, “the presence of Ikorongo Texas is plainly recent, ephemeral, and artificial – just the sort of maneuver in anticipation of litigation that has been routinely rejected … therefore, we need not consider separately Ikorongo Texas’s geographically bounded claims.” Accordingly, the CAFC found that the underlying dispute “might have been brought” in the Northern District of California, as this is where the third-party applications were developed and significant business activities occurred. The CAFC also found that the District Court abused its discretion in balancing the traditional factors, as no potential witnesses or sources of proof existed in the Western District of Texas, and the Western District of Texas had no more of a local interest than other venues simply because suit was filed there.

This ruling is important, as it demonstrates that certain types of pre-litigation manipulation will not be tolerated when determining where an action “might have been brought.”

Irwin IP is pleased to share that Barry Irwin has received the “Best Lawyers in America” designation by US News and World Report. Best Lawyers are selected after a rigorous evaluation and include the Top 5% of private practitioners. Irwin IP thanks all of those who were involved in the submission, evaluation, and review process.

In the latest trademark case spurred by Covid-19, the District Court of Arizona (“the court”) denied Arizona Board of Regents’ (“ASU”) motion for default judgment for a permanent injunction against an Instagram user because the vulgar Covid-related messages from the user (“John Doe”) did not rise to the level of trademark infringement.

ASU owns various trademarks for “ASU” or “Arizona State University” for different goods and services. ASU also owns trade dress for the school’s maroon and gold colors which are used in ASU’s promotional materials as well as ASU’s social media accounts. Around July 19, 2020, John Doe created an Instagram account called “asu_covid.parties.” The account touted itself as “throwing huge parties at ASU.” John Doe’s first message used the ASU logo and ASU’s maroon and gold trade dress. His later messages did not use ASU’s trade dress or colors but continued to use ASU’s logo and word marks. Doe’s messages touted that it would throw parties “like… if COVID never existed” and that masks would be banned for health and security reasons. Doe’s messages were laced with profanity and made numerous criticisms of ASU for requiring masks and Covid-19 testing, including: “Do not let Führer Crow force you to wear a mask or test.”. After Instagram would not remove or modify Doe’s account, ASU filed a trademark complaint naming Facebook (the parent of Instagram) and Doe as defendants. Facebook was dismissed after it agreed to disable the account and to prevent Doe from creating new accounts. Doe filed an answer to the complaint, but the court struck it as it was filled with “obscenities, inflammatory language, and insults directed toward [ASU] and its counsel.” Doe thereafter refused to participate in the case. ASU moved for default judgment and permanent injunction.

The court noted it had discretion whether to enter a default judgment under the seven Eitel factors. Although several of the factors favored entry of default, the merits of the claims and the sufficiency of the complaint factors did not. ASU claimed the unauthorized use of its marks likely caused confusion as to ASU’s affiliation, endorsement, or sponsorship of Doe’s “hoax” party, Doe’s “covid.parties” account, and the account’s messages. The court disagreed and found that a reasonably prudent consumer would not be deceived or confused into believing that ASU was the “source or origin” of the messages. The court explained only one of the posts used both the ASU logo and ASU’s trade dress, and that no university would drop the “f-bomb” in a party invitation. Likely anticipating said conclusion, ASU also argued that “even if a consumer were to conclude, after reading one or more posts by [Doe] that the account may not be affiliated with ASU, there is nevertheless actionable initial interest confusion.” The court disagreed and said Doe’s comments were too crude to create initial confusion and, stated more broadly that “it cannot be the case that every social media post written by a college student that happens to use the school’s colors and/or logo in the post creates initial interest confusion and qualifies as an actionable trademark violation.” The court thus dismissed the case.

This court’s decision will likely serve as precedent for individuals who create parody social media accounts of schools and other public institutions. This case is also of note due to its narrow view of initial interest confusion, a doctrine developed when e-commerce was in its nascent stages, but which has fallen out of favor as online shopping has evolved. Indeed, days before this decision, an Eighth Circuit litigant petitioned for certiorari to resolve whether courts can impose trademark liability based on initial interest in a mark, even where consumers are not confused as to source by the time they complete their purchases.

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) held that the Patent and Trademark Appeal Board (“PTAB”) erred by placing the burden of establishing that a purportedly anticipatory prior art reference was enabling on the challenger rather than requiring the patentee to establish that it was non-enabling. Notwithstanding that error, the Court affirmed the PTAB’s finding of no anticipation but vacated the PTAB’s non-obviousness determination as tainted by a mathematical error. This rollercoaster followed Apple Inc. (“Apple”)’s appeal of the PTAB decision sustain the validity of Corephotonics, Ltd.’s (“CorePhotonics”)’s cell phone camera patents.

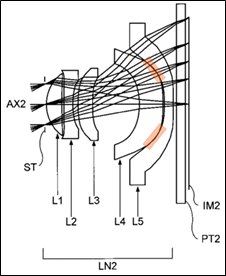

The U.S. Patent No. 9,568,712 (“the ’712 Patent”) claims a miniature telephoto multi-lens assembly with a total track length (the length of the lens assembly) that is smaller than its effective focal length. Longer focal lengths can improve image quality and reduce optical distortion. However, increasing focal length usually entails increasing total length, which is a problem for a camera meant to fit in a phone.

Apple’s anticipatory reference, Konno, disclosed a lens assembly (right) with the required focal length ratio. However, the PTAB found it non-anticipating because the embodiment was inoperable: as disclosed, the fourth and fifth lenses slightly overlapped (marked orange). While the patent owner typical bears the burden of providing inoperability in other proceedings, the PTAB distinguished those situations as not “in the context of AIA trial proceedings,” and not only placed the burden to prove enablement on the challenger, but further refused to consider Apple’s “new” enablement evidence submitted with its Reply. The Federal Circuit found the PTAB’s burden allocation and refusal to consider Apple’s Reply evidence constituted error.

However, the CAFC found these errors were harmless because Apple itself had asserted in its Petition that Konno’s asserted embodiment contained the error, arguing it was obvious for a Person of Ordinary Skill in the Art, or “POSA,” to correct. The law of anticipation, though, is inflexible: inoperative embodiments cannot anticipate. Apple’s argument may have succeeded for an obviousness-based ground, but its Petition asserted only anticipation against most claims, and only asserted obviousness against select dependent claims. As such, the CAFC affirmed the PTAB’s decision that Konno did not anticipate.

Although non-precedential, the decision is important because requiring the petitioner to have addressed this defense in the petition, as the PTAB did, rather than letting the dispute develop, would have caused confusion and inefficiency for this defense and other potential defenses. The case also underscores the importance, when practicing within the AIA trial framework where a challenger is restricted to the grounds asserted in its petition, of backstopping anticipation-based grounds with obviousness, just in case.

On May 11, 2021, The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”) held two Pacific Biosciences of California, Inc. (“PacBio”) patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 9,546,400 and 9,772,323 (the ’400 and ’323 Patents), invalid for lack of enablement under 35 U.S.C. § 112. PacBio had asserted these patents against Nanopore Technologies, Inc. and Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Ltd. (collectively “Oxford”) in the District of Delaware. The jury found the patents infringed, but not enabled. This case illustrates the hazards of stretching one’s claim to cover more than one has yet invented.

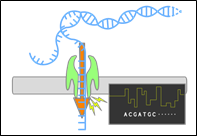

PacBio’s two patents in suit, which share a specification, claim methods for high-throughput genetic sequencing by passing a polynucleotide chain (such as DNA or RNA) through a small aperture (the “nanopore”) via an electric current. Individual nucleotide bases are then identified by monitoring changes in the electrical current. The patents provide more technically correct figures, but, as is often the case, Wikipedia best illustrates the gist:

PacBio’s two patents in suit, which share a specification, claim methods for high-throughput genetic sequencing by passing a polynucleotide chain (such as DNA or RNA) through a small aperture (the “nanopore”) via an electric current. Individual nucleotide bases are then identified by monitoring changes in the electrical current. The patents provide more technically correct figures, but, as is often the case, Wikipedia best illustrates the gist:

Enablement requires that a patent’s disclosure teach the full scope of the claimed invention such that a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSA) could practice it without undue experimentation.[1] This determination is guided by the eight Wands factors.[2] PacBio relied on expert testimony that at the time a POSA would have been able to practice the claimed method on synthetic DNA simulating a specific “hairpin” aberration. However, the claims covered all types of nucleic acid templates. And, Biological DNA was never successfully sequenced via nanopore technology until 2011, two years after the patents’ 2009 priority date. Further, a 2012 conference audience’s reaction to Oxford’s announcement of having done so signaled that it represented a major advancement even then. Thus, a POSA as of the priority date and with the disclosure of ’400 and ’323 patents may have been able to perform some very limited types of nanopore sequencing, but not for the full range of nucleic acids claimed.[3]

Enablement supports the foundational quid pro quo of patent law: you disclose how your invention works in exchange for a time-limited monopoly on it. A patent applicant may be tempted to cut the track and patent more than it has yet successfully reduced to practice (e.g., to get the jump on its competitors), but does so “at the peril of losing any claim that cannot be enabled[.]”[4]

[1] McRO, Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games America Inc., 959 F.3d 1091, 1096 (Fed. Cir. 2020); Amgen Inc. v.

Sanofi, 987 F.3d 1080, 1084 (Fed. Cir. 2021).

[2] In re Wands, 858 F.2d 731 (Fed. Cir. 1988)

[3] See Idenix Pharms. LLC v. Gilead Sciences Inc., 941 F.3d, 1149, 1161 (“Where, as here, working examples are present but are very narrow, despite the wide breadth of the claims at issue, this factor weighs against enablement.”).

[4] MagSil Corp. v. Hitachi Glob. Storage Techs., Inc., 687 F.3d 1377, 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2012)

In two recent opinions, the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) reversed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s (“PTAB”) invalidation of 42 claims across two patents because of the PTAB’s “violat[ion] of a patent owner’s procedural rights” under the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”). In both opinions, the CAFC stated that “the APA imposes particular requirements on the PTO regarding timely notice and the opportunity to respond to matters of fact and law asserted.” But, in neither case did the PTAB give the patent owners proper notice and opportunity to respond to arguments that the PTAB relied on in invalidating their patent claims.

In Oren, a petitioner filed an inter partes review (“IPR”) arguing that U.S. Patent No. 9,403,626 (the ‘626 patent) was obvious in view of the Smith publication (“Smith”). Specifically, the petitioner argued that while Smith did not disclose the exact claim limitation, it would have been designed to meet that limitation because of safety factors that one should consider during manufacture. The PTAB rejected the petitioner’s safety factor argument, but nevertheless, determined that Smith could be modified to meet the claim limitation and found the claims obvious on that basis. The petitioner did not argue that Smith could be modified in its IPR petition. Nor did the PTAB raise the modification theory in its institution decision. Thus, the patent owner did not have an opportunity to address whether Smith could be modified as determined by the PTAB. The CAFC found it improper to invalidate a claim without giving the patent owner an opportunity to address the basis for invalidation. Because the PTAB impermissibly “repurpose[ed] the theory of a motivation to modify” Smith, the CAFC reversed the PTAB’s findings of obviousness.

In Qualcomm, the parties to an IPR agreed to the construction of the claim term “plurality of carrier aggregated transmit signals” such that it required an increased bandwidth. In deeming the contested claims of U.S. Patent No. 9,608,675 (“the ‘675 patent”) obvious, the PTAB construed this term differently such that it did not require an increased bandwidth. Neither party was aware of the PTAB’s adopted construction or had an opportunity to respond to it. Bewildered, the CAFC stated that “it is difficult to imagine either party anticipating that already-interpreted terms were actually moving targets . . . [and] it is unreasonable to expect parties to brief or argue agreed-upon matters of claim construction.” Because the PTAB “failed to provide [the patent owner] adequate notice and opportunity to respond” where the PTAB “diverged from its agreed-upon” claim construction, the CAFC reversed the PTAB’s findings of obviousness.

When reviewing PTAB decisions, patent owners should carefully consider whether their procedural rights have been violated because they have not been given adequate notice or opportunity to respond to the basis relied on by the PTAB. Accordingly, it is important for patent owners to track arguments and claim constructions raised by both the opposition and the PTAB so as to identify any improper invalidating theories that may raise grounds for appeal.