On September 28, 2021, the Federal Circuit, (“CAFC”), reinstated an enhanced damages award against Cisco Systems Inc. (“Cisco”), holding that both substantial evidence supports the jury’s finding of Cisco’s willful infringement after May 8, 2012, and that Cisco’s conduct rises to the level of “wanton, malicious, and bad-faith behavior” required for enhanced damages.

The dispute arose between SRI International (“SRI”) and Cisco over two patents relating to cybersecurity. In 2017, a jury found that Cisco willfully infringed certain claims of SRI’s asserted patents. Based on this willfulness finding, the District Court doubled its damage award and explained that enhancement was appropriate “given Cisco’s litigation conduct, its status as the world’s largest networking company, its apparent disdain for SRI and its business model, and the fact that Cisco lost on all issues during summary judgment and trial, despite its formidable efforts to the contrary.” It also noted that “Cisco pursued litigation about as aggressively as the court has seen in its judicial experience” and that its litigation strategy “created a substantial amount of work for both SRI and the court, much of which work was needlessly repetitive or irrelevant or frivolous.”

Upon first appeal, the CAFC vacated and remanded the ruling, stating “for the time period prior to May 8, 2012, ‘the record is insufficient to establish that Cisco’s conduct rose to the level of wanton, malicious, and bad-faith behavior required for willful infringement.’” It likewise vacated the district court’s enhanced damages award due to being predicated on the finding of willful infringement. On remand, the district court applied the more-stringent willfulness standard described above and held that no willful infringement was present after May 8, 2012. It also noted that “the Court of Appeals is not entirely consistent in its use of adjectives to describe what is required for willfulness.”

Upon second appeal, the CAFC clarified that the language “wanton, malicious, and bad-faith,” refers to conduct warranting enhanced damages and not to conduct warranting a finding of willfulness. Rather, ‘willfulness’ requires a jury to find no more than deliberate or intentional infringement. Consequently, the CAFC held that substantial evidence supported the jury’s willful infringement finding for the time period after May 8, 2012 based on Cisco’s lack of reasonable bases for its infringement and invalidity defenses and the jury’s unchallenged induced infringement findings.

Additionally, the CAFC clarified that although willfulness is a component of enhancement, “an award of enhanced damages does not necessarily flow from a willfulness finding.” Further, discretion remains with the district court to determine sufficiently egregious conduct warranting enhanced damages. Consequently, the CAFC discerned no abuse in discretion in the district court awarding double damages above and found that the district court appropriately considered factors warranting enhanced damages beyond willfulness including “the infringer’s behavior as a party to the litigation,” the infringer’s “size and financial condition,” the infringer’s “motivation for harm,” and the “closeness of the case.”

This case clarifies that the standards for willfulness are distinct from the standard for enhanced damages. Further, the enhanced damages inquiry may take into consideration a wide variety of behavior, including trial conduct and unreasonably aggressive litigation tactics.

On August 23, 2021, the 9th Circuit found that under California common law and statutory copyright law, owners of pre-1972 sound recordings do not have an exclusive ownership right in public performances. This holding means that owners of pre-1972 sound recordings are entitled only to royalties for the public performance of their sound recordings under the federal Music Modernization Act (“MMA”).

In a class action suit against Sirius XM, Plaintiffs argued that under California common law and statutory copyright law, Plaintiffs hold the exclusive ownership right of public performance, and therefore Sirius XM must pay for the broadcast of its pre-1972 songs. As a preliminary issue, the 9th Circuit found that the MMA does not preempt the claims made in this case because Sirius XM did not meet “certain conditions” that are required for the MMA to preempt state law claims arising before the passage of the MMA.

This case follows recent decisions in New York and Florida where no exclusive right to public performance was found under each state’s respective common law. The New York Court of Appeals, hearing a certified question from the 2nd Circuit that is parallel to this case, found that “common-law copyright protection prevents only the unauthorized reproduction of the copyrighted work,” but a lawful purchaser can play copies of the work. Flo & Eddie, Inc., 70 N.E.3d 936, 947 (N.Y. 2016). Similarly, in Flo & Eddie, Inc. v. Sirius XM Radio Inc., 229 So. 3d 305, 307 (Fla. 2017), on certification from the 11th Circuit, the Florida Supreme Court found that there is no common law public performance right.

In contrast, the California district court had concluded that under Section 980(a)(2) of the California Civil Code, “exclusive ownership” included the right of public performance. In determining the rights covered under this term, the court referred to the individual dictionary definitions of the words “exclusive” and “ownership,” while reasoning that because the California legislature only listed one exception, for those who make cover versions of songs, courts should infer that the legislature “included all exceptions it intended to create.” The 9th Circuit, however, found that the district court erred when it held that “exclusive ownership” included the right to public performance because the common law meaning of “exclusive ownership” must be examined under the historical setting of 1872, when the copyright statute was first enacted. As of 1872, no California court recognized the right of public performance, and by 1937, only Pennsylvania’s state supreme court held that its common law protected an exclusive performance right. Therefore, in the state copyright law context, “exclusive ownership,” only refers to the owner’s common law copyright in an unpublished work to reproduce and sell copies. Fortunately, the MMA provides owners of many pre-1972 sound recordings with public performance rights for a period of time.

Covers select developments in patent and trade secret law between 2014 and 2016, including changes to the standard of patentability and patent infringement damages, as well as the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act.

On September 23, 2021, the Third Circuit reversed dismissal of a newscaster’s statutory Pennsylvania Right of Publicity claim. It held that there was no immunity under the Communications Decency Act (“CDA”) for said claim because the CDA’s carve out for intellectual property protections are not limited to federal intellectual property laws, but can include state laws protecting intellectual property too (a.k.a. publicity rights). On the other hand, on September 27, 2021, the Eastern District of Michigan (“the District Court”) dismissed a complaint based on the unauthorized use of the name of deceased fashion icon Frankie Edith Kerouac Parker, a.k.a. “Edie Parker.” The district court determined that the Estate’s Michigan right of publicity common law rights were preempted by the Heyman’s federal trademark rights.

In the Third Circuit case, Karen Hepp, a newscaster, alleged that she had built an “excellent reputation as a moral and upstanding community leader” and amassed a large social media following such that her endorsements were valuable. She sued Facebook (and others) when she noticed her photo being used without her permission on Facebook to promote a dating app called FirstMet. The Eastern District of Pennsylvania dismissed Hepp’s claims under Section 230 of the CDA, which immunizes websites from liability for content that is posted by others.

However, CDA Section 230 does not bar intellectual property claims against websites. Relying on Ninth Circuit precedent, Facebook argued that the “intellectual property” under the CDA meant only federal intellectual property laws. The Third Circuit disagreed and held that a state law can be a “law pertaining to intellectual property” too. The Third Circuit then reviewed the Pennsylvania right of publicity statute, found that it was analogous to a trademark law, and therefore outside of the CDA’s immunity. The Third Circuit expressed no opinion as to whether other states’ rights of publicity also qualified.

Turning to the District Court case, Edie Parker, first wife of writer Jack Kerouac and fashion icon became a celebrity in the 1950s and 1960s. Brett Heyman, a fan of Edie Parker, named her daughter Edie Parker, then started a handbag company named Edie Parker LLC without obtaining permission from the original Edie Parker’s Estate. Heyman’s Edie Parker, LLC has made tens of millions of dollars selling handbags and other products emulating Edie Parker’s style. Moran, the Personal Representative of Edie Parker’s Estate brought suit for unauthorized commercial use of the name “Edie Parker.” Heyman filed a motion to dismiss in which she asked the court to take judicial notice of her eight federal trademark registrations for EDIE PARKER and argued that the Lanham Act preempted the Estate’s Michigan common law right of publicity claim.

The Court recognized that the right of publicity protects a pecuniary interest in the commercial exploitation of an individual’s identity and that such unauthorized use of that name or likeness is actionable even after an individual’s demise. Nevertheless, the Court granted the motion to dismiss based on Heyman’s preemption argument. This case appears to be the first time that a federal court has preempted a state right of publicity claim based on federal trademark registration under the Lanham Act.

On September 9, 2021, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) found that use of a catalog description of a prior art product as a prior art reference in an IPR proceeding does not create 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2) estoppel as to the underlying prior art product. Further, the CAFC denied mandamus because DMF, Inc. (“DMF”) failed to show that a post-judgment appeal is an inadequate remedy for asserting a statutory estoppel argument or that it had a “clear and indisputable” right to relief.

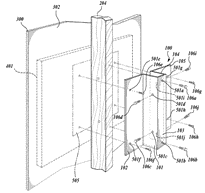

DMF is the owner of U.S. Pat. No. 9,964,255 (the “patent-in-suit”), which is directed to certain compact recessed lighting products. DMF sued AMP Plus, Inc., d/b/a Elco Lighting (“Elco”) in the Central District of California, alleging Elco infringed various claims of the patent-in-suit. Elco filed an inter partesreview (IPR) petition[1] arguing that the claims were invalid based on a product catalogue featuring a Hatteras lighting product (“Hatteras catalog”). DMF argued that the claims were non-obvious because Elco “mixed and matched” various products from the catalog. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) agreed with DMF and found the claims non-obvious. The case reverted to the district court and DMF moved, under § 315(e)(2), to bar Elco from asserting invalidity based on the actual Hatteras product. Section 315(e)(2) provides that the “petitioner in an inter partesreview of a claim in a patent … may not assert … in a civil action … that the claim is invalid on any ground that the petitioner … reasonably could have raised during the inter partes review.” The district court’s evaluation focused on whether differences that were “germane to the invalidity dispute” existed between the Hatteras product and its catalog description. The district court found the Hatteras product to be substantively different; specifically, the court pointed to DMF’s prior argument that Elco “mixed and matched” various products in the catalog, and that the description within the Hatteras catalogue failed to disclose all of the product’s features. DMF then petitioned the CAFC for a writ of mandamus challenging the ruling that Elco was not statutorily estopped from raising this particular ground of invalidity.

DMF is the owner of U.S. Pat. No. 9,964,255 (the “patent-in-suit”), which is directed to certain compact recessed lighting products. DMF sued AMP Plus, Inc., d/b/a Elco Lighting (“Elco”) in the Central District of California, alleging Elco infringed various claims of the patent-in-suit. Elco filed an inter partesreview (IPR) petition[1] arguing that the claims were invalid based on a product catalogue featuring a Hatteras lighting product (“Hatteras catalog”). DMF argued that the claims were non-obvious because Elco “mixed and matched” various products from the catalog. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) agreed with DMF and found the claims non-obvious. The case reverted to the district court and DMF moved, under § 315(e)(2), to bar Elco from asserting invalidity based on the actual Hatteras product. Section 315(e)(2) provides that the “petitioner in an inter partesreview of a claim in a patent … may not assert … in a civil action … that the claim is invalid on any ground that the petitioner … reasonably could have raised during the inter partes review.” The district court’s evaluation focused on whether differences that were “germane to the invalidity dispute” existed between the Hatteras product and its catalog description. The district court found the Hatteras product to be substantively different; specifically, the court pointed to DMF’s prior argument that Elco “mixed and matched” various products in the catalog, and that the description within the Hatteras catalogue failed to disclose all of the product’s features. DMF then petitioned the CAFC for a writ of mandamus challenging the ruling that Elco was not statutorily estopped from raising this particular ground of invalidity.

Regarding mandamus, the CAFC noted that it is “reserved for extraordinary situations.” Gulfstream Aerospace Corp. v. Mayacamas Corp., 485 U.S. 271, 289 (1988). Under the All Writs Act, the CAFC may issue a writ if: (1) there is no other method of obtaining relief; (2) they have a “clear and indisputable legal right;” and (3) a “writ is appropriate under the circumstances.” Here, the CAFC denied mandamus because DMF was unable to demonstrate that a “post-judgment appeal is an inadequate remedy” and had not met its “heavy burden” of showing the district court’s ruling was “clearly and indisputably erroneous.”

Although non-precedential, this case is important because it limits the scope of the statutory estoppel associated with seeking IPR before the PTAB; acknowledges that there can be a difference between a publication disclosing a prior art product and the product, itself; and reminds us of the limited nature of mandamus.

[1] An IPR petitioner may seek to invalidate claims based on “prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.” 35 U.S.C. § 311(b).

On September 8, 2021, the Federal Circuit, (“CAFC”), found that the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s (“PTAB”) decision to institute inter partes review (“IPR”) of four MaxPower patents, despite an agreement to arbitrate disputes regarding those patents, was unappealable. The CAFC also denied granting a writ of mandamus to stay or terminate the IPRs.

The dispute arose between ROHM Semiconductor (“ROHM”) and MaxPower Semiconductor (“MaxPower”) over four patents relating to semiconductors. In 2007, ROHM and MaxPower entered into a technology licensing agreement (“TLA”) allegedly covering the four patents, which included an agreement to arbitrate “[a]ny dispute, controversy, or claim arising out of or in relation to this Agreement or at law, or the breach, termination, or validity thereof.” Ultimately, by 2019, disputes arose between ROHM and MaxPower regarding whether the TLA covered ROHM’s products. In early September 2020, MaxPower notified ROHM of its intent to initiate arbitration. On September 23, 2020, ROHM filed (1) a declaratory judgment of noninfringement of the four MaxPower patents, and (2) four IPR petitions on the same four patents. While the district court promptly dismissed ROHM’s declaratory judgment action, stating that the TLA “unmistakably delegate[s] the question of arbitrability to the arbitrator,” the PTAB instituted ROHM’s petitions, finding “the arbitration clause is not a reason to decline institution.”

The CAFC began by citing to 35 U.S.C. § 314(d), which states that “[t]he determination by the Director whether to instate an [IPR] under this section shall be final and nonappealable.” The majority then rejected MaxPower’s argument regarding the collateral estoppel doctrine because MaxPower would have the opportunity to raise its arbitration-related challenges after the PTAB decides the IPRs. The majority then stated that the permissible appeals enumerated in 9 U.S.C. § 16(a)(1) did not apply to the PTAB’s decision to institute IPRs. Finally, the majority stated that (1) MaxPower failed to meet its burden of meeting the “demanding standards for mandamus,” (2) the “Board is not bound by the private contract between MaxPower and ROHM,” and (3) 35 U.S.C. § 294 “does not by its terms task the agency with enforcing private arbitration agreements.”

However, the dissent noted that Congress intended for agreements to arbitrate patent validity to be “valid, irrevocable, and enforceable” under 35 U.S.C. § 294 and that the majority opinion would add “a new caveat to Congress’s clear instruction” regarding arbitration with respect to IPRs. Such an exception runs afoul of the “strong policy favoring arbitration repeatedly confirmed by the Supreme Court.” Accordingly, the dissent believed that the PTAB needed to only “defer to the arbitration agreement by staying or terminating its own proceedings until the arbitration issue is resolved,” and the majority and PTAB instead permitted ROHM to “escape resolution in an arbitral forum.”

Although non-precedential, this decision is important because it permits parties to circumvent agreements to arbitrate regarding patent validity by seeking an IPR. While the majority does not foreclose an appeal on arbitrability of the issue after the PTAB’s decisions, this decision may permit the first step to weakening strong policies favoring arbitration. Additionally, although not directly addressed by the CAFC, a party avoiding arbitration in this manner may open itself up to a claim of breach of the arbitration agreement in a separate action.

Artificial Intelligence (“AI”) has come a long way in recent years and has allowed people to automate many tasks, but one task AI cannot do is be a named inventor on a patent, at least not yet. Stephen Thaler tried to file a patent application naming his AI machine as an inventor, but the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) would not let him. In filing his patent application, Thaler identified the inventor’s “given name” as the name of his AI machine “DABUS” and under “family name” wrote “[i]nvention generated by artificial intelligence.” The USPTO required Thaler to amend the inventorship to a natural person, explaining that the statutory language that Congress has used to define the term “individual” and “himself or herself” was reserved for human beings. Because the USPTO failed to process the patent application as long as Thaler kept his AI machine as the named inventor, Thaler filed suit against the USPTO in the Eastern District of Virginia seeking a reversal of that decision and a declaration from the court that a patent application for an AI-generated invention should not be rejected on the basis that no natural person is identified as the inventor.

The USPTO moved for summary judgment, arguing that its interpretation of the Patent Act is entitled to deference under the Supreme Court precedent. Thaler argued that the USPTO was not entitled to deference because the USPTO did not perform certain actions, such as consider alternative interpretations or provide any evidence that Congress intended to exclude AI-generated inventions from patentability. The court rejected Thaler’s argument because it would add requirements that were counter to past precedence, and subsequently gave the USPTO’s interpretation, that an “inventor” must be a natural person, deference.

Even without deference, the court found that the USPTO’s conclusion was correct under the law of statutory construction, wherein the plain language of the statute controls. 35 U.S.C. § 100(f) provides that “[t]he term ‘inventor’ means the individual . . . who invented or discovered the subject matter of the invention.” Thaler did not present any evidence that Congress intended to deviate from the typical use of the term “individual.” Thaler attempted to argue that policy considerations of encouraging innovation dictate that AI-based inventions should be patentable, but the court denied this argument because Thaler did not provide support that these policy considerations should override the plain meaning of a statutory term.

Thus, the court granted the USPTO’s motion for summary judgment, answering the core issue of whether AI can be named as an “inventor” by stating that, “[b]ased on the plain statutory language of the Patent Act and Federal Circuit authority, the clear answer is no.” The court, however, acknowledged that, “[a]s technology evolves, there may come a time when artificial intelligence reaches a level of sophistication such that it might satisfy accepted meanings of inventorship.” So, while an AI machine cannot be named as an inventor under the current statutory framework, the debate continues as to whether the Patent Act should be amended to allow inventions by AI machines.

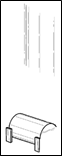

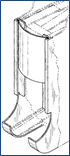

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”) recently held, again, that the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) erred in finding U.S. Design Patent Nos. D612,646 and D621,645, directed to gravity feed soup can dispensers, not obvious. The decision underscores that design patents are subject to the same rules as utility patents for objective indicia of non-obviousness.

In the first appeal, the CAFC reversed the PTAB’s disqualification of Petitioner’s primary reference. The PTAB had erred by focusing on “ever-so-slight differences in design” (lack of a “cylindrical object” and differences in the label area) instead of evaluating differences “in light of the overall similarities.”[1] On remand, the PTAB acknowledged that the prior art (right) disclosed a design not just basically the same, but having the same overall appearance as that claimed (left). Regardless, the PTAB again found the patent non-obvious this time based on objective indicia of non-obviousness: industry praise by the Petitioner; commercial success; and copying by others.

In this second appeal, the CAFC found that the PTAB’s approach was legally and factually flawed.[2] First, the CAFC faulted the PTAB for presuming a nexus between the claimed design and the objective indicia even though the patent did not even claim an entire product. To presume a nexus, the patented design must be “coextensive” with the successful or praised product—the product must be the invention itself. However, the successful product comprised substantial unclaimed, often functional portions, such as the rails and sides of the product. The Board dismissed these missing elements as “insignificant to the ornamental design.” That may be true, but as the CAFC noted, “ornamental significance” is not the question in determining coextensiveness; the unclaimed portions are still “significant functional elements,” and thus, the CAFC held that “no reasonable trier of fact could find that the [product] is coextensive with the claimed design.”

The CAFC further reversed the PTAB’s finding of a nexus-in-fact based on the design’s claimed label area. To establish a nexus-in-fact for objective indicia of non-obviousness, the patent owner must show that the indicia are “the direct result of the unique characteristics of the claimed invention” and not of features “known in the prior art.”[3] However, the large label area was not “unique” to the patented design, it was disclosed by the asserted prior art, and the specific dimensions in which it might differ were unclaimed or unsubstantiated. The PTAB had tried to distinguish the required showing of nexus for design patents from utility patents on the basis that design patent obviousness contemplates overall visual appearance of the claimed design as a whole. The CAFC rejected this distinction because obviousness in the utility patent context similarly evaluates the claimed invention as a whole, yet indicia must still be linked to particular features.

[1] Campbell Soup Co. v. Gamon Plus, Inc., 939 F.3d 1335, 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2019)

[2] Fox Factory, Inc. v. SRAM, LLC, 944 F.3d 1366, 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2019)

[3] Fox Factory v. SRAM, 944 F.3d 1366, 1373-74 (Fed. Cir. 2019); Ormco v. Align Tech., 463 F.3d 1299, 1312 (Fed. Cir. 2006)

Irwin IP is very pleased to welcome Alexa Tipton as Special Counsel. Alexa Tipton will be working as special counsel for entertainment law and pro bono services at Irwin IP. Alexa graduated from University of Notre Dame Law School, and prior to joining Irwin IP she interned at Lawyers for the Creative Arts, a nonprofit organization that provides pro bono legal assistance to artists in the Chicago area, where she worked alongside artists to identify their relevant legal issues for pairing with appropriate legal representation. In addition, Alexa interned for Judge Derek Meinecke at the 44th District Court in Royal Oak, Michigan. We’re very excited to have her join the team!

Irwin IP is very pleased to welcome Alexa Tipton as Special Counsel. Alexa Tipton will be working as special counsel for entertainment law and pro bono services at Irwin IP. Alexa graduated from University of Notre Dame Law School, and prior to joining Irwin IP she interned at Lawyers for the Creative Arts, a nonprofit organization that provides pro bono legal assistance to artists in the Chicago area, where she worked alongside artists to identify their relevant legal issues for pairing with appropriate legal representation. In addition, Alexa interned for Judge Derek Meinecke at the 44th District Court in Royal Oak, Michigan. We’re very excited to have her join the team!