Irwin IP is pleased to welcome Nanet Manieri to the team! Nanet is an executive assistant at Irwin IP LLC since May 2022. She will work closely with and assist the CEO and Director of Professional and Business Development, while also handling other administrative tasks. We are excited to have Nanet join our Team!

While a website owner may not want competitors scraping information from their system, it may not be a violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (“CFAA”) unless the website owner has “gates-up.” The Ninth Circuit recently upheld a preliminary injunction preventing LinkedIn Corp (“LinkedIn”) from denying hiQ Labs, Inc. (“hiQ”) access to publicly available information on LinkedIn member profiles.

LinkedIn, a professional networking site, permits users to create profiles with their personal professional information. Using automated bots, hiQ, a data analytics company, scraped information from public LinkedIn profiles which it then used to create “people analytics” to sell to business clients. In May 2017, LinkedIn sent hiQ a cease-and-desist letter. In return, hiQ asserted its right to access LinkedIn’s public pages and filed an action seeking injunctive relief and a declaratory judgment that LinkedIn, among other things, could not invoke the CFAA, which prohibits a person from accessing a “protected computer” without authorization.

The district court found in favor of hiQ, granting a preliminary injunction and ordering LinkedIn to remove technical barriers to hiQ’s access of public profiles. LinkedIn asserted that hiQ had violated the CFAA once it received a cease-and-desist letter from LinkedIn because it continued scraping LinkedIn’s data. LinkedIn appealed and the Ninth Circuit affirmed the preliminary injunction. The Supreme Court granted certiorari, vacated the judgment, and remanded for further consideration in light of Van Buren v. United States, 141 S. Ct. 1648 (2021), which held that the CFAA “covers those who obtain information from particular areas in the computer . . . to which their computer access does not extend” and does not cover “information that is otherwise available to them.”

On remand, finding that Van Buren reinforced its interpretation of the CFAA, the Ninth Circuit reaffirmed the district court’s granting of the preliminary injunction. LinkedIn could not prevent hiQ from collecting and using information that LinkedIn users had shared on their public profiles because LinkedIn did not have its “gates-up” such that an authorization was required to access that information. Instead, LinkedIn profiles contained information that was available for viewing by anyone with a web browser. Further, the Ninth Circuit found that hiQ’s actions were not “without authorization” because that statutory language was limited to “when a person circumvents a computer’s generally applicable rules regarding access permissions” rather than a contract-based interpretation.

This case demonstrates that, if a company does not have its “gates-up” such that there are no restrictions to accessing information, then that company likely cannot bring a CFAA claim against another if it is using publicly available data on that company’s website. Therefore, in order to ensure that a CFAA claim is available, that company’s information must be password protected or restricted in a way that information is not otherwise publicly available.

In a decision designated precedential on March 29, the USPTO refused to grant Jasmin Larian trade dress protection for her popular handbag design because the design was generic and nondistinctive. But, the USPTO granted somebody else a design patent claiming that same bag design on an application filed months after Larian’s trade dress application. It did so even though the law requires design patents to be novel and non-obvious but does not require the same of trade dress. So, how did that even happen?

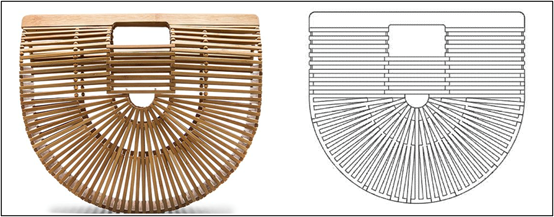

In July 2017, Larian filed her trade dress application for the “Ark” bag (a structured, bamboo handbag) (left [1]) produced under her designer brand, Cult Gaia. About four months later, Minling Lin (if such a person exists) applied for a design patent on an identical handbag design (right), which the USPTO issued on March 19, 2019.

However, in January of 2022, the USPTO refused Larian’s trade dress registration, finding it generic and lacking both intrinsic and acquired distinctiveness. A product design may be found generic when it is so common that it does not identify any particular source. The TTAB’s main evidence of genericness was that decades before when Cult Gaia started selling the Ark, and even concurrently, similar handbags were sold in the U.S. and abroad by other producers. The TTAB also found that the Ark had not acquired distinctiveness, meaning consumers had not started associating the Ark with Cult Gaia, for similar reasons.

Larian argued that because trade dress is not required to be novel, the Ark could still function as trade dress in the U.S. even if similar designs existed for decades and in other countries. The TTAB agreed that novelty is not a requirement for trade dress, but still found the Ark did not identify Cult Gaia as the source. Thus, the USPTO maintained its refusal to register the Ark as Cult Gaia’s trade dress.

It is strange that, notwithstanding the patent laws’ requirements of novelty and originality, the USPTO issued the interloper, Minling Lin, a design patent on a wildly popular handbag design, but refused the bona fide designer even trade dress protection. Lack of any meaningful examination seems the clearest explanation. But, given the cost of putting even a clearly invalid patent out of its misery, this highlights a glaring vulnerability of the United States’ design patent regime to gamesmanship and abuse.

[1] “Trade Dress and Patents and Trolling(?), Oh My: Everyone Wants a Piece of this Traditional Japanese Bag,” The Fashion Law, [Hyperlink] (accessed April 20, 2022).

The United States District Court for the Northern District of California (“the Court”) recently granted Google’s motion to dismiss Sonos’ claims for willful and indirect infringement for insufficient pleading. In doing so, the Court made the unusual move of sua sponte certifying its decision for interlocutory review.

Regarding willful and indirect infringement, district courts have disagreed as to what needs to be pled. Here, the Court recognized that a claim for both willful and indirect infringement must plead the alleged infringer’s knowledge of the patent, knowledge of infringement, and specific intent to infringe. The Court then held that pleading willful infringement does not require any further showing, such as egregious behavior. While egregious behavior, which some district courts have required for willful infringement, is a requirement for enhanced damages, that determination is made at the end of the case and may include consideration of litigation conduct. The question of adequate pleading of willful infringement occurs at the outset of the case so it would not be appropriate to consider egregiousness.

Using that standard, the Court analyzed the willful and indirect infringement claims and found them insufficient. In doing so, the Court acknowledged another dispute between district courts as to whether the complaint can provide notice of the patents and of the infringement. In general, this Court agreed with the district courts that have found a complaint cannot provide adequate notice of the patent and the infringement to support a claim of willful and indirect infringement. Furthermore, any pre-suit notice must allow enough time for a party to evaluate the claims and cease any activity and/or seek a license. Twenty-four-hour notice, as provided here, was not sufficient time and, hence, the Court dismissed the claims of willful and indirect infringement without prejudice. The Court, however, did note that it would allow discovery into Google’s pre-suit knowledge of the patents and infringement and would allow Sonos leave to file an amended claim adding willful and indirect infringement if it discovered sufficient pre-suit knowledge of the patent and of the infringement.

Interestingly, there was also an accompanying declaratory judgment action. For a declaratory judgment action, the Court was of the view that the complaint should provide adequate notice because the declarant must have had knowledge of the patent and considered infringement before filing such an action. Therefore, in the declaratory judgment action, Sonos would be able to file a counterclaim of willful and indirect infringement.

And in a rare move, the Court sua sponte certified its order for an interlocutory appeal noting “that reasonable minds may differ as to the ground rules set forth above for pleading willfulness and [the knowledge requirement for] indirect infringement … and recognizing the vast amount of resources being consumed in the district courts over such pleading issues.” While the Federal Circuit recently reversed a district court that overruled a jury verdict of willful infringement because there was no egregious behavior, the Federal Circuit has yet to address the proper pleading standards for willful and indirect infringement, and in particular, whether a complaint can provide adequate notice to support such a claim. The split between district courts regarding this issue is well known. Hopefully, the Court’s certification of its order for an interlocutory appeal will finally prompt the Federal Circuit to resolve this split and provide clarity on the proper standard for pleading willful and indirect infringement.

In a trademark infringement dispute between Bluetooth and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (“FCA”), the Ninth Circuit vacated the District Court for the Western District of Washington’s order granting partial summary judgment that the first sale doctrine did not apply to the Bluetooth’s trademark claims. Instead, the Ninth Circuit found that the first sale doctrine applies to component parts embedded in a new, downstream product and remanded the district court’s grant for further proceedings.

The case arose out of FCA’s use of Bluetooth’s trademarks and logos on FCA’s websites and in-vehicle displays called “head units.” FCA’s use of the marks extended across its Fiat, Chrysler, Dodge, Jeep, and Ram brands. Generally, rightful users of the Bluetooth marks must join Bluetooth’s “Special Interest Group” (“SIG”), where members of the SIG are required to (1) execute licensing agreements, (2) submit declarations of compliance, and (3) pay royalties. Here, FCA bought head units, which bore Bluetooth’s marks, manufactured by SIG-approved third parties. Bluetooth then brought trademark claims against FCA, and FCA raised numerous defenses, including the first sale doctrine. On cross-motions for summary judgment, The District Court rejected the first sale defense, reasoning that FCA’s conduct went beyond “stocking, displaying, and reselling a producer’s product,” which precedent has found does not constitute infringing behavior.

Under the first sale doctrine, “with certain well-defined exceptions, the right of a producer to control the distribution of its trademarked product does not extend beyond the first sale of the product.” Indeed, a producer or registrant’s trademark rights are “exhausted as to a given item upon the first authorized sale of that item.” The Ninth Circuit found that the District Court’s reading of the first sale doctrine was too “narrow.” While the District Court cited to Sebastian Int’l. v. Longs Drug Stores Corp., claiming that FCA did more than just “stock, display, and resell a producer’s product,” the Ninth Circuit found that Sebastian did not actually articulate the outer bounds of the applicability of first sale doctrine. Instead, the Ninth Circuit found FCA’s activities to be more akin to a 1924 Supreme Court case Prestonettes, Inc. v. Coty, in which a cosmetics manufacturer that purchased a trademark-protected powder, “subject[ed] it to pressure, add[ed] a binder to give it coherence and s[old] the compact in a metal case.” Accordingly, the Ninth Circuit found that where a vehicle manufacturer purchases a component part bearing registered marks from a licensed manufacturer, and incorporates it into a new, downstream product, the first sale doctrine applies and can be a viable defense to claims of trademark infringement. Notwithstanding the win in the Ninth Circuit, FCA is not paired with Bluetooth quite yet. Because the first sale doctrine is “generally focused on the likelihood of confusion among consumers,” a key issue remaining to decide whether FCA’s defense will be successful is “whether FCA had adequately disclosed its relationship with, and qualification to use, Bluetooth technology.” On remand, the district court will decide the “fact-intensive” issue.

Irwin IP is excited to announce our move to 150 N. Wacker! We have taken over the 7th floor and are enjoying our river views.

We continue to grow faster than we imagined and are delighted to be able to provide a top-of-the-line workspace for our employees to flourish.

We thank all our clients, colleagues and friends for their support, and our attorneys and support staff for all the excellent client service, that helped us grow

The instant appeal stems from a dispute between Complainant Broadcom Corporation (“Broadcom”) and Respondents Renesas Electronics Corporation and Renesas Electronics America, Inc., among other respondents, in a 19 U.S.C. § 1337 (“Section 337”) Investigation at the International Trade Commission (“the Commission”) involving U.S. Patent No. 7,437,583 (“the ‘583 patent”), among other patents. In a final initial determination, the administrative law judge (“the ALJ”) held, inter alia, that Broadcom did not satisfy the technical prong of the domestic industry because the Broadcom system-on-a-chip (“SoC”) product used to establish a domestic industry did not include a “clock tree driver,” one of the limitations of claim 25 of the ‘583 patent. The Commission affirmed the ALJ’s holding, and both parties appealed. One of the issues raised on appeal was Broadcom’s challenge of the ruling that there was no Section 337 violation of the ‘583 patent due to Broadcom’s failure to satisfy the technical prong of the domestic industry.

To meet the technical prong of the domestic industry requirement, the Complainant must establish that it practices at least one claim of the asserted patent. Microsoft Corp. v. ITC, 731 F.3d 1354, 1361–62 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (citing 19 U.S.C. § 1337(a)(2)–(a)(3)). This requires a Complainant to identify “actual ‘articles protected by the patent.’” Id. at 1361.

The ALJ found that Broadcom’s SoC did not contain the “clock tree driver” required by claim 25 of the ‘583 patent because the driver must be stored on an external memory that is separate from the SoC. Broadcom argued that it integrates its SoC with the external memory to enable retrieval and execution of the “clock tree driver” with the help of its customers. The ALJ did not find that argument persuasive and noted that an “actual article” protected by the patent is needed to meet the technical prong. In affirming the ALJ’s findings, the Commission further stated that, without identifying an actual integration of the SoC and the “clock tree driver,” Broadcom contemplated only a hypothetical device that did not meet claim 25’s limitations, failing to satisfy the technical prong of the domestic industry.

The CAFC affirmed the Commission’s finding, reasoning that Broadcom did not “show that there is a domestic industry product that actually practices” at least one claim of the asserted patent. Id. at 1361. More specifically, Broadcom failed to identify any specific integration of the domestic industry SoC and the “clock tree driver” firmware, or a specific location where the firmware was stored. Unlike in the District Court proceedings, an ITC Complainant must show that it practices the asserted patent(s), so ensuring that there is an “actual article” before the filing of the Complaint is essential.

The remaining open question is whether Broadcom’s argument that it manufactured and tested a “system” that included the SoC and firmware having the clock tree driver would have constituted an “actual article.” This argument was deemed waived because Broadcom did not raise it during the ALJ proceedings, reinforcing the importance of preserving issues for appeal.

Irwin IP is pleased to welcome Marisol Jaimes to the team. Marisol joins us as a Project Assistant and will work collaboratively with the paralegal team and provide administrative support to the attorney teams. We are excited to have Marisol join our Team!

Holding all claims related to homemade bread failed as a matter of law, the 10th Circuit upheld summary judgment of no trade dress infringement and reversed verdicts for misappropriation and false advertising.

Grandma Sycamore’s Home-Made Bread started tantalizing taste buds in Utah in 1979. Leland Sycamore created the recipe, transferred rights to an intermediary in 1998, and Bimbo Bakeries USA, Inc. (“Bimbo”) acquired the business in 2014. Hostess competed by offering Grandma Emilie’s bread, which Oregon-based U.S. Bakery later acquired. Initially, U.S. Bakery produced Grandma Emilie’s in Salt Lake City, having hired a Sycamore follow-on bakery for assistance. But U.S. Bakery moved its operations from Utah to Idaho, bringing along the former Sycamore employee, with plans for a new formula. U.S. Bakery marketed Grandma Emilie’s bread – in both where it operated bakeries and those where it did not – with the tagline “Fresh. Local. Quality.” Bimbo asserted Lanham Act trade dress infringement and false advertising against U.S. Bakery, and trade secret misappropriation under Utah state law. The district court granted summary judgment of no infringement for U.S. Bakery, concluding Bimbo’s trade dress was generic. A jury found for Bimbo on the other claims, entering a misappropriation verdict for $2.1M with additur of $789K for willfulness and awarding $8.0M in false advertising damages with remittitur to $83K.

The 10th Circuit agreed with the district court’s conclusion that Bimbo’s pled trade dress was so broadly claimed as to be generic, and thus there was no trade dress infringement. In its amended complaint, Bimbo identified its bread packaging as consisting of a horizontal label; a design at the top center of the end; the word ‘White’ in red letters; a red, yellow, and white color scheme; and italicized font below the design, outlined in white. U.S. Bakery offered evidence that such trade dress was “the custom in the industry” and Bimbo failed to present facts opposing industry custom trade dress. Addressing misappropriation, the 10th Circuit focused its inquiry on the plaintiff’s burden to show that the purported compilation secret was not generally known or readily ascertainable based on a defendant’s knowledge and experience. Although the opinion redacts the composition recipe, the court’s conclusion that no reasonable jury could find the standard met supports the inference that the bread formulation was none too complex. Despite employee overlap, the standard for a secret was determinative. Finally, reversing false advertising based on “Fresh. Local. Quality”, the court determined that locality is fundamentally subjective and thus unactionable. “Local,” contrary to Bimbo’s argument, did not mean “locally baked.”

In closing, the 10th Circuit noted that “[w]e do not doubt that Bimbo Bakeries has both a protectable trade secret and a protectable trade dress in every loaf of Grandma Sycamore’s. But the versions it tried to claim in this litigation are far too broad to be protectable.” This case is a cautionary tale for rights holders: precisely delineate your trade dress and trade secrets lest, in reaching too far, no protection remains..

On March 10, 2022, the Ninth Circuit (“the court”) held that the similarities between the ostinatos (the repeating musical phrases) of the songs “Joyful Noise” from Christian hip-hop artists Marcus Gray, Emanuel Lamber, and Chike Ojukwu (collectively “Gray”) and “Dark Horse” by Katheryn Hudson (“Katy Perry”) were not protectible under copyright law as the copied ostinato was merely a chord progression.

On March 10, 2022, the Ninth Circuit (“the court”) held that the similarities between the ostinatos (the repeating musical phrases) of the songs “Joyful Noise” from Christian hip-hop artists Marcus Gray, Emanuel Lamber, and Chike Ojukwu (collectively “Gray”) and “Dark Horse” by Katheryn Hudson (“Katy Perry”) were not original expressions and therefore were not protectible under copyright law.

Gray sued Katy Perry for copyright infringement relating to Perry’s hit song “Dark Horse.” Gray claimed Perry copied an ostinato—specifically, a series of eight notes (sixteen when combined)—from their song “Joyful Noise.” The two ostinatos differed in the last two notes, but relied on a uniform rhythm. A jury found Perry liable for infringement and awarded Gray $2.8 million in damages. After the trial, Perry moved for judgment as a matter of law or, alternatively, a new trial. The district court vacated the judgment as a matter of law finding that none of the identified individual points of similarity between the two ostinatos—such as the length, rhythm, melodic content, melodic shape, quality and color of the sound, or the placement of the ostinato in the musical space—either alone or in combination, constituted a copyrightable original expression. Gray appealed to the Ninth Circuit.

On appeal, the court addressed the threshold issue of what is a copyrightable original expression. The court noted “copyright protection extends only to works that possess…some minimal degree of creativity.” Gray was required to show Perry had (1) access to Joyful Noise and (2) both ostinatos were substantially similar. The court focused on the second prong, which mandates that Gray satisfy both the extrinsic and intrinsic tests of copying. The extrinsic test requires parties to distinguish between protected and unprotected material in a work. The court focused only on the extrinsic test as it can be resolved as a matter of law while the intrinsic test examines substantial similarity from the viewpoint of an ordinary observer and is usually left to the factfinder. The court applied the extrinsic analysis to each proposed similarity to determine which aspects of Joyful Noise’s ostinato, if anything, qualified as an original expression. The court stated that copyright law has a “famously low bar for originality” but that “copyright does require at least a modicum of creativity” and does not protect “ common or trite musical elements, or commonplace elements that are firmly rooted in the genre’s tradition.”

The court held that each point of similarity identified by Gray between the two ostinatos was not a protectible form of expression. The court noted that the playing of eight notes, even in rhythm, is a “trite” musical choice that is unprotectible. Next, the court found the texture of the ostinato or how the different musical elements are mixed together, and the melodic shape was too abstract for protection. Thereafter, the court held that the timbre or sound quality of the ostinatos through the use of synthesizers was not protectible. The court then found that the eight-note pitch sequence was not copyrightable even as a component of a protectible melody which the court noted is consistent with current caselaw finding that chord progressions cannot be individually protected as they are basic musical building blocks. Next, the court examined the components of the ostinato as a combination and found that the ostinato only employed a conventional arrangement of musical building blocks and could not be protected.

This decision is sure to impact enforcement efforts for copyrights of musical works. Parties will be emboldened to argue note sequences in a musical work are not original and, thus, not copyrightable.