While it is accepted that filing an amended complaint supersedes the original complaint rendering it without legal effect, a defendant may waive certain defenses by not raising them as to the original complaint. The District Court of Nevada is the latest court to find that a defendant may assert a new Rule 12(b) defense against an amended complaint only where the defendant challenges “new matter”.

Here, Innova Electronics Corp. (“Innova”) moved to dismiss Power Probe Group’s (“Power Probe”) first amended complaint for patent infringement. Power Probe amended its complaint, adding willful infringement and infringement under doctrine of equivalents claims. In opposition, Power Probe argued because Innova did not move to dismiss the original complaint, it cannot move to dismiss a nearly identical amended one. In response, Innova argued that the original complaint was “wiped out” where its motion to dismiss was timely because it was made before a responsive pleading to the amended complaint was filed.

The Court disagreed. Noting the Ninth Circuit had not previously weighed in on this issue, the Court first looked to other in-circuit district courts[JK1] [TM2] , then two district courts outside the Ninth Circuit, that did not allow a defendant to file a 12(b)(6) motion against an amended complaint for claims asserted in the original complaint. These cases held allowing a defendant to do so weighed against judicial economy and undermined requirements of the federal rules. The Court then rejected Innova’s argument that its motion to dismiss was timely as made before any responsive pleading to the amended complaint. As the amended complaint was “almost an exact replica” of the original, Innova could have asserted a 12(b) motion against those claims but instead answered. The Court explained adopting Innova’s 12(b) interpretation to allow a motion to dismiss an amended complaint targeting original claims after the original answer “would render the 12(b) restriction on post-answer motions meaningless.” Adopting the reasoning set forth in other similar cases, the Court denied Innova’s motion to dismiss any allegation that was also present in the original complaint. That is, the Court would only consider Innova’s motion to dismiss with respect to the new allegations added to the amended complaint, which related to willful infringement and infringement under the doctrine of equivalents. The Court then denied Innova’s motion with respect to those two issues.

This case provides a reminder to carefully weigh how to respond to an original complaint, including whether to file a motion to dismiss under 12(b). Many courts will only allow a new motion to dismiss against an amended complaint to the extent it is directed at “new matter” in the amended complaint. Left unanswered by these decisions is whether these courts would allow a motion to dismiss against an amended complaint with the same claims as the original complaint, but with additional supporting allegations. Thus, while it is not unusual for a plaintiff to amend a complaint to modify its allegations, a defendant may only get one chance to dismiss allegations under 12(b). So, if a defendant does not move with respect to the original complaint, it may have waived its ability to move to dismiss those claims later.

Photo via Adobe Stock #213119758

This week, the Federal Circuit reversed the United States District Court for the District of Delaware’s (“District Court”) decision to add David Howard as a joint inventor on Hormel Food Corporation’s (“Hormel”) U.S. Patent No. 9,980,498 (“the ’498 patent”). Despite the District Court finding the opposite, the Federal Circuit found that Howard’s contributions to the ’498 patent were “insignificant in quality” under the Pannu factors.

The ’498 patent is directed to methods of cooking precooked bacon and other meat products. Specifically, the ’498 patent claimed a two-step method of cooking bacon: (1) a preheating step using a lower temperature “microwave, infrared oven, and hot air” method, and (2) a second, higher-temperature cooking step. The first step creates a layer of melted fat around the meat which protects the meat from condensation that would wash away flavor or texture in the second step. In 2007, Howard and Hormel entered into a joint agreement to develop an oven for a two-step cooking process in an effort to improve “color development” when cooking pork. During the testing, Hormel began to use, among other sources, an infrared oven as one of the heating sources for the preheating step. Howard claimed that he was the one who disclosed the infrared preheating concept. In May 2018, the ’498 patent issued, but did not list Howard as an inventor.

In April 2021, HIP, whose predecessor was Howard’s employer at the alleged time of the invention, sued Hormel, arguing that Howard was a sole or joint inventor of the ’498 patent. The District Court found that because Howard contributed the “infrared preheating” portion of the patent claims, which stood out from the remainder of the independent claims that did not include an infrared preheating element, Howard was at least a joint inventor. The Federal Circuit disagreed. Citing to the second Pannu factor, which provides “an inventor ‘must make a contribution to the claimed invention that is not insignificant in quality, when that contribution is measured against the dimension of the full invention,’” the Federal Circuit found that the invention was really about the two-step method for cooking bacon, reasoning that (1) there were any number of heat sources (like a microwave) to carry out the preheating step, and (2) the infrared oven was mentioned only once in the patent specification, indicative of its insignificance to the invention. The Federal Circuit added further fuel to the fire by emphasizing that the microwave oven was “central[]” to the claims, figures, and specification.

Parties looking to be listed as joint inventors on patents should take care to ensure that their contributions, to the extent that they are significant, are present across the specification, figures, and claims of the patent. Should inventorship disputes arise, courts will look to the evidence present in the entirety of the patent for inventorship determinations.

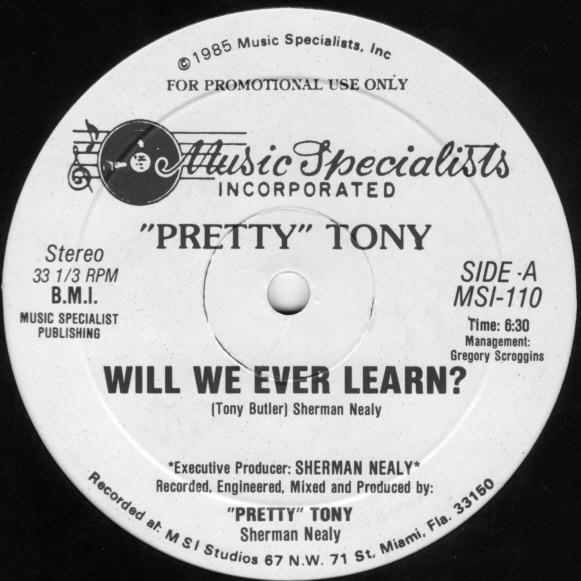

Today, much of the revenue a musician can generate from their music happens automatically through registrations with the different performing rights organizations. Unfortunately, however, there are many unscrupulous individuals who have taken advantage of their knowledge of this complicated system, and the average artist’s lack of knowledge of the system, to divert these revenues to themselves, or, more likely, a shell corporation controlled by them. This was the fate of one of Irwin IP’s pro bono clients. But, fortunately for him, Irwin IP’s Special Counsel for Entertainment and Pro Bono Services, Alexa Tipton, was there to save the day. Irwin IP is proud to announce that after Alexa’s extensive effort, Irwin IP was able to correct the record, secure our client’s rights to his music, and help him obtain thousands of dollars in back royalties.

If you are composing and releasing music, it is important to know the numerous ways in which you can automatically obtain revenue from that work. If you have any questions, please reach out to Alexa Tipton at [email protected].

Congratulations to incoming Irwin IP associate, Emad Mahou, for his remarkable work at DePaul University’s Asylum and Immigration Law Clinic.

Emad’s dedication and compassion in assisting asylum seekers in Chicago is truly inspiring. His contributions have made a significant impact helping vulnerable individuals find safety and security in the United States.

Irwin IP looks forward to welcoming Emad as an incoming associate and furthering the firm’s deep commitment to pro bono.

Read the full article here –> https://www.cbsnews.com/chicago/news/depaul-asylum-immigration-law-clinic/

In an appeal before the Federal Circuit, plaintiff People.ai argued to no avail that the Northern District of California erred in its finding of invalidity for a set of business-analytics software patents under 35 U.S.C. § 101. The plaintiff appealed, claiming that its patents did not contain patent ineligible subject matter and, if they did, included distinct, inventive concepts. Unfortunately, People.ai couldn’t automate the court’s response, and the Federal Circuit affirmed the District Court, explaining that automating a longstanding, manual process fails the Section 101 Test as set forth in Alice/Mayo.

Section 101 states that “[w]hoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.” Courts have long held that certain categories fall outside the scope of patent-eligible subject matter under Section 101, and the Supreme Court established a two-step test for determining whether claims of a patent fall outside of the scope in its decisions in Alice Corp. and Mayo Collaborative Servs. These exceptions include laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas. The two-step test, called the Alice/Mayo Test for short, asks (1) whether the claims are directed to a patent ineligible concept (one of the exceptions) and (2) whether the claims contain an inventive concept sufficient to transform the concept into a patent-eligible application. The Federal Circuit found against the patentee on both steps.

The Federal Circuit reviewed the case de novo, but agreed entirely with the District Court that the claims at issue were directed to a patent ineligible concept, namely, the abstract idea of data processing by restricting certain data from further analysis based on various sets of generic rules for each patent. The Federal Circuit agreed with the District Court’s description of the claims to be a type of filtering traditionally used in a corporate mailroom or by a salesperson who “discards the junk mail before updating the business files she maintains with relevant communications.” People.ai tried to distinguish their claims from an abstract concept, the process conducted by humans, based on (1) the specificity of the steps, (2) the removal of subjectivity, and (3) the limitations of humans. People.ai then argued that its claims were transformed into patent-eligible concepts based on (1) the ordered combination, (2) the filtering rules, and (3) the node profiles. The Federal Circuit disagreed at both steps, explaining that the claims of the patents did “not claim a different method than that traditionally used long before the application of computer technology to the problem of sorting correspondence,” and explained that “the abstract idea cannot provide the inventive concept.”

Businesses looking to patent this sort of technology must demonstrate an inventive concept; that a computer process helps do something faster or more efficiently is simply not enough.

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY

On March 24, 2023, the Southern District of New York held that the Internet Archive (“IA”)’s digitization and lending online of the Hatchette Book Group (“Publishers”)’s copyrighted physical books infringed Publishers’ copyrights and was not a fair use.

IA is a non-profit organization that allows patrons to check out eBooks through an online open library just as one would physical books at a traditional library. IA digitally scanned millions of public domain and copyrighted print books, locked the copyrighted books in containers, and made digital copies available on IA’s websites via “Controlled Digital Lending” (CDL). Under CDL, for each copy of a book IA owned, it could loan only one digital copy at a time.

On June 1, 2020, Publishers sued IA for infringing their copyrights in 127 works and challenged this lending model. The parties filed cross-motions for summary judgment (“SJ”). IA did not contest infringement but argued its use fell within the “fair use” exception. The Court disagreed, finding IA’s use not a fair use largely because it did not add something new to alter the expression or meaning of the work; it merely “space-shifted” the work from physical to digital form. As such, the Court granted Publisher’s SJ motion for copyright infringement, and denied IA’s SJ motion asserting that its use was a fair use.

The decision mainly focuses on fair use, but that is not the real reason IA’s case imploded. Fair use is a necessary but unreliable safety net for avoiding unwanted edge cases where copyright law fails to fulfill its purpose. Physical libraries rely not upon fair use (much less publisher cooperation) to protect their book-lending practices, but the ironclad protection of the “first sale” doctrine codified at 17 U.S.C. § 109. Generally, the doctrine guarantees an owner of a copy of a copyrighted work the right to dispose of that copy as they please. However, it does not enable reproduction of the work or creation of derivatives.

IA tried to apply to the digital medium the physical library model of lending the copy it owns. However, every act of using, moving, or viewing an eBook involves copying (i.e. reproduction) because of how computer devices work. Even in cases such as Capitol Recs. v. ReDigi, where ReDigi took extreme steps to make transfer of a digital good replicate a physical handoff by ensuring only one copy of the digital good existed at a time, courts still found it to constitute reproduction not protected by the first sale doctrine. Thus, IA could not simply buy an eBook and ‘lend the copy it owns.’ IA tried to circumvent this by making its own eBooks, but that, the Court found, created infringing unauthorized derivative works.

This case is another canary in the coalmine for copyright’s regressive effects on the public library model. The first sale doctrine fell behind the technological curve. The law disallows digital equivalents of actions allowed in the physical realm (e.g. handing someone a book). This is a problem: entrenched legal doctrines exist for a reason. Unshackled in the digital world, publishers can and do restrict use of works, treat libraries differently, and extract more profits from libraries and users alike at the cost of the free flow of knowledge. This will worsen as digital supplants print (even as publishers’ production costs plummet)

Photo by Gerd Altman via Pixabay

On April 4, 2023, in a case of first impression, the Federal Circuit reversed the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) and held that a trademark applicant cannot use the priority date of a prior application when the goods and services are not listed in the prior application. Bertini—a professional jazz musician who has been using the mark APPLE JAZZ in connection with festivals and concerts and distributing music since the 1990s—claimed priority of use in the APPLE mark. Apple likewise claimed priority, though, based on its 2007 purchase of the APPLE mark from The Beatles, whose use dated back to the 1960s, and based on Apple’s alleged ability to “tack” its own use of the mark back to the 1960s. The Court disagreed with Apple and reemphasized and clarified the narrow nature of the tacking doctrine.

In trademark law, tacking allows trademark owners, in limited circumstances, to “clothe a new mark with the priority position of an older mark.” In practice, this allows brands to modernize their trademarks in response to changing marketplaces without worrying they will lose all trademark rights they previously established. However, the marks must create the same commercial impression in the minds of consumers, cannot be substantially altered, and must be for substantially identical goods and services. For example, the trademark “American Security Bank” could be tacked onto the company’s prior use of “American Security” since the marks were used for the same services and a consumer would understand the two marks identify the same source.

With that background in mind, the Court noted this case raises a question of first impression: whether a trademark applicant can establish priority for every good or service in its application merely because it had priority through tacking in a subset of goods or services listed in its application. The Court held a trademark applicant could not establish priority that way. Specifically, Apple had priority of use in only “gramophone records featuring music” and “audio compact discs featuring music”—the classes of goods for which The Beatles’ APPLE mark was registered. The Court explained, however, that this partial overlap in use does not give Apple the ability to tack those earlier limited rights to a broader, new APPLE trademark application. Because Bertini had priority of use in the APPLE mark for live musical performance, Apple could not tack its APPLE MUSIC mark for live performances onto its APPLE mark for gramophone records. The Court found the appropriate standard for tacking is whether the new and old goods or services are “substantially identical” and noted that no reasonable person would find live musical performances and gramophone records substantially identical.

This case demonstrates the narrow application of tacking not only applies to the similarity of marks but also extends to the underlying mark registration classes. Before attempting to tack onto an older mark, be sure first to consider whether the marks are being used for “substantially identical” goods or services.

Several players in the replacement auto parts industry, including LKQ Corp. represented by Mark Lemley and Mark McKenna of Lex Lumina PLLC, and Barry Irwin, Iftekhar Zaim and Andrew Himebaugh of Irwin IP LLP., are urging the full Federal Circuit to reconsider the criteria used for determining the invalidity of design patents as obvious. They argue that the court’s current approach treats design patents more like trademarks than utility patents, making it extremely challenging to invalidate them.

LKQ Corp. is seeking a review of the test for obviousness in design patents, particularly in their unsuccessful attempt to invalidate General Motors’ auto design patents. They have gained support from four amicus petitions, all of which emphasize that design patents should not receive special treatment.

To read the full article, visit: https://www.law360.com/articles/1594741/full-fed-circ-urged-to-treat-design-patents-like-patents

*This article is located behind a paywall and is only available for viewing by those with a subscription to Law360.

Clever covert spy activities during active litigation may backfire. Recently, Magistrate Judge Kathleen L. DeSoto recommended dismissing all of Site 2020’s patent infringement claims against Superior Traffic with prejudice because Site 2020 acted in bad faith and “engaged deliberately in deceptive practices that undermine the integrity of judicial proceedings.”

Site 2020 and Superior Traffic are competitors in the portable traffic signal industry. In May of 2021, Site 2020 filed suit, alleging infringement of two patents related to traffic control systems. In the same month, Site 2020’s controlling entity acquired a construction company that had previously met with Superior Traffic to discuss the possibility of the two companies doing business together. Later, Superior Traffic contacted the construction company for another business pitch, not knowing of the company’s new affiliation with Site 2020. Site 2020 sent a Site 2020 manager to attend a Superior Traffic product demonstration posing as an employee of the construction company. The entire meeting, including Superior Traffic’s detailed explanation of its technology, was secretly recorded, and the recording was handed to Site 2020. After learning of the deception, Superior Traffic moved the court to (1) dismiss Site 2020’s claims with prejudice and (2) enter default judgment against Site 2020 on all of Superior Traffic’s counterclaims.

The court first noted that not only did it have the authority to sanction a party based on bad faith litigation misconduct, it also has the inherent authority to impose “case terminating sanctions” when “a party has engaged deliberately in deceptive practices that undermine the integrity of judicial proceedings” or “has willfully deceived the court and engaged in conduct utterly inconsistent with the orderly administration of justice.” The court noted five factors courts should consider when imposing case terminating sanctions: (1) the public’s interest in expeditious resolution; (2) the court’s need to manage its dockets; (3) the risk of prejudice to the party seeking sanctions; (4) the public policy favoring disposition of cases on their merits; and (5) the availability of less drastic sanctions.

In dismissing Site 2020’s claims, the court “[had] no difficulty finding by clear and convincing evidence that Site 2020 acted willfully and in bad faith.” The court found that Site 2020 circumvented the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure governing discovery and interfered with Superior Traffic’s right to be represented by counsel. Declaring that “[t]he prejudice Superior Traffic has suffered because of Site 2020’s misconduct cannot be minimized,” the court found that although the public policy factor weighs against dismissal, the factor is heavily outweighed by the other four and that Site 2020’s misconduct undermined the integrity of the litigation process, as well as Superior Traffic’s confidence in the federal judicial system. While Site 2020’s claims were dismissed, the court declined to enter judgment on Superior Traffic’s counterclaims, finding that too severe a sanction under the circumstances. This case serves as a powerful reminder that “case terminating sanctions” are still very much alive—for the spies.

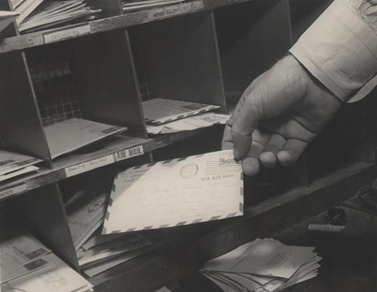

The Eleventh Circuit joins the Ninth Circuit where, despite a claim of copyright infringement having a three-year statute of limitation, a plaintiff can recover damages more than three years prior to the suit. Recently, the Eleventh Circuit weighed in on the current circuit split finding neither the Supreme Court’s decision in Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 572 U.S. 663 (2014), nor the Copyright Act’s statute of limitations, bars recovery for damages for infringement which occurred more than three years prior to the suit if the copyright owner discovered the infringement within those three.

Plaintiffs alleged that due to invalid licenses obtained from third parties defendants are infringing copyrights in certain musical works. The infringement allegedly began in 2008, but plaintiff was in-and-out of prison and uninvolved in the music industry until 2016 when he discovered the infringement. Plaintiff filed suit for copyright infringement in 2018 seeking damages as far back as 2008. Defendants argued that damages should be “limited to the three-year lookback period as calculated from the date of the filing of the Complaint pursuant to the Copyright Act and Petrella.”

Petrella held that the doctrine of laches does not bar copyright claims within the three-year statute of limitations period and that the statute “bars relief of any kind for conduct occurring prior to the three-year limitations period.” The Second Circuit agrees, strictly interpreting Petrella as barring any recovery outside of the three-year lookback. The Ninth Circuit disagrees, holding that Petrella does not limit recovery if the filing of suit was timely.

The Eleventh Circuit has joined the Ninth Circuit, noting that Petrella based its ruling on a claim that was brought under the injury rule. Under the injury rule, a claim for copyright infringement accrues and the statute of limitations begins to run once an act of infringement occurs, no matter when the plaintiff learns of it. Conversely, the Eleventh and Ninth Circuits apply the discovery rule in which the statute of limitations runs once the plaintiff learns, or reasonably should have learned, the defendant has violated his rights.

Thus, the Eleventh Circuit concluded Petrella did not cap damages for claims that were timely filed under the discovery rule, because Petrella did not address the discovery rule. In addition, the Eleventh Circuit concluded that the plain text of the Copyright Act only bars the ability for plaintiff to recover if he does not bring a timely action, and that it does not dictate the remedy a plaintiff may obtain if a timely action is brought. Hence, a damages claim that satisfies the statute of limitations based on the discovery rule is not limited to three years. Therefore, copyright holders seeking to enforce their rights should determine where personal jurisdiction is available in either the Ninth or Eleventh Circuits to potentially allow recovery of damages beyond three years.