Courts continue to measure that fine line between reliable expert testimony and legal opinion that patent experts constantly walk on. In a recent opinion, the Eastern District of Texas denied a patentee’s motion to exclude the accused infringer’s expert testimony holding that the expert was merely doing his job, rather than trying to offer legal opinions.

SB IP Holdings LLC (“SBIP”) sued Vivint, Inc. (“Vivint”) for patent infringement. Vivint asserted inequitable conduct as a defense, alleging that SBIP made false statements to the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“PTO”) during the prosecution of a relevant patent application. Specifically, Vivint alleged that SBIP falsely represented to the PTO that an earlier application was still pending at the same time as one of the applications that led to the patents-in-suit in order to improperly obtain priority, even though SBIP knew that the earlier application had been abandoned for months and could not support a claim for priority. Relying on SBIP’s alleged misrepresentation, the PTO issued the asserted patents. To support its defense, Vivint retained Mr. Robert Stoll, a former Commissioner for Patents at the USPTO, to provide expert testimony regarding PTO practices and procedures and their application in this case. While not challenging Mr. Stoll’s qualifications, SBIP moved to exclude Mr. Stoll’s testimony, arguing that: (1) Mr. Stoll offered legal opinions and conclusions that invaded the province of the court; (2) Mr. Stoll improperly “narrated” evidence; and (3) Mr. Stoll’s testimony regarding the impact of the allegedly false statements on the PTO and the intent of the various speakers was impermissible speculation.

The court denied SBIP’s motion. As an initial matter, the court observed that the court’s gatekeeping role for expert testimony is less important when, as was the case here, the expert testimony in question would be presented in a bench trial. Then, in denying SBIP’s motion, the court made several findings. First, the court recognized that “there is a fine line” between an expert opinion that properly applies a legal framework to the facts and one that impermissibly provides legal opinions, and that the line is particularly difficult to draw in patent cases. However, the court found that Mr. Stoll did not “stray so far over the line” because (1) his citations to legal authorities are only intended to explain his analysis rather than to usurp the court’s role as the arbiter of the law, and (2) his testimony was based on his extensive familiarity with USPTO practice and procedure. Second, the court ruled that it would not strike the portions of Mr. Stoll’s reports that set out background facts because it is entirely permissible for an expert to explain the facts that form the basis of his opinion. Finally, the court found that Mr. Stoll’s testimony related to materiality was sufficiently reliable and SBIP’s arguments regarding speculation were better addressed through “cross-examination and presentation of contrary evidence” as the issue went to weight rather than admissibility. This case demonstrates that when expert testimony will be presented in a bench trial, the judge is likely to give more leeway in expert reports when there are no jury concerns.

On June 2, 2023, the Ninth Circuit reversed a dismissal of Plaintiff Enigma Software Group’s (“Enigma”) Lanham Act false advertising and related state law claims against its competitor, Defendant Malwarebytes, Inc. (“Malwarebytes”). The primary basis for the reversal was that designating Enigma’s products as “malicious,” “threats,” and “malware” were, per the Court, actionable statements of objective fact, subject to being found false, and not merely subjective opinions protected by the First Amendment.

Both Enigma and Malwarebytes operate in the anti-malware and computer security market. Among other things, their products help consumers detect and remove malicious software. In October 2016, Malwarebytes began identifying Enigma’s products as “malware,” “malicious,” “threats,” or a “potentially unwanted program.”

Malwarebytes won various procedural triumphs in the District Court in California over the last several years, getting the claims dismissed the first time around because the Court found all of Enigma’s claims were barred by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, 47 U.S.C. § 230(c)(2), and the second time around because the Court found the statements were nonactionable opinions. However, the Ninth Circuit reversed and remanded on both instances, this time finding that Malwarebytes’s statements were actionable statements of objective fact that could be false or misleading.

While there are five elements to state a claim for false advertising under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, the District Court only addressed part of the first element: whether there was a false statement of fact as opposed to an opinion or subjective suggestion. The District Court found Malwarebytes’s designations of Enigma products as “malware,” “malicious,” “threats,” and “potentially unwanted program” to be subjective opinions, but the Ninth Circuit reversed, in part, finding the first three designations made a claim as to a specific characteristic of a product and were thus actionable statements of fact under the Lanham Act, noting whether or not these claims are true would be tested on the merits. The Court also noted that on remand, the District Court would need to consider in the first instance whether the statements were “commercial speech,” and whether they deceived a substantial segment of the relevant audience, alternate bases on which Malwarebytes requested dismissal.

Judge Bumatay, in his dissent, disagreed, noting that flagging a competitor’s products as “threats” or “malicious” are subjective statements and not readily verifiable. Specifically, he cautioned: “By treating these terms as actionable statements of fact under the Lanham Act, our court sends a chilling message to cybersecurity companies—civil liability may now attach if a court later disagrees with your classification of a program as “malware.”

On June 8, 2023, the Supreme Court vacated a Ninth Circuit decision holding that a poop-themed chewable dog toy resembling a Jack Daniel’s whiskey bottle was protected by the First Amendment and did not infringe Jack Daniel’s trademark rights. This case makes the use of the parody exception defense—which a number of courts have relied on when applying the Rogers test and finding the parody to be protected speech—more challenging.

Jack Daniel’s Properties (“Jack Daniel’s”), a whiskey company, owns trademarks in the bottle, words, and graphics used on Jack Daniel’s bottle, including JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7. VIP Products (“VIP”), a dog toy company, began selling squeaky, chewable dog toys designed to look similar to Jack Daniel’s whiskey bottle but with slightly different wording: VIP replaced “Jack Daniel’s” with “Bad Spaniels” and “Old No. 7 Brand Tennessee Sour Mash Whiskey” with the “The Old No. 2 On Your Tennessee Carpet.”

After VIP began selling its chew toys, Jack Daniel’s sent a cease-and-desist letter to VIP. In response, VIP filed a declaratory judgment that the Bad Spaniels chew toy did not infringe nor dilute Jack Daniel’s trademarks. VIP moved for summary judgment, asserting (1) that the Second Circuit’s Rogers test (which has permitted dismissal of a trademark infringement claim for “expressive works”) applied to VIP’s parodic use of the Jack Daniel’s product and (2) that the dilution claim could not succeed because Bad Spaniels was a “parody” of Jack Daniel’s and, therefore, made “fair use” of its famous marks. However, the district court rejected VIP’s arguments, finding the cribbed bottle features to be essentially using Jack Daniel’s trademarks for source identification and, thus, the Rogers test did not apply. After a bench trial, the district court found the products likely to be confused based on survey evidence and to cause reputational harm by creating “negative associations” with “canine excrement.” The Ninth Circuit reversed, finding the Bad Spaniels product to be an expressive work subject to the Rogers test because it parodies Jack Daniel’s. The Ninth Circuit also found the exclusion for “noncommercial use” shielded VIP from liability and that the “use of a mark may be ‘noncommercial . . . even if used to sell a product.”

The Supreme Court, agreeing with the district court, held that the Rogers test does not apply when a trademark infringer uses a trademark as a designation of source for the infringer’s own goods, as VIP did here. VIP’s use of the Jack Daniel’s trademarks was more trademark use than parody for three reasons: (1) Bad Spaniels alleged that they had trademark rights in “Bad Spaniels,” (2) Bad Spaniels used the Bad Spaniels mark in the top right of the product next to their other mark, Silly Squeakers, and (3) they had a line of similar products and had obtained trademark registrations on those products. The Court further held the noncommercial exclusion does not shield parody when use is source-identifying. The court noted, however, that parody and free expression considerations may still come into play in likelihood-of-confusion analyses. This case limits the applicability of the Rogers test to expressive works where marks are not used as source identifier and increases the risk associated with creating certain parody works that use or rely on trademarks for the intended commentary. Should a business have a work that parodies another’s trademark rights, that business should be careful to avoid using the parody products to signify their own brand and avoid asserting rights in the parody work (i.e., obtaining trademark protection).

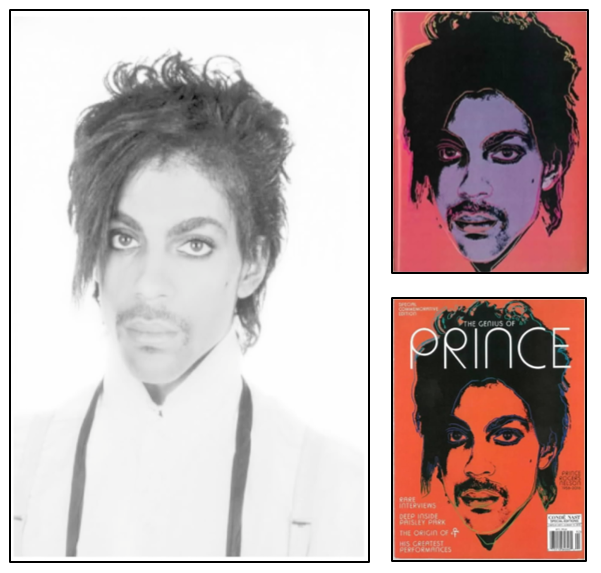

In a highly anticipated ruling, the Supreme Court found that the Andy Warhol Foundation (“AWF”)’s licensing of “Orange Prince” to Condé Nast was not “fair use” of a Lynn Goldsmith photograph that served as the basis for Andy Warhol’s Prince Series. In affirming the Second Circuits’ ruling that the “purpose and character” of AWF’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph did not militate fair use, the Supreme Court clarified that “transformativeness” under the first fair use factor focuses on changes to the purpose of the work (and not just its aesthetics or subjective interpretation), and that transformativeness cannot displace analysis of other relevant factors.

Goldsmith, a leading professional photographer of rock and roll musicians, took a series of portrait photos of Prince in 1981. In 1984, Vanity Fair licensed one such photo on a one-time basis for use as an “artist reference” in a story about the musician. The magazine then hired Warhol who created a silkscreened image using the photo. When Vanity Fair published the resulting work, “Purple Prince,” it credited Goldsmith for the “source photograph.”

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol also used Goldsmith’s photo to create fifteen more works, collectively known as the “Prince Series.” After Prince’s death in 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent company, Condé Nast, sought to publish a special edition magazine commemorating Prince. Initially, Condé Nast contacted AWF to reuse “Purple Prince,” but upon learning of the Prince Series, instead elected to license “Orange Prince” for $10,000. This time, Goldsmith was neither credited, nor compensated. Goldsmith informed AWF that she believed the use of her photo infringed her copyright. AWF then sued Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment that AWF did not infringe or, in the alternative, that Warhol’s use constituted “fair use.”

The fair use doctrine is an affirmative defense against copyright infringement and reflects congress’s intent to balance the promotion of creativity with the protection against undue restrictions on copying in order “to promote the progress of science and the arts without diminishing the incentive to create.” The Copyright Act enumerates four factors for courts to consider in determining whether a use is “fair.”[1] The first factor, the only one addressed by the Supreme Court’s opinion, asks, “whether the new work ‘merely supersedes the objects’ of the original creation (supplanting the original), or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character.”

The District Court granted AWF summary judgment of fair use seemingly based on the aesthetic and artistic merit of Warhol’s work. The District Court found Warhol’s Prince Series was “transformative” because it “transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic larger-than-life figure” such that “each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than a photograph of Prince.” The District Court then relied on that finding to discount the importance of the other fair use factors “because the Prince Series works are transformative,” “Warhol removed nearly all the photograph’s protectable elements,” and that the Prince Series were not market substitutes for Goldsmith’s works. On appeal, the Second Circuit reversed, holding that the two works are substantially similar and that all four fair use factors in fact favor Goldsmith.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari on only the narrow question of “whether the first fair use factor … weighs in favor of AWF’s recent commercial licensing to Condé Nast.” Much of the dissonance between the majority opinion and the dissent stems from the Justices’ widely diverging interpretations of what the first fair use factor is asking courts to examine. More specifically, the Court focused on the meaning and significance of whether a use of a copyrighted work was “transformative” of the original. The dissent subscribed to AWF and the District Court’s understanding that the first factor concerns the extent to which Warhol’s work (i.e. the Prince Series) “transformed” the aesthetic and artistic meaning of Goldsmith’s photograph, whereas all seven other Justices emphasized that it is how the work is used that matters for fair use, and not its artistic significance or the artist’s subjective intent.

The term “transformative” entered the vernacular of copyright jurisprudence via a 1990 Harvard Law review article authored by Judge Pierre N. Leval, then a District Court Judge at the Southern District of New York.[2] In that article, Judge Leval argued that the essence of the “character and purpose” portion of the first fair use factor was that the use “must employ the quoted matter in a different manner or for a different purpose from the original.” Id. This philosophy was then adopted by SDNY in 1991[3], the Second Circuit in 1993[4], and the Supreme Court in 1994.[5] However, unlike the AWF District Court’s interpretation, these early cases all focused on how the accused work was being used (e.g. whether they commented on or criticized the copyrighted work) and not their artistic merit.

So how, then, did courts detour into the business of art critique? The majority identified the culprit to be a paraphrase in Campbell of Judge Leval’s article stating that a transformative use is one that “alter[s] the first [work] with new expression, meaning, or message.” It is true that the “meaning of a secondary work, as reasonably can be perceived, should be considered to the extent necessary to determine whether the purpose of the use is distinct from the original[.]” However, “Campbell cannot be read to mean that § 107(1) weighs in favor of any use that adds some new expression, meaning, or message” because that would obliterate the copyright owner’s right to prepare derivative works. To make “transformative use” within the meaning of the first fair use factor, “the degree of transformation … must go beyond that required to qualify as a derivative.” Here, the purpose for which Orange Prince was licensed to Condé Nast and the purpose for which Goldsmith licensed the original Prince photograph are similar: provision of a visual depiction of Prince to accompany a magazine article on Prince.

The Supreme Court emphasized the importance of considering and balancing all parts of the first fair use factor. The first factor considers the degree to which the “purpose and character” of the accused use is different from (i.e. “transformative” of) that of the use of the original work. “The larger the difference, the more likely the first factor weighs in favor of fair use.” But transformativeness alone is not dispositive. The court should also consider whether the use is commercial or non-profit, but again, that alone is not dispositive; it must be weighed against the degree to which the use is transformative. If the “original work and the secondary work share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is of a commercial nature, the first factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying.” One possible justification for a use might be if copying is reasonably necessary to achieve the user’s new purpose. The AWF District Court erred by interpreting transformation so broadly that it swallowed up a copyright owner’s exclusive right to create derivative works, and then elevated transformativeness above all other aspects of the first factor (commercial use and justification) and other fair use factors.

[1] The four “fair use” factors in § 107 include “(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.”

[2] Leval, Toward a Fair Use Standard, 103 Harv. L. Rev. 1105, 1111 (1990).

[3] Basic Books, Inc. v. Kinko’s Graphics Corp., 758 F.Supp. 1522, 1530 (S.D.N.Y. 1991) (copying excerpts of books for compilation into university course packets was not a fair use).

[4] Twin Peaks Productions, Inc. v. Publications Int’l, Ltd., 996 F.2d 1366, 1375‑76 (2d Cir. 1993) (book disclosing detailed plot summaries of a television program without any critical commentary served no transformative purpose and was not a fair use).

[5] Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 578-580 (1994) (holding that the Second Circuit erred by cutting its inquiry into the first factor off upon finding the allegedly infringing use was of a commercial nature and explaining that a parody of a song could be fair use as “parody has an obvious claim to transformative value,” e.g., by “shedding light on an earlier work”).

In a stark order, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) invalidated patents because a patent owner failed to disclose test results that were inconsistent with the patent owner’s arguments, underscoring the PTAB’s focus on holding parties accountable when they fail to meet their duty of candor and fair dealing before the Board. This case can be contrasted with district court litigation, where it has become increasingly difficult to invalidate a patent for failure to disclose information, due to the focus on intent to deceive. This dispute involved five inter partes reviews (IPRs) in which Spectrum Solutions LLC challenged five patents held by Longhorn Vaccines & Diagnostics, LLC. In the IPR proceeding, Longhorn attempted to bolster one of its arguments by relying on biological testing from Assured BioLabs, LLC (ABL) to distinguish an asserted reference. During the depositions of ABL employees, a dispute over an attorney work product objection arose. Attorneys for Longhorn had told the ABL witnesses not to answer questions that were material to the case, and the witnesses indicated that there may be withheld testing information related to the patentability of the claims. As a result, the PTAB authorized briefing on the issue and ordered Longhorn to serve relevant information as required by IPR rules. Longhorn made three ABL witnesses available for further cross examination, and served Spectrum with additional documents relating to its testing. Spectrum sought sanctions, including an entry of judgment against Longhorn.

The PTAB noted parties “have a duty of candor and good faith to the Office during the course of a proceeding[.]” Parties are obliged to disclose information that is “material to patentability when it is not cumulative to information already of record or being made of record” and if “[i]t refutes, or is inconsistent with, a position the applicant takes in . . . assessing patentability[.]” The rules require “service of relevant information that is inconsistent with a position advanced by the party during the proceeding concurrent with the filing of the documents . . . that contains the inconsistency.” Notably, Longhorn had selectively withheld test results that were inconsistent with its arguments. Citing governing rules, the PTAB stated that it has discretion to impose a sanction against a party for misconduct, including “[f]ailure to comply with an applicable rule or order in the proceeding,” “[m]isrepresentation of a fact.” Longhorn’s arguments that the withheld information was protected by attorney-client privilege or attorney-work product did not hold up. The PTAB stated, “[t]hese doctrines cannot be used to shield factual information from discovery that is inconsistent with positions taken by a party before the board.” The PTAB found that Longhorn had “acted deliberately in failing to comply with its duty of candor and good faith before the Board, that [its] behavior was egregious, and that protecting the PTO’s interests, and those of the public, properly includes judgment against [it].” As a sanction, the PTAB cancelled all claims of the challenged patents.

A key takeaway from this order is that a party in an IPR proceeding should carefully consider whether conducting scientific testing to strengthen an argument is worth it, given that testing results must be turned over regardless of outcome. Most importantly, this case serves as a powerful reminder that the duty to disclose is alive and well, and selective non-disclosure of material information can abruptly end a case before the PTAB.

Irwin IP is incredibly proud to celebrate Emad’s remarkable journey from being a Syrian refugee to graduating from DePaul University. Emad’s story is one of resilience, determination, and triumph over adversity.

As Emad joins our team, we eagerly anticipate the positive impact he will bring with his unique perspective, skills, and dedication. His success is a testament to the power of education and the limitless potential within each of us.

Emad, we warmly welcome you aboard and look forward to witnessing your remarkable contributions!

The Chicago Tribune has published a detailed account of Emad’s remarkable journey. Read the full article here–>

Picture via John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune

In a legal dispute linked to the film “Gone in 60 Seconds,” an attorney representing the movie’s producer presented their argument centered on Carroll Shelby’s company allegedly violating a settlement concerning the rights to the movie’s iconic “Eleanor” car by taking legal action against actions they were authorized to perform.

The core issue revolves around a disagreement over reproducing Eleanor Mustangs. Denice Halicki, widow of the original film’s director and a producer of the remake, defended her stance, asserting that her cease-and-desist letters to those reproducing Eleanors were well within her rights.

David L. Brandon, from Clark Hill PLC, emphasized that the Shelby parties had initiated legal action despite the settlement explicitly prohibiting them from suing Halicki for various actions related to Eleanors from the remake. This legal clash originates from a 2009 settlement following a previous lawsuit between Halicki and Shelby’s company and trust. Classic Recreations LLC, known for crafting custom Mustangs for Shelby, is also entangled in the lawsuit.

The initial dispute traces its roots to the 1974 film “Gone in 60 Seconds,” featuring a Ford Mustang named “Eleanor.” The 2000 remake continued to use the name Eleanor, leading to disputes over the car’s true identity. Shelby’s trust attempted to trademark “Eleanor” for both model and real cars, triggering legal proceedings initiated by Halicki.

Both parties sought summary judgment, with Judge Scarsi dismissing Halicki’s copyright claims. During the recent hearing, Halicki’s attorney, Jason J. Keener of Irwin IP LLC, presented evidence supporting the assertion that the GT500CR mimicked Eleanor, while the representation of Classic Recreations argued that Halicki’s claims were time-barred.

A ruling on the contract’s interpretation could significantly influence future car sales. Halicki is pursuing potential damages of up to $16.8 million and injunctive relief, while the Shelby parties are seeking over $429,000 in damages and an interpretation of the 2009 agreement that would allow them to continue selling their cars. Judge Scarsi has not yet issued a ruling.

To read the full article, visit: https://www.law360.com/articles/1685036/-60-seconds-producer-says-shelby-s-co-s-suit-crashed-deal?copied=1

*This article is located behind a paywall and is only available for viewing by those with a subscription to Law360.

Irwin IP is thrilled to announce and extend a heartfelt welcome to the 2023 summer associates. It’s an exciting time as they join us with impressive credentials and a passion for intellectual property law.

Throughout the summer, our associates will collaborate with experienced attorneys, engage in real-world projects, and gain valuable hands-on experience. We’re committed to fostering their growth and providing a supportive environment for their professional development.

We look forward to witnessing their contributions and achievements during their time at Irwin IP. Let’s make this summer an unforgettable one!

Few litigation events cause tempers to flare as surely as depositions, but only once in a blue moon, it seems, will a Court take action against an attorney for violating the rules. However, the planets aligned over the District of Colorado on May 5 when counsel for a defendant in a lawsuit brought by motivational speaker, influencer, YouTube personality, and clone of a space-faring military operative, James Corey Goode crossed the event horizon of unprofessional conduct to discover what lies beyond: sanctions.

In 2020, Goode filed suit against three former business partners. Goode alleged the defendants infringed his Sphere Being Alliance® trademarks, which Goode used in recounting his personal close encounters of the fifth kind in various media such as the show “Cosmic Disclosure” on the Gaia Network. Among these marks are his “Blue Avian™” and “20 and Back™” marks. The “Blue Avian™” mark covers Goode’s name for angelic alien beings (aptly enough, bird-like and blue) with whom Goode claims to have contact. The “20 and Back™” mark references military operations Goode undertook for the Secret Space Program in a past life (of which Goode has total recall even though his memories of his past starship trooper adventures were supposed to have been wiped).

This story begins with a near-miss. When Goode was deposed, his attorney verbally designated all of his deposition as confidential. Defendants’ attorneys objected to the blanket designation and later challenged it again in an email, demanding Goode’s attorneys’ designate which parts were confidential. The message was lost in the currents of space and time until a month later when Goode learned that certain Vimeo and YouTube users, “Cosmic Justice” and “Truthseekers,” had uploaded videos of his deposition. Goode demanded sanctions, asserting the disclosure violated the protective order because it was the defendants’ burden to challenge the designation by motion. The Court, however, found that reading cosmically incorrect. Even though it indicated that the release of the footage “smack[ed] of unprofessionalism,” the Court found it not violative of the protective order because Goode, who had the burden to file a motion to maintain confidentiality, failed to timely respond to Defendants’ challenge of the designation.

Defendant Youngblood’s deposition, however, charted a darker course. Goode claimed that less-than-stellar conduct by Youngblood’s counsel had knocked the deposition off-axis for two hours. The provided transcript excerpts betray an extended coaching session, on the record, regarding the difference between an “estimate” and a “guess,” an instruction to Youngblood not to disclose her birthday, and objections against questions regarding finances. While the Court found the excerpted conduct “clearly sanctionable,” it could not grant the relief Goode requested due to a vacuum of evidence. Thus, the Court ordered Goode to produce the full transcript, identify the other instances of attorney misconduct, and identify and explain the type and amount of sanctions appropriately being sought.

Given Goode’s unearthly background one might be forgiven for presuming it would be Goode whom the Court would need to drag back to earth. However, things are not always as they seem, as it was Defendant Youngblood’s counsel who came into the deposition far too hot and burned up on reentry. In discovery disputes, imposition of sanctions is something of an anomaly, but, as this case proves, they do exist!

Irwin IP is pleased to welcome our newest associate attorney, Andrew Gordon-Seifert. With his impressive background in intellectual property litigation, Andrew brings a wealth of experience and a proven track record of success.

Throughout his career, Andrew has counseled and represented clients across various industries, ranging from automotive manufacturers to healthcare and home furnishings, in complex intellectual property disputes. Notably, one of Andrew’s remarkable victories was in a chemical patent case, where he helped to secure a jury verdict of over $700,000 in the Northern District of Ohio.

Andrew’s dedication, expertise, and commitment to client success makes him an invaluable addition to Irwin IP. We are excited to have him on board as we continue to provide exceptional legal services to our clients.

Pictured: Andrew Gordon-Seifert