Did the University of Illinois Fumble its Chief Illiniwek Trademark? The Northern District of Illinois Says Further Review Is Needed. Published by The Licensing Journal.

As an initial disclaimer, Irwin IP LLP is privileged to be lead counsel for LKQ Corporation and Keystone Automotive Industries, Inc. (collectively, “LKQ”) in several design patent infringement matters, including this case against GM Global Technology Operations and by extension General Motors Co. (collectively, “GM”). However, LKQ neither requested nor paid for preparation of this article, and the views expressed herein are those of the authors alone. Last year, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”), agreed to rehear en banc LKQ’s appeal of the Inter Partes review decision by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) which held that U.S. Design Patent No. D797,625 (“the ’625 Patent”) was not unpatentable as obvious. This marked the first time that the CAFC granted such a petition in a patent case in over five years—or 15 years for a design patent case.

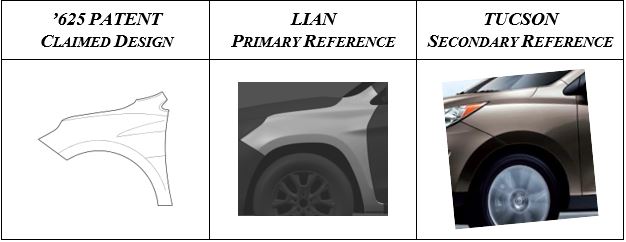

The current design patent obviousness analysis, the Rosen–Durling test (named for In re Rosen and Durling v. Spectrum Furniture), is the crux of the dispute. Rosen–Durling restricts the obviousness analysis for design patents unless a patent challenger can show that there is a single primary reference that is basically the same as the patented design and any secondary references used in combination with that “Rosen reference” must be “so related in appearance” so as to suggest their combination. LKQ argues that both prongs of this test constitute rigid rules that prevent courts and the patent office from considering what a designer of ordinary skill in the art (“DOSA”) would have found obvious. Rosen–Durling would therefore be inconsistent with the United States Supreme Court’s decisions in KSR v. Teleflex and Smith v. Whitman Saddle, 35 U.S.C. §103 (which governs the obviousness requirement for all patents), and the Intellectual Property Clause of the United States Constitution.

Ten of the active judges sitting on the CAFC, Chief Judge Moore, and Judges Stark, Hughes, Taranto, Prost, Lourie, Dyk, Reyna, Chen, and Stoll, heard oral argument from LKQ, GM, and the United States Government on Monday, February 5, 2024. Generally, GM advocated for the opposite of LKQ’s position, and the Government argued in favor of relaxing the Rosen step and abandoning the Durling step. The Judges’ questions and comments at oral argument seem to indicate that a change to design patent obviousness law may be on the horizon.

The PTAB found LKQ’s primary reference (“Lian”) failed to satisfy Rosen’s gating requirement that it be “basically the same” as the claimed design. Several judges suggested that, if so, the threshold was too demanding. Chief Judge Moore, for example, remarked “I look at both of these and they certainly give me the same visual impression….” And later: “I look at these things—no difference.” Judge Chen similarly noted: “they do look sort of the same, right? Lian and the claimed design?” And, following up on Judge Prost questioning the credibility of one of GM’s arguments, Judge Stark queried “how could either of those saddle references [in Whitman Saddle] be a Rosen Reference if the Lian reference here is not?” He continued: “if somebody tried to count the differences between the two references in Whitman Saddle and the claimed design, you would easily get to more than seven, starting with the fact that it’s a front-half, back-half situation…. I’m not sure how this is a credible argument.”

Doctrinally, the judges had even more to say about Rosen–Durling. Judge Chen questioned “the source of the legal authority the Rosen court had to articulate the basically the same command for a primary reference?” He commented: “there was no case before Rosen that mandated that requirement or articulated any version of that, certainly not the Supreme Court, and we know it’s not in the statute.” Then, Judge Dyk asked “…isn’t it true that neither Rosen nor Durling discussed Whitman Saddle?” When GM confirmed they did not, Judge Dyk noted that was “a problem.”

Indeed, some judges questioned how different the current obviousness test is from anticipation. Chief Judge Moore expressed concern with GM’s argument that a more sophisticated designer is less likely to find something basically the same: “you told me that, for example, in this art … it’s a sophisticated art with a lot of prior art, so designers are very attuned to the nuances and the differences. So that means you can get a patent on something an ordinary observer would have absolutely said is the same thing. … But that means you get infringement damages against people when the very same thing or very similar things may have been in the prior art and the ordinary designer, much more sophisticated, would have allowed you to get your patent. What do we do about that?”

It was clear by the judges’ questions regarding the analogous art doctrine, that they will consider this in any potential change. Chief Judge Moore explained that in the utility patent context, the analogous art doctrine guides against the risk of hindsight infecting the obviousness analysis and posed several questions as to how the analogous art doctrine would work in the design patent context. Later, Judge Hughes gave an instructive hypothetical: “Say you have… furniture designers, …and they routinely look to what’s happening in contemporary architecture to import designs from architecture to furniture. Wouldn’t that be something you could look to even though a design for a building is certainly not remotely in the same endeavor as a furniture designer?” Chief Judge Moore endorsed this as “absolutely correct.” Interestingly, Chief Judge Moore and Judge Stoll, who asked the most questions about analogous art, previously decided Airbus v. Firepass which held that analogous art is a fact question that hinges on record evidence of “the knowledge and perspective of an ordinarily skilled artisan.” 941 F.3d 1374, 1383-84.

The CAFC asked several questions of LKQ and the Government on how the USPTO could apply a new design patent obviousness test. Judge Prost summed up the issue: “the PTO take[s] issue with your willingness or advocacy for abrogating the threshold test by saying that … in litigation you get the benefit of design experts, but the examiners don’t have that…” But Solicitor Rasheed also stated “we think that our examiners are capable, as they are in the utility side, and as they already do on the design side, to look at the prior art and to figure out … who the person of skill in the art is and to proceed from there.”

One final note, Judge Chen asked if it were “true that only about one to two percent of all design patent applications get a prior art rejection during examination?” The Government indicated that their rate is “a little higher” and clarified “about 4%” after questioning by Judge Stoll. This statistic, which is vastly different for utility patents, is said by Professor Sarah Burstein to demonstrate that CAFC precedent makes it nearly impossible for the Patent Office to reject design patent claims (and by Professor Dennis Crouch as evidence that the Patent Office has abdicated its role in examination). See Sarah Burstein, Is Design Patent Obviousness Too Lax?, 33 BERKELEY TECH. L. J. at 608-610, 624 (2018); Dennis Crouch, A Trademark Justification for Design Patent Rights, 24 HARV. J. L. TECH. at 18-19 (2010).

It remains to be seen what change in the law the CAFC will make and to what degree, but now more than ever, LKQ v. GM is a case worth following. Stay tuned for additional entries in this series that will explore other areas of interest in this case.

Curious about A.I. and legalities in image & copy creation? Alexa Tipton and Victoria Hanson will guide you through crucial legal issues. Learn about A.I. usage with copyrighted works, “fair use,” recent Copyright Review Board decisions, trademark infringement litigation, advertising, deepfakes, and best practices for prompts.

During the Federal Circuit’s first patent case since 2018, judges hesitated to discard long-standing tests for proving design patent invalidity, with some showing openness to adjusting a standard criticized as overly rigid. LKQ Corp., represented by Irwin IP LLP and Lex Lumina PLLC, sought to invalidate two General Motors design patents, arguing that the current tests, in use for over 40 years, are excessively stringent and outdated.

Read the full article at: Fed. Circ. Questions Call To Throw Out Design Patent Tests

*This article is located behind a paywall and is only available for viewing by those with a subscription to Law360.

Federal Circuit judges expressed skepticism over the Rosen-Durling test, which has been utilized for four decades to assess the obviousness of design patents, particularly in a case involving General Motors Co. and LKQ Corp. LKQ Corp., represented by Irwin IP LLP and Lex Lumina PLLC, challenged the test, arguing it sets an unreasonably high bar and allows automakers to patent minor design tweaks, leading to inflated part prices. During a rare en banc session for the first time in 15 years, judges questioned why a previous patent referenced by LKQ Corp. did not meet the test’s criteria, suggesting a potential need for revision to ensure fairness and promote innovation in design.

To read the full article, visit: https://news.bloomberglaw.com/ip-law/gm-lkq-trade-punches-at-fed-circuit-over-design-patent-test

Irwin IP is pleased to announce that five of our attorneys have been named as 2024 Illinois Super Lawyers by Thomson Reuters. This prestigious recognition highlights their dedication to excellence and their significant contributions to the field of intellectual property law.

Among those recognized as Super Lawyers are Robyn Bowland, Barry F. Irwin, Joseph Marinelli, and Joseph Saltiel. This marks Barry’s 20th year as a Super Lawyer, where he joins a distinguished group of attorneys who have been consistently recognized since the very beginning. Additionally, we are proud to announce that Nick Wheeler has been recognized as a Rising Star, a recognition that only 2.5 percent of lawyers in the state of Illinois are named.

Congratulations to our exceptional team for this well-deserved acknowledgment!

On January 26, 2024, the Federal Circuit denied a petition for writ of mandamus to vacate an order permitting Rotolight Limited (“Rotolight”) to serve Aputure Imaging Industries Co., Ltd. (“Aputure”) through email to Aputure’s in-house counsel.

Rotolight and Aputure manufacture and sell LED lights used in photography and filmmaking. In June 2023, Rotolight filed a complaint in the Eastern District of Texas against Aputure, a China-based company, for patent infringement. Rotolight made several unsuccessful attempts to serve Aputure at a California address obtained from multiple online business databases that had the same zip code as an office listed on Aputure’s website. In September 2023, Rotolight moved for substitute service pursuant to Texas Rule of Civil Procedure 106(b) to seek permission to serve Aputure by emailing Aputure’s legal counsel.

On October 16, 2023, the Eastern District of Texas granted Rotolight’s motion for substitute service to serve Aputure via email. The court found that Rotolight had attempted service enough times on Aputure at locations reported to be its place of residence in California and that service of the complaint and summons on Aputure’s in-house counsel’s email address would be effective to give notice to Aputure of the suit. In response, Aputure filed a petition for writ of mandamus to the Federal Circuit to vacate the order and deny the request for substituted service because service by email was improper and service should have been attempted through the Hague Convention since Aputure is based in China.

The Federal Circuit denied Aputure’s petition because Aputure failed to satisfy the three conditions in order to grant a writ of mandamus: (1) the petitioner must have “no other adequate means to attain the relief [it] desires,” (2) that the “right to issuance of the writ is clear and indisputable,” and (3) the court “in the exercise of its discretion, must be satisfied that the writ is appropriate under the circumstances.” For the first factor, Aputure did not show that a post-judgment appeal would be inadequate. For the second factor, Aputure did not demonstrate that it had a clear and indisputable right to relief. Although Aputure argued that the district court erred by refusing to require Rotolight to first attempt service of process in China pursuant to the Hague Convention, that argument failed because the district court appeared to have concluded Aputure could be served in California. Further, the Federal Circuit held district courts are given broad discretion to determine alternative means of service not prohibited by international agreement. For the third factor, the Federal Circuit ultimately determined that it was not prepared to determine that granting the motion was a clear abuse of discretion that warranted mandamus relief.

While a denial of the writ of mandamus does not determine whether the district court’s grant of the motion for substitute service was an abuse of discretion, this case demonstrates facts that may assist a court in finding substitute service appropriate on a foreign company. Whether the district court was ultimately correct may likely not be resolved until after the case is decided and if Aputure appeals this decision.

Today marks a significant milestone for Irwin IP as we proudly celebrate our 10th anniversary!

Founded by Barry Irwin in 2014, Irwin IP has been litigating mission-critical, high-profile intellectual property and technology matters in federal courts across the country. Over the past decade, our journey has been defined by unwavering dedication and innovation. We are grateful for the trust and partnerships we’ve built with our clients, colleagues, and the communities we serve.

Thank you to our exceptional team for their hard work, commitment, and, most importantly, passion. Together, we’ve achieved remarkable milestones and shaped the success of Irwin IP. We look forward to many more years of serving our clients with the highest standards of professionalism and integrity.

During the last 10 years, Irwin IP has worked on and been involved in major litigation matters on behalf of its clients, including:

- Being the first firm in more than 6 years to successfully seek an en banc rehearing before the entire Federal Circuit and the first to have an en banc hearing granted in a design patent case in more than 16 years;

- An offensive patent infringement action, winning a $7.3 million jury verdict, and obtaining a permanent injunction protecting a $100-million-per-year product line;

- A $500 million, multi-patent infringement defense, winning a complete defense jury verdict

- Numerous expedited intellectual property litigation matters for industry leading gaming companies wherein preliminary injunctions and consent judgments have been obtained involving a diverse range of technology;

- Numerous successful copyright infringement matters for recording artists, photographers and sculptors wherein Irwin IP has enjoining unlawful distribution of infringing works.

——–

Irwin IP specializes in mission-critical intellectual property and technology litigation, catering to a diverse client base, including Fortune 500 companies and innovative startups. Our expertise extends to enforcing and protecting intellectual property portfolios, ensuring our clients’ product lines, worth hundreds of millions annually, remain secure. Notably, we routinely, successfully litigate against the largest, most prestigious law firms representing the largest companies in the world on matters valued in the tens and hundreds of millions.

In an opinion made precedential at the PTAB’s request, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) affirmed a PTAB determination that a trademark application for the wordmark “EVERYBODY VS. RACISM” committed a “cardinal sin” under the Lanham Act by undermining the source-identifying function of a trademark. The Act conditions the registration of any mark on its ability to identify and distinguish the goods and services of the owner from those of others. Still, the PTAB found, and the CAFC agreed, that this mark was not source-identifying and instead co-opted political expression.

On June 2, 2020, Go filed its application on “EVERYBODY VS. RACISM” for use on such goods as tote bags, T-shirts, and other clothing, as well as services such as “[p]romoting public interest and awareness of the need for racial reconciliation.” The examiner rejected the application, reasoning that the mark failed to function as a source identifier for Go’s goods and services. Rather, the examiner found that the mark was an informational social or political message that merely conveys support for or affiliation with the ideals conveyed therein. The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board affirmed.

On appeal, the CAFC reiterated that what makes a trademark a trademark is its source-identifying function, and this inquiry is not just limited to just determining whether the mark is generic or merely descriptive. What matters is how the mark is used and what consumers in the market perceive the mark to mean. The CAFC reasoned that a mark is not registerable if consumers do not perceive the mark as source-identifying and such unregistrable marks include those comprising of “informational matter,” such as slogans or phrases commonly used by the public.

The examiner found extensive use of the claimed phrase on clothing items by third parties in an informational and ornamental manner to convey anti-racist sentiments. Further evidence showed that the phrase frequently appeared in opinion pieces, music, podcasts, and organizations’ websites in support of efforts to eradicate racism. Notably, Go did not dispute that those uses were not its own. Instead, Go argued that the mark had rarely been used before it began to use it, and that its “successful policing” of the mark led to a significant drop in web searches for the mark (notably achieving the opposite of ‘raising awareness,’ a purpose for which Go claimed the mark in its trademark application). The CAFC affirmed the Board’s findings as supported by the evidence and rejected Go’s appeal on the basis that Go merely sought that the CAFC re-weigh the evidence considered by the Board (which it would not do).

Go further argued that the Board’s “per se” refusal of its application on the basis that it claimed informational matter is unconstitutional as a content-based restriction on speech not justified by a compelling or substantial governmental interest. The CAFC found this argument meritless and grounded in the faulty premise that the PTO’s reliance on the informational matter doctrine results in per se refusals regardless of whether the mark is source-identifying or not. Additionally, the CAFC reasoned that there are widely used slogans that nonetheless function as source identifiers, for example, “TRUMP TOO SMALL,” which the CAFC reversed the Board’s refusal to register the mark and held the board’s decision to be unconstitutional.

As the dust settles, it is clear that while the PTO allows trademarks on phrases and slogans, it will only do so if the phrase or slogan is source-identifying. Contrary to Go’s argument, however, barring trademarks on political expression is not an unconstitutional impingement on free speech. Gating the free expression of political ideas behind trademark monopolies and licensing fees, however, would impinge on free speech.