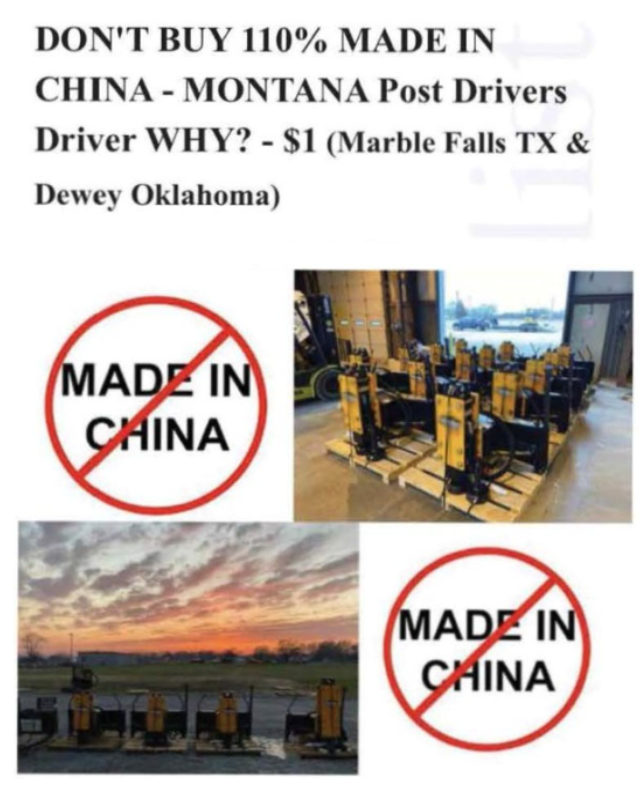

On April 12th, the 10th Circuit determined that I Dig Texas’ (“IDT”) use of the term “American-made” to promote its products and to discourage consumers from supporting its competitor, Creager, is inherently ambiguous. Thus, advertisements including that phrase for products assembled in the United States using components from other countries were not literally false under the Lanham Act. The 10th Circuit also affirmed no indirect copyright infringement damages were available to Creager for the use of its copyrighted images in IDT’s ads because Creager was unable to prove a nexus between IDT’s sales and its ads using the infringed photos. As such, the 10th Circuit granted summary judgment in favor of IDT on both Creager’s false advertising and copyright counterclaims and remanded the case to state court for a determination of the state law claims.

The Court considered whether IDT’s ads, bearing the words “Made in America,” and American flags, constituted false advertising. Under the Lanham Act, a claimant may show falsity in one of two ways: (1) when a statement is literally false, or (2) when a statement is literally true, but “likely to mislead or confuse customers.” The statement must be unambiguous to be literally false, meaning if a statement is susceptible to more than one reasonable interpretation it cannot be literally false. Creager only argued the ads were literally false and not that the ads were misleading. To determine whether IDT’s statement was “literally false,” the court asked, “what does it mean to make a product in the United States or in America?” The Court concluded that the term “make” was susceptible to more than one meaning. It could either refer to the origin of the components or the location of assembly of the product itself. Similarly, use of patriotic symbols is also ambiguous since the symbols may imply that the products are American-made, but this cannot be objectively verified as true or false.

The Court further affirmed summary judgment to IDT on Creager’s copyright counterclaims for the use of copyrighted images of Creager’s products next to a “Made in China” symbol, focusing on whether Creager could prove a nexus between IDT’s sales and use of the infringed images. The District Court granted summary judgment to IDT finding that IDT’s use of the images in comparative advertising was permissible fair use without reaching the nexus issue. The 10th Circuit did not address fair use and held there was no nexus because no evidence was presented that IDT sold any additional products due to its ads containing Creager’s copyrighted product photos.

This decision highlights the importance of pleading both “literal falsity” and “true, but likely to mislead” in false advertising cases, as well as the desirability of registering images prior to use in commerce for the availability of statutory damages in copyright infringement matters.

Patents are prohibited from claiming inventions that would have been obvious to a person having ordinary skill in the art (“POSITA”). This non-obviousness requirement is an application of the Constitution’s limitations on the scope and purpose of Congress’ authority to grant patents.

Congress’ power to award patent monopolies flows from Art. I, § 8, cl. 8 of the Constitution, which states: “Congress shall have Power … to promote the Progress of Science and Useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” “This clause is both a grant of power and a limitation” that “was written against the backdrop of the practices … of the Crown in granting monopolies to court favorites in goods or businesses which had long been enjoyed by the public.” Graham v. John Deere, 383 U.S. 1, 5 (1966). In other words, the Constitution forbids patents on obvious subject matter because they would not “promote the Progress of Science and the Useful Arts.”

As Graham made clear, Clause 8’s limiting language is no paper tiger:

Congress in the exercise of the patent power may not overreach the restraints imposed by the stated constitutional purpose. Nor may it enlarge the patent monopoly without regard to the innovation, advancement[,] or social benefit gained thereby. Moreover, Congress may not authorize the issuance of patents whose effects are to remove existent knowledge from the public domain, or to restrict free access to materials already available. Innovation, advancement, and things which add to the sum of useful knowledge are inherent requisites in a patent system which by constitutional command must ‘promote the Progress of * * * useful Arts.’ This is the standard expressed in the Constitution and it may not be ignored.

Id. (quoting U.S. Const., Art. I, § 8, cl. 8). Patent monopolies on obvious subject matter add no knowledge to the public domain, but rather remove existent knowledge, and undermine the Constitutional purpose of patents—promoting progress in the useful arts. KSR Intern. Co. v. Teleflex, 550 U.S. 398, 416 (2007).

While the first Patent Act, passed in 1790, did not contain any express requirement of non-obviousness, it did require that certain high-ranking government officials assess whether an invention was “sufficiently useful and important” to merit a patent. 1 Stat. 109-112, § 1 (Apr. 10, 1790). This examination criterion was intended to exclude frivolous and obvious patents. However, this requirement proved problematic because such officials lacked time to examine patents (resulting in a backlog). In 1791, Jefferson drafted a revised Patent Act dispensing with examination and the “sufficiently useful or important” criterion, substituting it with a provision for alleged infringers to challenge patents by proving them “so unimportant and obvious that it ought not to be the subject of an exclusive right.” The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 5 at 279 (Feb. 7, 1791). However, Congress took no action on the draft bill that year, and upon resubmission the following year, the bill, after extensive revision, was passed as the Patent Act of 1793. This Act dispensed with examination1 and the requirement that inventions be “sufficiently useful and important,” as Jefferson had proposed, but did not incorporate the provision for invalidating obvious patents.

Following enactment of the Patent Act of 1793, some courts rejected the idea that there was any requirement for patentability beyond novelty and usefulness. See, e.g., Earle v. Sawyer, 8 F.Cas. 254, 255 (D. Mass. 1825) (rejecting any prohibition on obvious patents). However, in 1850, in Hotchkiss v. Greenwood, the Supreme Court recognized that patentability required more than what the ordinarily skilled artisan could envision. See 52 U.S. 248, 267 (emphasis added):

unless more ingenuity and skill … were required … than were possessed by an ordinary mechanic acquainted with the business, there was an absence of that degree of skill and ingenuity which constitute essential elements of every invention. In other words, the improvement is the work of the skillful mechanic, not that of the inventor.

The dissent asserted that the requirement lacked any basis in precedent2. Id. at 26869 (J. Woodbury, dissenting). However, Hotchkiss’ holding aligns with Clause 8’s requirements that patents promote the progress of the useful arts by requiring a patent to disclose something more than what was already within the knowledge or creativity of the field. Indeed, Hotchkiss’ reference to the ordinary mechanic’s “ingenuity,” makes clear that the Court was focusing on not only the ordinary mechanic’s knowledge and skills, but their creativity and what they could envision.

As the Supreme Court in Graham and KSR later found, the “premises [underlying Clause 8] led to the bar on patents claiming obvious subject matter established in Hotchkiss and codified in § 103.” KSR, 550 U.S. at 427. The non-obviousness requirement did not emerge from the judicial ether; it was contemplated from the start and needed to align the patent system with its Constitutional purpose.

This week, the United States District Court for the Central District of California (the “Court”) granted L’Oreal’s motion for terminating sanctions. The litigation centers around L’Oreal’s alleged misappropriation of Metricolor’s trade secret, which is a first-generation system for storing, formulating, and dispensing hair coloring agents and additives. The system comprises of a “plastic bottle, a standard [] orifice reducer, and a syringe.” In 2014, Metricolor and its president, Sal D’Amico, discussed a few of its products with L’Oreal. The discussions centered around Metricolor’s second-generation product, but Metricolor alleged that, during its pitch, it related details of its first-generation system to L’Oreal. The discussions proved unfruitful, but in September of 2016, L’Oreal launched a product similar to Metricolor’s first-generation system. Metricolor brought suit in January of 2018.

In 2021, L’Oreal began to suspect that Metricolor had produced edited documents. For example, Metricolor appeared to fabricate an email exchange indicating that Metricolor sent L’Oreal samples of its first-generation system. However, the recipient of those emails did not recall ever seeing the email nor receiving any samples. Later, in October 2021, Metricolor’s own expert, Kevin Cohen, created a forensic image of Sal D’Amico’s computer (“Cohen Image”), unbeknownst to L’Oreal or the Court. L’Oreal, unaware of the Cohen Image, filed an ex parte application to suspend deadlines pending investigation of documents. The Court denied the application, but ordered L’Oreal to take a forensic image (“L’Oreal Image”) in December 2021, of the same computer previously imaged by Cohen. L’Oreal noted that several sample documents contained deletions and insertions when compared to what Metricolor had produced in the litigation. L’Oreal unsuccessfully sought terminating sanctions. However, in March 2023, Mr. Cohen disclosed creation of the Cohen Image, which the Court compelled Metricolor to produce. When comparing the Cohen and L’Oreal Images, more than fifty thousand files were missing from the L’Oreal Image. L’Oreal’s renewed motion to terminate the case was successful.

The Court found that Metricolor’s actions were “troubling” and “easily support a finding of willfulness, bad faith, and fault.” First, the Court stated that it is entirely unclear whether Metricolor ever disclosed the trade secret that was subject to the litigation, because the “limited evidence suggesting the existence and conveyance of a trade secret was largely fabricated.” Second, the Court stated that such an ambiguity would be prejudicial because L’Oreal was deprived of important evidence. Finally, the Court found that lesser sanctions would not be appropriate here because monetary or adverse inference sanctions would be insufficient to remedy the impact or deter future misconduct if the case was allowed to proceed.

This case serves as yet another warning to counsel representing zealous clients. Although the Court directed most of its ire toward “particularly Sal D’Amico[,]” who fabricated and destroyed evidence, counsel’s behavior was also problematic because they improperly withheld responsive discovery after the Cohen Image was discovered. Even if a client believes their efforts are justified to get the truth out, it is the duty of counsel to trust-but-verify and ensure that all conduct is unquestionably above board. Else, parties risk losing over six years of litigation efforts.

As an initial disclaimer, Irwin IP LLP is privileged to be lead counsel for LKQ Corporation and Keystone Automotive Industries, Inc. (collectively, “LKQ”) in several design patent validity disputes, including this case against GM Global Technology Operations and by extension General Motors Co. (collectively, “GM”). LKQ neither requested nor paid for preparation of this article, however, and the views expressed herein are those of the authors alone.

Last month, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”), held an en banc oral argument for LKQ’s appeal of the Inter Partes review decision by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) which held that U.S. Design Patent No. D797,625 (“the ’625 Patent”) was not unpatentable as obvious. During the US Government’s argument, Judge Chen broached a central issue of the appeal when he asked whether it was “true that only about one to two percent of all design patent applications get a prior art rejection during examination?” The Government indicated that their rate is “a little higher,” but admitted that only “about 4%” of design patent applications receive a prior art rejection. This low rejection rate for design patents has received the attention of design patent scholars. See Sarah Burstein, Is Design Patent Obviousness Too Lax?, 33 BERKELEY TECH. L. J. at 608-610, 624 (2018) (positing that design patent validity precedent makes it nearly impossible for the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) to reject design patent claims); Dennis Crouch, A Trademark Justification for Design Patent Rights, 24 HARV. J. L. TECH. at 18-19 (2010) (citing the “vastly different” rejection rate between design and utility patents as evidence that the USPTO has abdicated its role in examination for design patents). For reference, by some estimates, the amount of total rejections for utility patents under prior art (35 U.S.C. §§ 102, 103) is as high as 68%.1 An important component of this explanation is that design patents have not received the flexible and expansive obviousness inquiry mandated by the US Supreme Court’s KSR decision.

In an effort to explain the low rejection rate, GM referred to an amicus brief submitted by Hyundai Motor Company and Kia Corporation (“Hyundai-Kia”), arguing that “often these, these design patents, because it’s a singular claim, you will see, for example, a shoe will be patented once and then you’ll see, you know, more patents off that similar initial concept. So, there’ll be a lot of patents that come out of the same invention because you can’t have, you know, 25 claims.” GM also argued that “the narrowness of design patents is another reason why we see a difference in the allowance rate as compared to utility.” Neither Hyundai-Kia nor GM cited any support for their theories. This article shows that neither argument adequately explains the alarmingly low rate at which design patents receive prior art rejections.

Regarding the argument that multiple design patents are filed on the same invention, there is no explanation as to why that would drive down the rejection rate. Logically, if there are groups of design patents for a particular invention (a “design patent family”) one would expect that prior art applicable to one patent in the family would be applicable to all of the patents in the family. And, one would expect that the number of design patent families that receive a prior art rejection as compared to the total number of design patent families would mirror the rate individual design patents receive a prior art rejection as compared to the total number of individual design patents. As such, the fact that there may be design patent families should not impact the overall rejection rate. Further, dissecting a whole design into many component elements (“design patents on fragments”) would likely seem to create a higher probability that any of these elements would have been known in the art to an ordinary designer. And, as such design patents on fragments would logically seem to drive up the rejection rate.

Regardless, it is appropriate to stress test the effect “duplicate design patents” could have in skewing the prior art rejection rate. By randomly selecting tranches of 50 sequential design patents granted between 2013 and 2023, we can create a statistically significant subset of design patents (that demonstrates the same 2-4% prior art rejection rate overall) to identify the percentage of design patents that were, as GM and Hyundai-Kia have argued, multiple, narrowed claims of the same invention. By removing these patents from the analysis altogether, we can determine an adjusted rejection rate for just individual design patents. For example, assuming no patent applications that received a prior art rejection were issued, if we were to hypothetically apply a 4% rejection rate to our sample of 500 patents, we can determine that about 21 patents were rejected to result in 500 allowed patents. If within those 500 patents, there are 50 duplicate design patents, that would leave 450 individual design patents. Dividing the rejected patents by just the individual design patents leads to an adjusted rejection rate. In our example, the adjusted rejection rate (21/450) is 4.67%. In performing our analysis, to be as generous as possible to GM and Hyundai-Kia’s argument, we also calculated an adjusted percentage by including similar designs issued to the same entity.

Applying this methodology, only 8.6% of design patents are duplicate patents in the way that GM and Hyundai-Kia argue. Removing these from the randomized subset, 91.4% of the design patents remain. Applying the Government’s 4% prior art rejection rate against the sample that excludes the duplicate patents, we arrive at an adjusted prior art rejection rate of 4.37% (still “about 4%”). If we expand the definition of duplicate design patents beyond GM and Hyundai-Kia’s definition in the above-mentioned manner, there are a total of 15.2% duplicate design patents. Once these are excluded and we are left with 84.8% of the randomized subset, applying the Government’s 4% prior art rejection rate results in an adjusted prior art rejection rate of 4.7%. At bottom, the exclusion of duplicate design patents in the way that is most generous to GM and Hyundai-Kia’s argument does not raise the prior art rejection rate of design patents by even one percentage point. The existence of duplicate design patents fails to explain the alarmingly low rate at which design patents receive prior art rejections.

Although not specifically argued by GM or Hyundai-Kia, the scholarly community should consider whether a claim-by-claim analysis of utility patents would result in a prior art rejection rate of about 4% for individual patent claims. That is beyond the scope of this article, but based on the readily available data we hypothesize that such a prior art rejection rate would still be “vastly different.”

Finally, GM’s appeal to design patent “narrowness” does not provide design patents with any kind of conceptual armor. The adage that “design patents have no scope” due to their visual claim style, has been practically rejected by modern precedent. See, e.g., Crocs, Inc. v. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 598 F.3d 1294, 1304-06 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (finding that several products with noticeable differences read on a single design patent, effectively expanding its scope beyond the literal claim depicted). Many courts have found that design patents have expansive scope in terms of infringement and damages.

The CAFC’s attention to the issue of the alarmingly low design patent prior art rejection rate at oral argument was well placed. As shown above, the disparity of this rate with that of utility has not been reconciled by any explanation or argument and is probably indicative of an inability or acquiescence to rigorous examination on the part of the USPTO.

- https://projectpq.ai/patent-rejections-103 ↩︎

A license agreement with broad terms might seem like a good idea, but it could turn into something that you later regret. On March 25, 2024, the Second Circuit (“the Court”) affirmed that a licensee did not violate a trademark license agreement for “beer” products by selling hard seltzer products under the same trademark.

Cervecería Modelo de México, S. de R.L. de C.V. and Trademarks Grupo Modelo, S. de R.L. de C.V. (collectively, “Modelo”) entered into a perpetual trademark license agreement with CB Brand Strategies, LLC, Crown Imports LLC, and Compañía Cervecera de Coahuila, S. de R.L. de C.V. (collectively, “Constellation”) for Constellation to use Modelo’s trademarks to make and sell “beer” inside the United States. The license agreement defined “beer” as “beer, ale, porter, stout, malt beverages, and any other versions or combinations of the foregoing, including non-alcoholic versions of any of the foregoing.” Recently, Constellation started to sell Corona Hard Seltzer and Modelo Ranch Water (collectively, “Corona Hard Seltzer”) using Modelo’s trademarks. Corona Hard Seltzer is a flavored carbonated drink that derives its alcohol content from fermented sugar. Modelo sued Constellation alleging that sales of Corona Hard Seltzer violated the trademark license agreement because Modelo believed a sugar-based hard seltzer did not constitute “beer” under the license agreement. The issue of what “beer” meant was sent to a jury who determined that Modelo failed to establish that hard seltzer was not beer as defined in the license agreement. Modelo appealed.

On appeal, Modelo argued that under the plain meaning and dictionary definitions of “beer” or “malt beverages” that Corona Hard Seltzer could not be a beer or malt beverage because the seltzer was not flavored with hops and contained no malt. The Court acknowledged that the plain and ordinary meanings of “beer” and “malt beverages” would exclude Corona Hard Seltzer, however, the definition of “beer” allowed for “versions” of beer and malt beverages. Modelo argued “versions” could only mean beverages sharing similar characteristics to beer or malt beverages. Constellation argued that the definition of “beer” also included “non-alcoholic versions” and that a beverage without the common elements of beer, such as malt or hops, would be covered under the agreement. The Court held both parties’ definitions of the term “versions” were plausible and that the definition of “beer” was ambiguous as to whether it included Corona Hard Seltzer. Therefore, the Court affirmed the jury’s determination that “beer,” at least as used in the license agreement, included hard seltzers as the jury was not limited to plain and ordinary meaning of the term and was allowed to consider the parties’ intent when the contract was negotiated.

IP owners need to be careful using license agreements with broad definitions, like “any other versions” used here, because those definitions may later include items the IP owner did not intend to include at the time of the agreement. If there is any uncertainty in the scope of an IP contract, the ambiguity may be used against the IP owner in the future.

On February 28, 2024, in AlexSam, Inc. v. MasterCard International Incorporated, the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s summary judgment in favor of MasterCard and remanded. The Federal Circuit found that AlexSam could maintain its suit because the covenant not to sue provision in the License Agreement (“Agreement”), which the lower court relied upon in granting summary judgment, had terminated. Thus, the Federal Circuit held that AlexSam’s claim for breach of the Agreement’s royalties provision was not barred by the covenant not to sue.

The Agreement between the parties, regarding “Multifunction Card System” patents owned by AlexSam, included a covenant not to sue in which AlexSam agreed to “not at any time initiate, assert, or bring any claim against MasterCard…relating to Licensed Transactions arising or occurring before or during the term of this Agreement.” In 2015, AlexSam sued MasterCard for material breach of the Agreement and for failure to pay royalties pursuant to the Agreement. MasterCard filed for summary judgment, arguing the broadly worded covenant not to sue barred AlexSam’s claim for unpaid royalties. The district court agreed and granted summary judgment to MasterCard.

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s decision, observing that the broad, plain language of the covenant meant that AlexSam cannot bring suits for patent infringement or breach of contract actions during the time when the Agreement was in force. However, at the time of the suit the Agreement had terminated. Although the Agreement included sections that would survive termination of the Agreement, including the duty to pay royalties, it did not list the covenant not to sue as one. Even though the covenant not to sue had in perpetuity language (“at any time”) and could be interpreted as such between two sophisticated parties, the Federal Circuit found that the language only held weight during the term of the Agreement and not post-termination. Therefore, the covenant not to sue terminated with the Agreement, and AlexSam would be allowed to maintain its suit for nonpayment of royalties against MasterCard.

As Judge Stoll states, this matter “illustrates the importance of carefully reviewing the language in a covenant not to sue.” Drafters of license agreements, if they intend any provision to survive the agreement’s termination or expiration, should be careful to explicitly include the provision in the termination provisions of the agreement.

On February 9, 2024, in Rai Strategy Holdings Inc. v. Philip Morris Products S.A., the Federal Circuit vacated the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s (PTAB) finding that claimed ranges of length rendered Rai’s vape device claims invalid for lack of written description. The Federal Circuit rejected Philip Morris’ rigid argument that the claims lacked written description support because the specification did not identify the specific claimed range. The Court found the claims not invalid because the claimed range was within a broader range disclosed in the specification and there was no evidence that the claimed ranges resulted in a different invention than what was disclosed.

The written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112 requires that a patent’s specification include sufficient detail to reasonably convey to a person of ordinary skill that the inventor had possession of what is claimed. Rai’s patent disclosed heating element-to-disposable aerosol ratio ranges between 75%-125%, 80%-120%, 85%-115% and 90%-110%. Rai’s claims at issue, however, recited a subrange between 75%-85%. The PTAB had found that the claims lacked written description support because no range described in the specification contained an upper limit of about 85%.

In reviewing the PTAB’s decision, the Federal Circuit explained that evaluating whether there is written description support for a claimed range involves not just comparing the claimed range with those disclosed in the specification, but also whether the disclosed broad ranges describes the subrange or whether the subrange is drawn to a different invention. This is especially true in complex or unpredictable technologies where the invention may have different characteristics across the broader range. The Federal Circuit held that there was no evidence suggesting that the broader ranges described in Rai’s patent specification disclosed a different invention than the claimed range. The Court also stated that given the lack of complexity of the claim limitation at issue—heating element length—a lower level of detail was required. The Court vacated the PTAB’s decision, but noted that its determination was highly factual and dependent on the nature of the invention and the disclosure.

Patent prosecutors should be aware of the written description requirement as it relates to claiming ranges in patent applications. If a claim is amended to overcome prior art by narrowing a claimed range, a written description problem may arise if the new range does not fall within a broader range described in the specification or if the characteristics and behaviors of the invention vary across the disclosed broader range. Likewise, Rai provides a helpful roadmap to litigators challenging or defending written description support of claimed subranges.

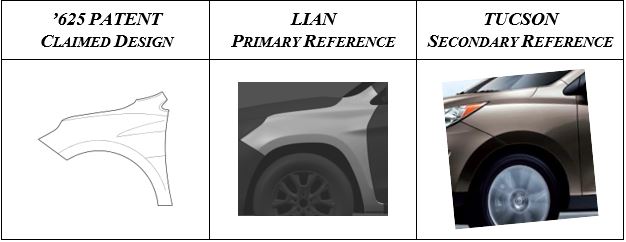

As an initial disclaimer, Irwin IP LLP is privileged to be lead counsel for LKQ Corporation and Keystone Automotive Industries, Inc. (collectively, “LKQ”) in several design patent infringement matters, including this case against GM Global Technology Operations and by extension General Motors Co. (collectively, “GM”). However, LKQ neither requested nor paid for preparation of this article, and the views expressed herein are those of the authors alone. Last year, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”), agreed to rehear en banc LKQ’s appeal of the Inter Partes review decision by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) which held that U.S. Design Patent No. D797,625 (“the ’625 Patent”) was not unpatentable as obvious. This marked the first time that the CAFC granted such a petition in a patent case in over five years—or 15 years for a design patent case.

The current design patent obviousness analysis, the Rosen–Durling test (named for In re Rosen and Durling v. Spectrum Furniture), is the crux of the dispute. Rosen–Durling restricts the obviousness analysis for design patents unless a patent challenger can show that there is a single primary reference that is basically the same as the patented design and any secondary references used in combination with that “Rosen reference” must be “so related in appearance” so as to suggest their combination. LKQ argues that both prongs of this test constitute rigid rules that prevent courts and the patent office from considering what a designer of ordinary skill in the art (“DOSA”) would have found obvious. Rosen–Durling would therefore be inconsistent with the United States Supreme Court’s decisions in KSR v. Teleflex and Smith v. Whitman Saddle, 35 U.S.C. §103 (which governs the obviousness requirement for all patents), and the Intellectual Property Clause of the United States Constitution.

Ten of the active judges sitting on the CAFC, Chief Judge Moore, and Judges Stark, Hughes, Taranto, Prost, Lourie, Dyk, Reyna, Chen, and Stoll, heard oral argument from LKQ, GM, and the United States Government on Monday, February 5, 2024. Generally, GM advocated for the opposite of LKQ’s position, and the Government argued in favor of relaxing the Rosen step and abandoning the Durling step. The Judges’ questions and comments at oral argument seem to indicate that a change to design patent obviousness law may be on the horizon.

The PTAB found LKQ’s primary reference (“Lian”) failed to satisfy Rosen’s gating requirement that it be “basically the same” as the claimed design. Several judges suggested that, if so, the threshold was too demanding. Chief Judge Moore, for example, remarked “I look at both of these and they certainly give me the same visual impression….” And later: “I look at these things—no difference.” Judge Chen similarly noted: “they do look sort of the same, right? Lian and the claimed design?” And, following up on Judge Prost questioning the credibility of one of GM’s arguments, Judge Stark queried “how could either of those saddle references [in Whitman Saddle] be a Rosen Reference if the Lian reference here is not?” He continued: “if somebody tried to count the differences between the two references in Whitman Saddle and the claimed design, you would easily get to more than seven, starting with the fact that it’s a front-half, back-half situation…. I’m not sure how this is a credible argument.”

Doctrinally, the judges had even more to say about Rosen–Durling. Judge Chen questioned “the source of the legal authority the Rosen court had to articulate the basically the same command for a primary reference?” He commented: “there was no case before Rosen that mandated that requirement or articulated any version of that, certainly not the Supreme Court, and we know it’s not in the statute.” Then, Judge Dyk asked “…isn’t it true that neither Rosen nor Durling discussed Whitman Saddle?” When GM confirmed they did not, Judge Dyk noted that was “a problem.”

Indeed, some judges questioned how different the current obviousness test is from anticipation. Chief Judge Moore expressed concern with GM’s argument that a more sophisticated designer is less likely to find something basically the same: “you told me that, for example, in this art … it’s a sophisticated art with a lot of prior art, so designers are very attuned to the nuances and the differences. So that means you can get a patent on something an ordinary observer would have absolutely said is the same thing. … But that means you get infringement damages against people when the very same thing or very similar things may have been in the prior art and the ordinary designer, much more sophisticated, would have allowed you to get your patent. What do we do about that?”

It was clear by the judges’ questions regarding the analogous art doctrine, that they will consider this in any potential change. Chief Judge Moore explained that in the utility patent context, the analogous art doctrine guides against the risk of hindsight infecting the obviousness analysis and posed several questions as to how the analogous art doctrine would work in the design patent context. Later, Judge Hughes gave an instructive hypothetical: “Say you have… furniture designers, …and they routinely look to what’s happening in contemporary architecture to import designs from architecture to furniture. Wouldn’t that be something you could look to even though a design for a building is certainly not remotely in the same endeavor as a furniture designer?” Chief Judge Moore endorsed this as “absolutely correct.” Interestingly, Chief Judge Moore and Judge Stoll, who asked the most questions about analogous art, previously decided Airbus v. Firepass which held that analogous art is a fact question that hinges on record evidence of “the knowledge and perspective of an ordinarily skilled artisan.” 941 F.3d 1374, 1383-84.

The CAFC asked several questions of LKQ and the Government on how the USPTO could apply a new design patent obviousness test. Judge Prost summed up the issue: “the PTO take[s] issue with your willingness or advocacy for abrogating the threshold test by saying that … in litigation you get the benefit of design experts, but the examiners don’t have that…” But Solicitor Rasheed also stated “we think that our examiners are capable, as they are in the utility side, and as they already do on the design side, to look at the prior art and to figure out … who the person of skill in the art is and to proceed from there.”

One final note, Judge Chen asked if it were “true that only about one to two percent of all design patent applications get a prior art rejection during examination?” The Government indicated that their rate is “a little higher” and clarified “about 4%” after questioning by Judge Stoll. This statistic, which is vastly different for utility patents, is said by Professor Sarah Burstein to demonstrate that CAFC precedent makes it nearly impossible for the Patent Office to reject design patent claims (and by Professor Dennis Crouch as evidence that the Patent Office has abdicated its role in examination). See Sarah Burstein, Is Design Patent Obviousness Too Lax?, 33 BERKELEY TECH. L. J. at 608-610, 624 (2018); Dennis Crouch, A Trademark Justification for Design Patent Rights, 24 HARV. J. L. TECH. at 18-19 (2010).

It remains to be seen what change in the law the CAFC will make and to what degree, but now more than ever, LKQ v. GM is a case worth following. Stay tuned for additional entries in this series that will explore other areas of interest in this case.

On January 26, 2024, the Federal Circuit denied a petition for writ of mandamus to vacate an order permitting Rotolight Limited (“Rotolight”) to serve Aputure Imaging Industries Co., Ltd. (“Aputure”) through email to Aputure’s in-house counsel.

Rotolight and Aputure manufacture and sell LED lights used in photography and filmmaking. In June 2023, Rotolight filed a complaint in the Eastern District of Texas against Aputure, a China-based company, for patent infringement. Rotolight made several unsuccessful attempts to serve Aputure at a California address obtained from multiple online business databases that had the same zip code as an office listed on Aputure’s website. In September 2023, Rotolight moved for substitute service pursuant to Texas Rule of Civil Procedure 106(b) to seek permission to serve Aputure by emailing Aputure’s legal counsel.

On October 16, 2023, the Eastern District of Texas granted Rotolight’s motion for substitute service to serve Aputure via email. The court found that Rotolight had attempted service enough times on Aputure at locations reported to be its place of residence in California and that service of the complaint and summons on Aputure’s in-house counsel’s email address would be effective to give notice to Aputure of the suit. In response, Aputure filed a petition for writ of mandamus to the Federal Circuit to vacate the order and deny the request for substituted service because service by email was improper and service should have been attempted through the Hague Convention since Aputure is based in China.

The Federal Circuit denied Aputure’s petition because Aputure failed to satisfy the three conditions in order to grant a writ of mandamus: (1) the petitioner must have “no other adequate means to attain the relief [it] desires,” (2) that the “right to issuance of the writ is clear and indisputable,” and (3) the court “in the exercise of its discretion, must be satisfied that the writ is appropriate under the circumstances.” For the first factor, Aputure did not show that a post-judgment appeal would be inadequate. For the second factor, Aputure did not demonstrate that it had a clear and indisputable right to relief. Although Aputure argued that the district court erred by refusing to require Rotolight to first attempt service of process in China pursuant to the Hague Convention, that argument failed because the district court appeared to have concluded Aputure could be served in California. Further, the Federal Circuit held district courts are given broad discretion to determine alternative means of service not prohibited by international agreement. For the third factor, the Federal Circuit ultimately determined that it was not prepared to determine that granting the motion was a clear abuse of discretion that warranted mandamus relief.

While a denial of the writ of mandamus does not determine whether the district court’s grant of the motion for substitute service was an abuse of discretion, this case demonstrates facts that may assist a court in finding substitute service appropriate on a foreign company. Whether the district court was ultimately correct may likely not be resolved until after the case is decided and if Aputure appeals this decision.

In an opinion made precedential at the PTAB’s request, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) affirmed a PTAB determination that a trademark application for the wordmark “EVERYBODY VS. RACISM” committed a “cardinal sin” under the Lanham Act by undermining the source-identifying function of a trademark. The Act conditions the registration of any mark on its ability to identify and distinguish the goods and services of the owner from those of others. Still, the PTAB found, and the CAFC agreed, that this mark was not source-identifying and instead co-opted political expression.

On June 2, 2020, Go filed its application on “EVERYBODY VS. RACISM” for use on such goods as tote bags, T-shirts, and other clothing, as well as services such as “[p]romoting public interest and awareness of the need for racial reconciliation.” The examiner rejected the application, reasoning that the mark failed to function as a source identifier for Go’s goods and services. Rather, the examiner found that the mark was an informational social or political message that merely conveys support for or affiliation with the ideals conveyed therein. The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board affirmed.

On appeal, the CAFC reiterated that what makes a trademark a trademark is its source-identifying function, and this inquiry is not just limited to just determining whether the mark is generic or merely descriptive. What matters is how the mark is used and what consumers in the market perceive the mark to mean. The CAFC reasoned that a mark is not registerable if consumers do not perceive the mark as source-identifying and such unregistrable marks include those comprising of “informational matter,” such as slogans or phrases commonly used by the public.

The examiner found extensive use of the claimed phrase on clothing items by third parties in an informational and ornamental manner to convey anti-racist sentiments. Further evidence showed that the phrase frequently appeared in opinion pieces, music, podcasts, and organizations’ websites in support of efforts to eradicate racism. Notably, Go did not dispute that those uses were not its own. Instead, Go argued that the mark had rarely been used before it began to use it, and that its “successful policing” of the mark led to a significant drop in web searches for the mark (notably achieving the opposite of ‘raising awareness,’ a purpose for which Go claimed the mark in its trademark application). The CAFC affirmed the Board’s findings as supported by the evidence and rejected Go’s appeal on the basis that Go merely sought that the CAFC re-weigh the evidence considered by the Board (which it would not do).

Go further argued that the Board’s “per se” refusal of its application on the basis that it claimed informational matter is unconstitutional as a content-based restriction on speech not justified by a compelling or substantial governmental interest. The CAFC found this argument meritless and grounded in the faulty premise that the PTO’s reliance on the informational matter doctrine results in per se refusals regardless of whether the mark is source-identifying or not. Additionally, the CAFC reasoned that there are widely used slogans that nonetheless function as source identifiers, for example, “TRUMP TOO SMALL,” which the CAFC reversed the Board’s refusal to register the mark and held the board’s decision to be unconstitutional.

As the dust settles, it is clear that while the PTO allows trademarks on phrases and slogans, it will only do so if the phrase or slogan is source-identifying. Contrary to Go’s argument, however, barring trademarks on political expression is not an unconstitutional impingement on free speech. Gating the free expression of political ideas behind trademark monopolies and licensing fees, however, would impinge on free speech.