The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the district court’s ruling that nonprofit digital library Internet Archive (“IA”)’s practice of scanning entire books and lending the e-books for free was not considered fair use under Section 107 of the Copyright Act, and thus, infringed the Plaintiffs-Appellees Hachette Book Group’s (“Hachette”) copyrights in 127 fiction and nonfiction books (the “Works”). IA’s “Open Libraries Project,” an alternative to print books and eBook licenses, is an archive that allows libraries to supply print books, excluding books published within the past five years, to be checked out. The Works at issue in the Open Libraries Project were not licensed from publishers, and the authors while compensated for the print books used for scanning, were not compensated for the digitization and distribution of their works. This case emphasizes that the conversion of copyrighted physical material for free digital distribution, even when done noncommercially and through a library lending model, is not protected by fair use.

In March 2023, the district court granted summary judgment to Hachette, reasoning that they established copyright infringement, and that IA did not have a fair use defense. The district court assessed the four statutory factors under Section 107: purpose and character of the use (whether the use was commercial and transformative), nature of the copyrighted work, amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole, and the effect of the use on the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. The district court concluded that IA’s use of the Works was not transformative because IA’s full reproduction of the Works served the same purpose as the originals in terms of making the Works available to read and IA’s solicitation of donations from physical book sales in connection to a link to a partner site embedded on IA’s website was commercially exploitative. Additionally, the district court found the remaining factors were also met.

The Second Circuit upheld the district court’s ruling, reasoning that IA’s digital copies of the Works only converted the format of the print books and failed to provide any new purpose or character to transform the original books. While the Second Circuit disagreed with the district court and assessed that IA’s use of the Works was not commercial in nature, it concluded IA’s work was not transformative. The Second Circuit found the second fair use factor favored Hachette because the Works were copyrightable, explaining that nonfiction books within the Works did contain subjective descriptions of facts and ideas by their authors. For the third fair use factor, IA undisputedly copied and distributed the Works to the public in full. Lastly, the Second Circuit agreed with Hachette there would be market harm, such as reducing potential licensing revenues and diminishing the incentive for consumers or libraries to pay publishers for digital content. The Second Circuit determined that such harm would outweigh the public benefit of the free digital library. Therefore, when weighing the factors together, the Second Circuit found each fair use factor favored Hachette.

While this may be a big win for publishers, it begs the question of how much control publishers will have over digital libraries and existing archives when facilitating e-book licenses, such as, determining the ratio for borrowing a digital book, the duration of the license, and at what price.

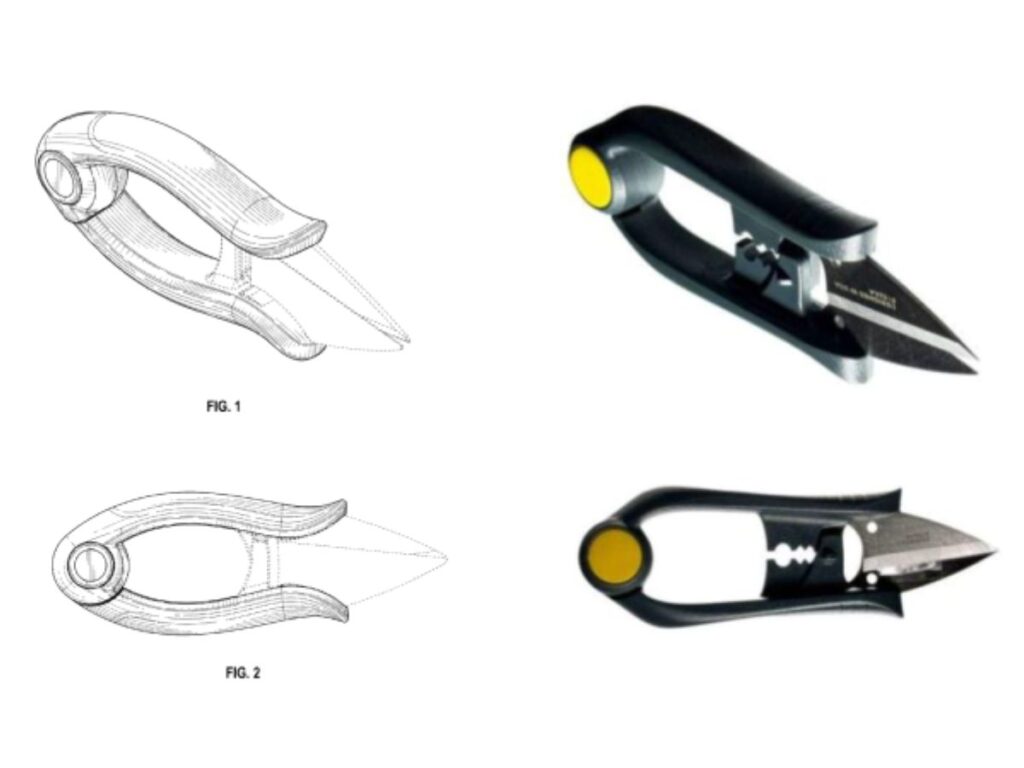

On August 26, 2024, the Western District of Wisconsin issued a decision adjudicating a number of motions in a case involving a thicket of intellectual property claims and counterclaims. Fiskars Finland OY AB and Fiskars Brands Inc. (collectively, “Fiskars”) sued Woodland Tools Inc. and its affiliated parties (“Woodland”), asserting design patent infringement, false advertising, trade secret misappropriation, and related state claims concerning the parties’ competing lines of gardening tools. Woodland counterclaimed for false advertising and tortious interference. The parties filed cross motions for summary judgment and motions to exclude expert opinions. The court significantly trimmed down the case, leaving for trial only a portion of Woodland’s false advertising counterclaim. A key part of the decision focused on the Court’s exclusion of Fiskars’ design patent expert.

The Court found three issues that rendered Fiskars’ expert’s opinion “unhelpful to the jury” and excluded it under Daubert. First, the expert used only a single piece of prior art, what he deemed “the closest,” in a three-way comparison of the accused product, the patented design, and prior art. The Court noted that “Egyptian Goddess contemplates that the prior art is likely to be a set of references,” and the expert’s use of only one reference “systematically understates the similarity of the patented design to the prior art, thereby improperly broadening the scope of protection for the patented design.” This is reminiscent of the Federal Circuit’s recent decision in LKQ Corp. v. GM Global Technology Operations LLC, where an en banc Federal Circuit held that KSR International Co. v. Teleflex, Inc. overruled the strict Rosen-Durling test for obviousness. The expert’s three-way infringement comparison using only a single reference, like in LKQ, “improperly broaden[ed] the scope of protection for the patented design.”

Second, the expert’s opinion misapplied functionality law. Any feature of a design that is “primarily functional” is not protected by a design patent. But the expert stated that a feature of the design is functional only if there is “only one” available design to serve that function. The expert made no further effort to see if the design encompassed both functional and ornamental elements or exclude any functional elements from his analysis. Finally, the opinion was too conclusory: the expert set forth a series of side-by-side images and then recited a conclusion without any explanation of how his comparisons related to his conclusion that the accused products infringed on the design patent.

In its 63-page opinion, the Court went on to, among other things, hold that “no reasonable jury could find that a hypothetical ordinary observer, familiar with the prior art, could find the accused product is substantially similar to the design claimed by the ’969 patent” (pictured) or to that in the ’828 patent.

This is at least the second case this year closely scrutinizing the scope of design patent protection vis-à-vis prior art. Parties dealing with design patents—both in prosecution and litigation—would do well to recognize the importance of assessing multiple prior art references in an evolving field of law.

We are pleased to announce that Bailey Sanders and Kyle Watson have officially joined Irwin IP as associates. Both Bailey and Kyle participated in our Summer Associate Program last year, where they demonstrated exceptional talent, dedication, and a strong passion for intellectual property law.

Bailey Sanders graduated from the University of Illinois Chicago School of Law, where he earned his J.D. and a certificate in Intellectual Property Law. Prior to law school, Bailey obtained a Bachelor of Science in Aerospace Engineering and Mechanics from the University of Alabama. During his time there, he served as an Environmental Controls Engineer on Project Veritas, contributing to the design and fabrication of an earth-based lunar rover.

Kyle Watson received his J.D. from DePaul College of Law. Prior to law school, he obtained a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering and a Master of Business Administration from the University of Missouri, Kansas City. Kyle brings valuable experience from his previous role as a USPTO Mechanical Examiner and his career in the architecture, engineering, and construction industry, specializing in virtual design for construction, parametric design, programming, and automation for manufacturing.

We look forward to the positive impact Bailey and Kyle will make at the firm.

——–

Irwin IP specializes in mission-critical intellectual property and technology litigation, catering to a diverse client base, including Fortune 500 companies and innovative startups. Our expertise extends to enforcing and protecting intellectual property portfolios, ensuring our clients’ product lines, worth hundreds of millions annually, remain secure. Notably, we routinely, successfully litigate against the largest, most prestigious law firms representing the largest companies in the world on matters valued in the tens and hundreds of millions.

On August 24, 2024, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) dismissed an appeal for lack of standing after a failed inter partes review (IPR) challenge by petitioner Platinum Optics Technology Inc. (Platinum Optics). The decision underscores the fact that even if a party has the right to challenge a patent before the PTAB, it might still lack standing to challenge the results of that action, risking an unappealable loss and, potentially, estoppel.

The dispute began when Viavi Solutions Inc. (Viavi) sued Platinum Optics for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,354,369 (the ’369 Patent), asserting claims related to optical filters. Platinum Optics filed an IPR before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) challenging the validity of the ’369 Patent. While the IPR was pending, the district court dismissed Viavi’s patent infringement lawsuit with prejudice. The IPR proceeded, however, and the PTAB subsequently upheld the patent’s validity. Platinum Optics appealed the decision to the CAFC. However, the CAFC found that, because Viavi’s patent infringement claims against Platinum Optics had already been dismissed with prejudice, Platinum Optics lacked standing to appeal because it could no longer demonstrate an “injury in fact.”

The incongruence of a party being able to pursue an IPR, but then being unable to appeal the result of that IPR is a result of the differing sources of authority under which IPRs and appeals arise. The PTAB is an executive agency, and proceedings before it, including IPRs, arise under Article I of the Constitution. If a party satisfies the statutory requirements, in this case 35 U.S.C. §§ 311 and 315, that party may challenge a patent via IPR. However, IPR appeals must be heard by the CAFC, which is an Article III court. Regardless of where the underlying case originated, an Article III court cannot adjudicate a case unless it satisfies the constitutional minimum of standing, which includes demonstrating an “injury in fact.”1

The CAFC has long held that an adverse IPR decision alone does not satisfy the requirement of an injury in fact.2 Platinum Optics argued that Viavi was likely to reassert the ’369 Patent because of Platinum Optics’ continued distribution of bandpass filters practicing the patent’s claims. The CAFC rejected this argument as too speculative to constitute an “injury in fact” (and it is not clear how this could be a real risk since Viavi’s claims that those products infringed were dismissed with prejudice). Platinum Optics’ assertions about future development plans were also deemed too vague and speculative.

The inability to appeal an IPR decision could place a challenger at a significant disadvantage if they are later sued for infringement, such as for a new product. The existence of an unfavorable PTAB determination would cast a shadow over any subsequent validity challenges. Worse, however, is the potential for estoppel. Under 35 U.S.C. § 315(e), a party that loses an IPR is estopped from raising in future litigation any grounds of invalidity that they “raised or could have raised” during the IPR. If estoppel applies, the challenger may be barred from further contesting the patent’s validity despite having had no opportunity to appeal the PTAB’s findings. From a literal reading of the statute, estoppel may attach even if the petitioner’s appeal was denied for lack of standing. See 35 U.S.C. §§ 315(e), 318. However, the only CAFC case addressing the issue cast doubt on attaching estoppel where the party could not appeal.3 Petitioners would be well-advised to look before they leap and consider whether they would have standing to appeal before pursuing an IPR.

On August 13, 2024, the Federal Circuit reversed a district court’s decision that a patent was invalid for obviousness-type double patenting (“ODP”) and held that In re: Cellect LLC, 81 F.4th 1216, 1228–29 (Fed. Cir. 2023) did not require the invalidation of a related earlier patent even though it expired later. ODP is a judicially created doctrine to prevent an inventor from receiving an unjustified timewise extension of an invention by filing multiple patents for the same invention but where each patent has different expiration dates. A patent owner can avoid ODP by filing a terminal disclaimer in the later expiring patent disclaiming any portion of the patent term that extends beyond the expiration of the earlier expiring patent. This case addressed what happens when the term of the earlier filed patent extends beyond the expiration of the later filed patent.

Sun Pharmaceutical Industries (“Sun”) filed an abbreviated new drug application (“ANDA”) for a generic version of Viberzi, which is covered by U.S. Patent No. 7,741,356 (“the ’356 patent”) owned by Allergan USA, Inc et al. (“Allergan”). Allergan then sued Sun alleging that Sun infringed the ’356 patent and two patents claiming priority to the ’356 patent: U.S. Patent Nos. 8,344,011 (“the ’011 patent”) and 8,609,709 (“the ’709 patent”). Of these patents, the ’356 patent was the first filed and first-to-issue, but due to a patent term adjustment (“PTA”) of 467 days, it was the last of these patents set to expire. Sun argued that the ’356 patent was invalid under ODP because it expired after the ’011 and ’709 patents. Allergan argued that ODP did not apply because the ’356 patent was filed first and issued first. That is, at the time the ’365 patent was being prosecuted, the inventor did not (and could not) know that the ’356 patent would expire after any other patents that it may file in the future. The district court, relying on Cellect, found that Allergan’s distinction was immaterial and invalidated the ’356 patent, finding that “[w]hen analyzing ODP, a court compares patent expiration dates, rather than filing or issuance dates.” Allergan appealed.

The Federal Circuit held that ODP cannot invalidate a first-filed, first-issued, later expiring patent. The Federal Circuit explained that Cellect held that PTA should be considered when analyzing ODP, but Cellect did not answer the question presented here—namely whether an ODP analysis is applicable to an earlier issued but later expiring patent. Analyzing the facts of this case, the Federal Circuit found that the ’011 and ’709 patents were not proper ODP references because they were later filed and later issued patents. ODP is meant to prevent an inventor from obtaining a second patent that is indistinct from the first patent to prevent the inventor from improperly extending the life of the first patent. Because the ’011 and ’709 patents were later filed and later issued, it was improper to use them in an ODP analysis to invalidate the earlier issued ’356 patent. Therefore, the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s decision.

After Cellect, there was concern that ODP would invalidate earlier filed, earlier issued patents in a patent family. This was problematic because when a patent is filed, its expiration date relative to later filed patents is unknown as PTA can vary for each patent and that it would be difficult for owners to monitor their patent families to determine when terminal disclaimers are needed. Although this case provides one instance where ODP does not apply, questions still remain regarding whether ODP is applicable in other situations.

Manufacturers beware! Your sales of products based on secret manufacturing processes may invalidate your patents. The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) recently affirmed an International Trade Commission (“ITC”) decision that invalidated process patent claims because the patentee sold products—manufactured based on the secret process claims—more than one year before the filing date of the patent.

Celanese International Corporation, Celanese (Malta) Company 2 Limited, and Celanese Sales U.S. Ltd. (collectively, “Celanese”) filed a petition in the International Trade Commission (“ITC”) against Anhui Jinhe Industrial Co., Ltd., and Jinhe USA LLC (collectively, “Jinhe”) arguing that Jinhe was importing into the United States sweeteners that were made using a process that infringed Celanese’s product-by-process patents. Jinhe moved for summary determination on the basis that Celanese’s process patent claims were invalid under the on-sale bar because Celanese sold a product that was secretly made using the claimed process more than one year prior to the effective filing date of Celanese’s patent. Celanese argued that its sweeteners, produced in secret, did not trigger the on-sale bar because the America Invents Act (the “AIA”) overturned pre-AIA precedent supporting that sales of products made in secret triggered the on-sale bar. The ITC agreed with Jinhe and held that Celanese’s process claims were invalid. Celanese appealed, arguing that (1) the AIA’s use of “claimed invention” and “otherwise available to the public” within Section 102 meant that Congress intended only processes which were publicly disclosed to trigger the on-sale bar, (2) Sections 102(b), 271(g), and 273(a) of the AIA changed the scope of the on-sale bar; and (3) the AIA’s legislative history indicated Congress wanted to protect an inventor’s secret commercialization of an invention. The CAFC rejected each of Celanese’s arguments.

First, the CAFC held that the use of the word “claimed” within the phrase “claimed invention” did not change the on-sale bar doctrine. The CAFC explained that the words “claimed invention” and “invention” are used interchangeably for the same invention and that there was no indication that Congress’s use of “claimed” changed the purpose of the on-sale bar doctrine. Additionally, the phrase “otherwise available to the public” does not require sales of the invention to explicitly disclose the process because this argument was explicitly rejected by the Supreme Court in Helsinn Healthcare S.A. v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., 586 U.S. 123, 139 S. Ct. 628, 202 L. Ed. 2d 551 (2019). The CAFC further held that Congress’s changes to Sections 102(b), 271(g), and 273(a) did not change the scope of the on-sale bar. Celanese argued that Section 102(b)’s grace period only applies to scenarios where the inventor disclosed the invention, but the CAFC rejected this argument because Celanese’s interpretation of Section 102(b) would put Section 102(b) at odds with Section 102(a)’s on-sale bar provision. Furthermore, the CAFC held that Sections 271(g) and 273(a) concern infringement and the actions of third parties and do not have any impact on the patentability provisions within Section 102. Finally, the CAFC rejected Celanese’s legislative history argument because a legislator’s views on what the AIA means is not enough to establish that Congress intended to modify the on-sale bar doctrine.

Businesses are often confronted with the dilemma to either protect their inventions as a trade secret or to seek patent protection. In this case, Celanese tried to have it both ways, but the CAFC was clear that businesses need to pick one or the other. If a business decides to protect a process as a trade secret for more than one year, the business may forfeit the ability to see patent protection over the process in the future.

On August 1, 2024, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals issued a ruling that affirmed a trade secret claim, but reversed and remanded a copyright claim related to Plaintiff Compulife’s insurance quote comparison software. First, the Eleventh Circuit reversed the district court’s decision, where the district court held that the Defendants did not infringe Compulife’s copyrights, because the lower court failed to consider whether the arrangement of the source code in Compulife’s software was copyrightable. Second, the Eleventh Circuit upheld the district court’s ruling that the defendants had misappropriated Compulife’s trade secrets by scraping its database. While scraping manually with no limitations for how many quotes pulled may be legal for obtaining publicly available information, it may be improper here because the defendants did not take screenshots of a publicly available site and instead, used another’s license to the software and a bot to take more than humanly possible.

Compulife’s software allows users to generate individualized quotes for life insurance comparison, using data from multiple insurance companies. The arrangement of the variables in its code must be arranged in a certain manner to work. Through improper means, the Defendants “copied the order of Compulife’s copyrighted code and used that code” to obtain millions of public and non-public variable-dependent quotes and created websites using the software, causing Compulife’s sales to decline.

First, the Eleventh Circuit addressed the copyright infringement claim. To establish copyright infringement, a plaintiff must prove: ownership of a valid copyright and copying the work’s original elements. For the first step, the Eleventh Circuit recognized that Compulife’s copyright was valid and undisputed. The second step of the analysis looked at two elements: factual copying (whether the defendant copied) and legal copying (whether those copied elements were considered protected expressions). Both the district court and Eleventh Circuit already determined factual copying. Later, the Eleventh Circuit broke down the code into its constituent structural parts, sifted out all non-protectable material, and compared the protected material with the copycat (the “abstraction-filtration-comparison test”) to evaluate legal copying. The Court observed that the district court only looked at the arrangement of some of the variables before filtering but failed to combine all the variables together in the arrangement. “[R]ecognizing the arrangement of elements of a program can be protectable [as a literal element of a program],” the Eleventh Circuit noted that the arrangement of the source code could be protected. The Eleventh Circuit remanded for further proceedings on that issue.

Next, the Eleventh Circuit analyzed whether the defendants misappropriated Compulife’s trade secret database of quotes via illegal acquisition, disclosure, or use. Here, the Eleventh Circuit determined that each of the defendants acted in concert to commit the trade secret misappropriation by “lying to get Compulife’s web quoter put onto his website,” supervising the scraping attack, investing in these fraudulent websites, and “collecting fees from insurance sales generated by the stolen trade secret.”

Overall, the Eleventh Circuit distinguished the improper versus proper way of scraping to obtain trade secrets, and this decision also emphasized the analysis of copyrightable elements in a work that district courts must perform to assess copyright infringement claims.

Irwin IP LLP is pleased to announce that four attorneys have earned recognition in the 2025 Edition of Best Lawyers: Ones to Watch.

Best Lawyers: Ones to Watch recognizes associates and other lawyers who are earlier in their careers for their outstanding professional excellence in private practice in the United States.

“Best Lawyers was founded in 1981 with the purpose of recognizing extraordinary lawyers in private practice through an exhaustive peer-review process. Nearly 40 years later, we are proud to expand our scope, while maintaining the same methodology, to recognize a different demographic of talented and deserving lawyers in Best Lawyers: Ones to Watch,” says Phil Greer, CEO of Best Lawyers.

Lawyers recognized in Best Lawyers: Ones to Watch are divided by geographic region and practice areas. They are reviewed by their peers based on professional expertise and undergo an authentication process to make sure they are in current practice and in good standing.

Irwin IP LLP would like extend congratulations to the following lawyers recognized in the 2025 Edition of Best Lawyers: Ones to Watch:

- Victoria Hanson – Intellectual Property Law, Litigation – Intellectual Property, and Litigation – Patent

- Alexa Tipton – Entertainment and Sports Law, Intellectual Property Law, and Nonprofit/Charities Law

- Nick Wheeler – Litigation – Patent

- Daniel Zhang – Intellectual Property Law, Litigation – Intellectual Property

We are proud of the talent and dedication our attorneys have demonstrated early in their careers. Their recognition in Best Lawyers: Ones to Watch is a testament to their commitment to excellence and the positive impact they continue to make in the legal field.

Irwin IP LLP is pleased to announce that four attorneys have earned recognition in the 2025 edition of The Best Lawyers in America®. Since it was first published in 1983, Best Lawyers has become universally regarded as the definitive guide to legal excellence.

“Best Lawyers was founded in 1981 with the purpose of highlighting the extraordinary accomplishments of those in the legal profession,” said Best Lawyers CEO Phillip Greer. “We are proud to continue to serve as the most reliable, unbiased source of legal referrals worldwide.”

Best Lawyers has earned the respect of the profession, the media, and the public as the most reliable, unbiased source of legal referrals. Its first international list was published in 2006 and since then has grown to provide lists in over 75 countries.

Lawyers on The Best Lawyers in America list are divided by geographic region and practice areas. They are reviewed by their peers based on professional expertise and undergo an authentication process to make sure they are in current practice and in good standing.

Irwin IP LLP would like to congratulate the following lawyers named to the 2025 The Best Lawyers in America list:

- Barry F. Irwin – Copyright Law, Litigation – Intellectual Property, Litigation – Patent, Patent Law, and Trademark Law

- Jason Keener – Litigation – Intellectual Property

- Robyn Bowland – Intellectual Property

- Reid Huefner – Patent Law

We are incredibly proud of the impact our attorneys have made, and we celebrate their dedication to excellence and the high standards they uphold in the legal profession.

On July 10, 2024, the Third Circuit vacated and remanded the district court’s decision to award attorneys’ fees to plaintiff Lontex, a sports apparel brand whose registered COOL COMPRESSION mark was used by Nike on its Nike Pro clothing line, finding that the district court’s determination that the case was “exceptional” was incorrectly rooted in broad policy considerations rather than facts specific to the case.

Lontex registered the COOL COMPRESSION mark with the United States Patent and Trademark Office in 2008 for athletic apparel. In 2015, Nike began using the phrase “cool compression” with its Nike Pro clothing. In 2016, Lontex demanded that Nike stop using Lontex’s mark on nike.com and with its distributors. Lontex eventually sued Nike claiming, among other things, that Nike was guilty of trademark infringement and contributory trademark infringement. Ultimately, the jury found Nike liable for willful and contributory infringement, and the district court granted Lontex’s request for treble damages and awarded Lontex attorneys’ fees of almost $5 million.

The Third Circuit affirmed the district court’s findings of willful and contributory infringement, as well as the punitive damages finding. However, the Third Circuit rejected the award of attorneys’ fees, finding that the district court failed to apply the facts to the correct caselaw and instead, relied on policy to justify its award of attorneys’ fees. More specifically, the district court justified its fee award based on the following reasons: (1) that the enforcement of trademarks is important; (2) that Lontex is a small company that took on Nike who has greater resources; and (3) that trademark cases are expensive to litigate, thus “as a matter of policy” it is unrealistic to expect a small company to pay for legal fees for this type of case.

The Third Circuit held that in order to support an award of attorneys’ fees, the case must be “exceptional” so that it “stands out from others with respect to the substantive strength of a party’s litigating position (considering both the governing law and the facts of the case) or the unreasonable manner in which the case was litigated.”1 The Third Circuit rejected the district court’s first reason—that enforcing trademarks is important—stating that this “truism does nothing to distinguish this case from any other trademark case.” Second, the Third Circuit rejected the district court’s “David and Goliath” matchup justification because it failed to provide additional evidence of Nike engaging in improper or unreasonable litigation tactics. Third, the Third Circuit found that the district court failed to address the possibility of Lontex receiving outside litigation funding when concluding that it is unrealistic for a small company like Lontex to pay the legal fees for this type of case. Finally, the district court’s brief mention of the substantive strength of Lontex’s case did not entail enough facts to find “exceptionality.” On remand, the district court was instructed to rely on the law outlined in Fair Wind Sailing, Inc. and Octane Fitness, LLC, and provide specific fact-based evidence to support its conclusion that this is an exceptional case justifying the award of attorneys’ fees.

Despite the district court’s compelling justifications for a finding of willful and contributory infringement, the lack of inclusion of those specific facts in determining the award of attorneys’ fees could not sustain the fee award on appeal. Accordingly, when arguing for attorneys’ fees, parties must emphasize the specific facts of their circumstances to prove “exceptionality” of their case. Bare policy considerations, although perhaps justified, will not support an award of attorneys’ fees.