The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) recently backed a Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“TTAB”) decision sustaining Barclays’ opposition to Tiger Lily’s attempted registration of a satirical LEHMAN BROTHERS mark for bar and restaurant services (in particular, for whiskey), and sunk Tiger Lily’s opposition of Barclays’ claim to the original LEHMAN BROTHERS marks.

Lehman Brothers, the LEHMAN and LEHMAN BROTHERS marks’ original owner, was once one of the largest investment banks in the United States. It also holds the dubious honor of having filed the largest bankruptcy in the nation’s history. Its cataclysmic failure marked the peak of the 2008 financial crisis. As part of Lehman Brothers’ dissolution, Barclays purchased the devalued marks, which it then allowed to expire. It was only in 2013, two months after Tiger Lily registered its own LEHMAN BROTHERS mark to market novelty alcohol products, that Barclays renewed the registrations. Tiger Lily and Barclays opposed each other’s applications before the TTAB, who bailed out Barclays’ marks and crashed Tiger Lily’s application. Tiger Lily appealed.

Tiger Lily first argued that Barclays had abandoned the LEHMAN marks by, among other acts, allowing the registrations to expire and publicly distancing itself from the liability that was the Lehman Brothers brand. However, Lehman Brothers had continued to use the marks in the winding up of its business and Barclays itself continues to provide legacy research materials with the marks. Thus, the CAFC found that Tiger Lily had failed to show nonuse of the mark, an essential element of trademark abandonment, notwithstanding the seemingly minor or residual nature of the use.

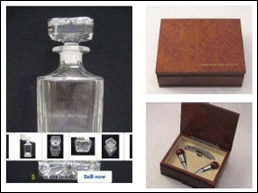

Tiger Lily further contended that there was no likelihood of confusion because its LEHMAN BROTHERS mark was associated with the bar and restaurant industry rather than financial services. The TTAB had nonetheless found a likelihood of confusion based on the general fame and notoriety of the bank’s marks. Numerous documentaries feature the marks prominently, as do a mountain of satirical references to the bank in media. These include a sign displaying “Bank of Evil (formerly Lehman Brothers)” in the animated film, “Despicable Me.” Moreover, collectors apparently put some stock in LEHMAN BROTHERS-branded memorabilia, which includes products like whiskey decanters and wine stoppers.

Thus, despite Tiger Lily’s evidence showing that its UK customers who had already consumed the products seemed aware of the joke and were not deceived or confused, the CAFC credited the TTAB’s finding that the marks were so famous as to encompass uses well beyond their original bubbles. Even if consumers were not confused into believing they were securing alcohol made by Lehman Brothers, Tiger Lily’s mark was backed by consumers’ recognition of the defunct bank’s name. Similarly, Tiger Lily’s theory that it was trading on “bad will” and infamy instead “good will” made no difference to the CAFC; the LEHMAN BROTHERS marks were entitled to the same protection as any other, notwithstanding their subprime reputation. At least in the world of trademarks, to be infamous is to be famous.