The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) recently upheld a decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) that found some claims of U.S. Patent 8,815,830 (“the ’830 patent”) unpatentable as anticipated. The ’830 patent’s owner, the Regents of the University of Minnesota (“Minnesota”), argued before the PTAB that the petition for inter partes review filed by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (“Gilead”) relied on a prior art reference that did not have priority over the ’830 patent. But the PTAB found that the ’830 patent’s priority claim to a sequence of patent applications that stretched back almost 20 years (the “priority applications”) lacked a written description sufficient to support the claim. Minnesota appealed the PTAB’s decision.

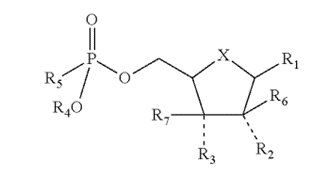

The ’830 patent was directed towards drugs that inhibit viral reproduction and the growth of cancerous tumors when they are metabolized by the human body. The first claim of the ’830 patent was a broad genus claim that covered many of these types of chemicals with the same general structure (shown right) including sofosbuvir, a drug developed by petitioner Gilead to treat hepatitis C infections.

Minnesota’s argument on appeal centered on the PTAB’s determination that the priority applications, in the broad outlines of their specifications, did not contain written description of chemicals claimed by the ’830 patent. In order to support a patent’s claim of priority and receive the benefit of an earlier filing date, an earlier patent application must “constitute a full, clear, concise and exact description” to a person having ordinary skill in the art. In re Wertheim, 646 F.2d 527, 538–39 (CCPA 1981). As in Fujikawa v. Wattanasin, an ipsis verbis, or literal prior disclosure is not required in every instance if a prior disclosure provides clear clues that “blaze a trail through the forest” and would lead an ordinarily skilled person precisely to a particular “tree” (technology) known as “blaze marks.” 93 F.3d 1559, 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1996).

The CAFC found that Minnesota had proposed a “maze-like” written description involving a littany of possibilities and alternate chemical paths with no indication as to what a skilled artisan would do beyond pure experimentation when they came to each branching path. This ruled out ipsis verbis written description disclosure, and the CAFC also found that Minnesota could not claim that these confusing proposals were blaze marks either, as the priority applications failed to point to the disclosure made in the prior art. The CAFC agreed that the priority applications, with enough roundabout steps through different chemical subgenera, would eventually lead to to the ’830 patent’s claims. But, they did not show structural features of the genus that would enable a skilled artistan to “visualize or recognize members of the genus” that were disclosed in the prior art. Ariad Pharms., Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336, 1350−52 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

Here, the CAFC reaffirmed that, in order to receive the benefits of an earlier-filed priority application, the priority application must particularly disclose the invention at issue—creative attorney argument attempting to link up the priority application with the claims of the patent will not suffice.