The Hatch-Waxman Act seeks to strike a balance in the pharmaceutical industry by incentivizing drugs makers to develop innovative drugs with additional patent protections while also providing shortened regulatory review procedures for generic drug manufacturers to rapidly get generic versions of the patented name-brand drugs to market after the expiration of the patents. The additional patent protections Hatch-Waxman provides includes patent term extensions (“PTEs”) of up to five years if FDA review of a new brand-name drug extends beyond the issuance of a patent covering the drug. A patent’s term generally lasts 20 years from the date it is filed. But, as the FDA’s review of a drug can take years, Hatch-Waxman seeks to compensate the patent owners of new drugs for the lost time on the market after (1) the patent had issued (2) but while the drugs were still held up in regulatory review.

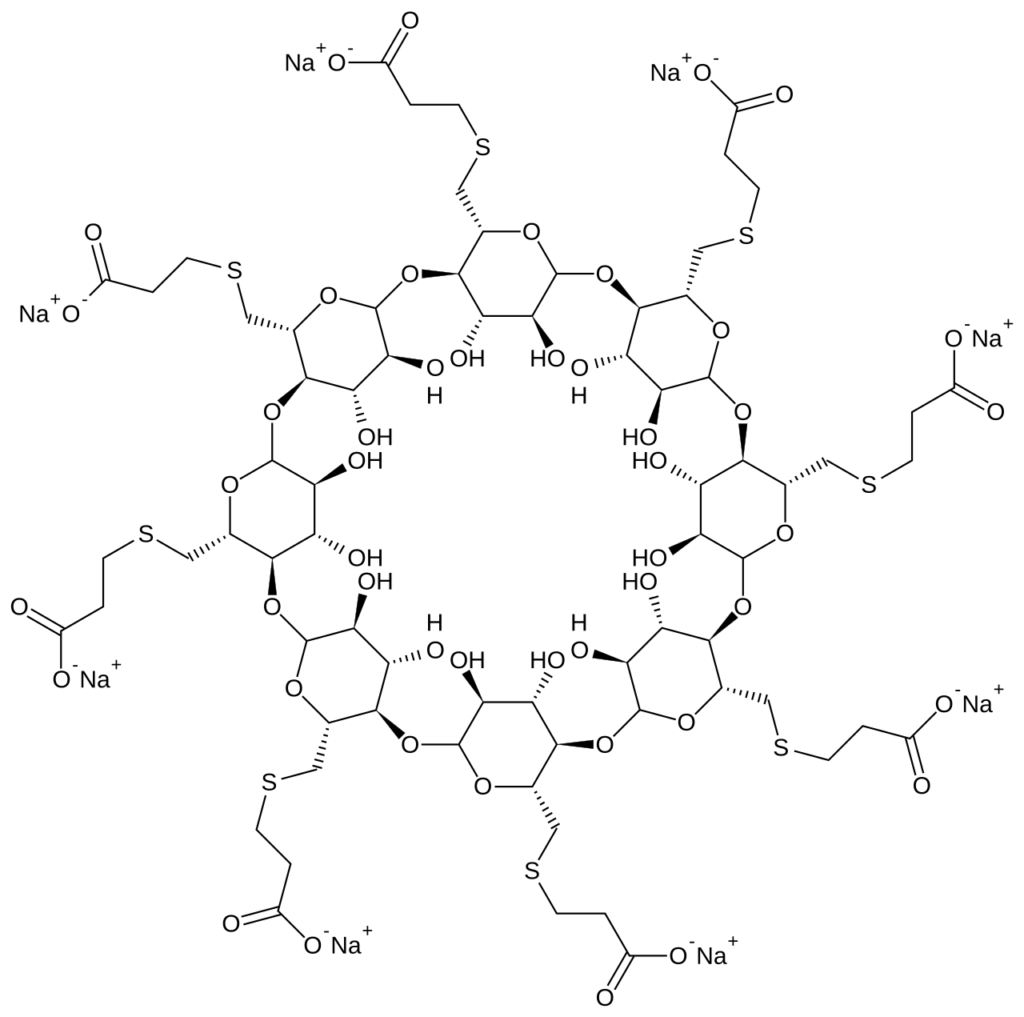

Last week, the Federal Circuit affirmed, in a precedential opinion, a District Court’s finding that PTEs add up to five years of additional protection onto the original patent’s issue date, even if that patent is reissued at a later date. A patent owner may file for a reissue patent to correct errors in the original patent. A reissue renders the original patent “dead.” Here, Merck filed a patent (“the ’340 patent”) on “sugammadex,” which issued on December 30, 2003, and was set to expire on January 27, 2021. On April 13, 2004, Merck applied for FDA approval of sugammadex. While the FDA approval was pending, Merck filed for a reissue, in 2012, for the ’340 patent to add narrower claims, and the reissue patent issued on January 28, 2014. The FDA cleared sugammadex on December 15, 2015, which meant that Merck “could not market sugammadex for nearly twelve years of the ’340 patent’s original term.” Under these facts, Aurobindo (generic manufacturer) argued that instead of the maximum 5-year PTE resulting from the period between December of 2003 (original issuance) to December 2015 (FDA approval), Merck should have only been entitled to a PTE between January 2014 (reissue issuance) and December 2015 (FDA approval). The Federal Circuit declined to accept Aurobindo’s argument. The Federal Circuit reasoned that adopting the generic manufacturers’ interpretation would undermine the Act’s purpose by denying full compensation for the regulatory delay.

Again, Hatch-Waxman seeks to balance the interests of the name-brand drug and the generic drug manufacturers. The Federal Circuit’s holding finds that pharmaceutical patentees are free to file reissue applications to correct errors without concern that their patent terms may be shortened. On the other hand, as the Federal Circuit noted, pharmaceutical patent challengers should be aware of the “difficult questions” that arise out of this holding: to the extent that a reissue patent “corrects” its claims to encompass a drug that was not previously covered by the patent, the pharmaceutical patent holders could feasibly extend protections on a certain drug by incorporating it in a reissued patent. This opens a potential loophole if the reissued patent covers a different drug than the original patent because patentees can seek PTE for the reissue patent, even if FDA did not delay the release of the drug covered by the reissue. However, the Federal Circuit did not confront these difficult questions, as Merck’s reissue had narrower claims.