On August 26, 2024, the Western District of Wisconsin issued a decision adjudicating a number of motions in a case involving a thicket of intellectual property claims and counterclaims. Fiskars Finland OY AB and Fiskars Brands Inc. (collectively, “Fiskars”) sued Woodland Tools Inc. and its affiliated parties (“Woodland”), asserting design patent infringement, false advertising, trade secret misappropriation, and related state claims concerning the parties’ competing lines of gardening tools. Woodland counterclaimed for false advertising and tortious interference. The parties filed cross motions for summary judgment and motions to exclude expert opinions. The court significantly trimmed down the case, leaving for trial only a portion of Woodland’s false advertising counterclaim. A key part of the decision focused on the Court’s exclusion of Fiskars’ design patent expert.

The Court found three issues that rendered Fiskars’ expert’s opinion “unhelpful to the jury” and excluded it under Daubert. First, the expert used only a single piece of prior art, what he deemed “the closest,” in a three-way comparison of the accused product, the patented design, and prior art. The Court noted that “Egyptian Goddess contemplates that the prior art is likely to be a set of references,” and the expert’s use of only one reference “systematically understates the similarity of the patented design to the prior art, thereby improperly broadening the scope of protection for the patented design.” This is reminiscent of the Federal Circuit’s recent decision in LKQ Corp. v. GM Global Technology Operations LLC, where an en banc Federal Circuit held that KSR International Co. v. Teleflex, Inc. overruled the strict Rosen-Durling test for obviousness. The expert’s three-way infringement comparison using only a single reference, like in LKQ, “improperly broaden[ed] the scope of protection for the patented design.”

Second, the expert’s opinion misapplied functionality law. Any feature of a design that is “primarily functional” is not protected by a design patent. But the expert stated that a feature of the design is functional only if there is “only one” available design to serve that function. The expert made no further effort to see if the design encompassed both functional and ornamental elements or exclude any functional elements from his analysis. Finally, the opinion was too conclusory: the expert set forth a series of side-by-side images and then recited a conclusion without any explanation of how his comparisons related to his conclusion that the accused products infringed on the design patent.

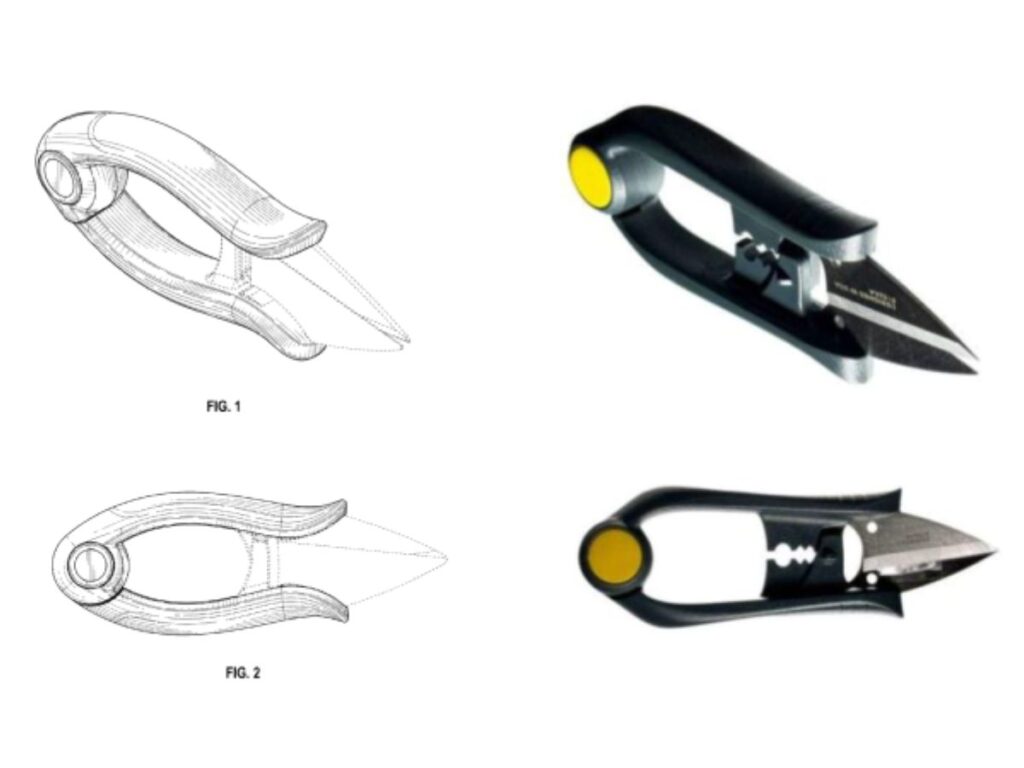

In its 63-page opinion, the Court went on to, among other things, hold that “no reasonable jury could find that a hypothetical ordinary observer, familiar with the prior art, could find the accused product is substantially similar to the design claimed by the ’969 patent” (pictured) or to that in the ’828 patent.

This is at least the second case this year closely scrutinizing the scope of design patent protection vis-à-vis prior art. Parties dealing with design patents—both in prosecution and litigation—would do well to recognize the importance of assessing multiple prior art references in an evolving field of law.