In a highly anticipated ruling, the Supreme Court found that the Andy Warhol Foundation (“AWF”)’s licensing of “Orange Prince” to Condé Nast was not “fair use” of a Lynn Goldsmith photograph that served as the basis for Andy Warhol’s Prince Series. In affirming the Second Circuits’ ruling that the “purpose and character” of AWF’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph did not militate fair use, the Supreme Court clarified that “transformativeness” under the first fair use factor focuses on changes to the purpose of the work (and not just its aesthetics or subjective interpretation), and that transformativeness cannot displace analysis of other relevant factors.

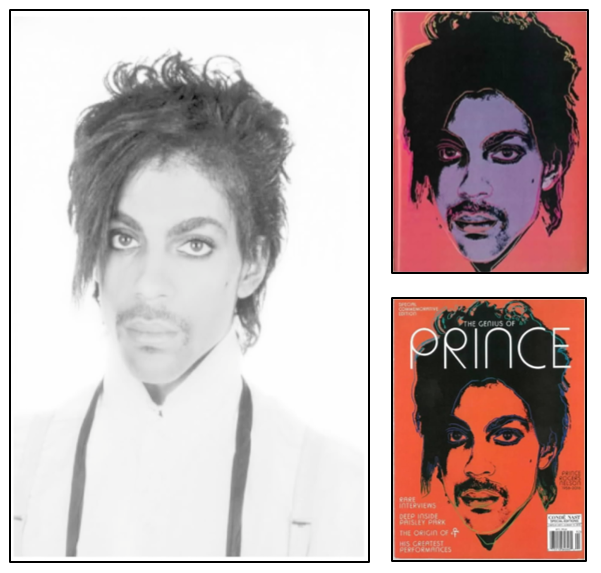

Goldsmith, a leading professional photographer of rock and roll musicians, took a series of portrait photos of Prince in 1981. In 1984, Vanity Fair licensed one such photo on a one-time basis for use as an “artist reference” in a story about the musician. The magazine then hired Warhol who created a silkscreened image using the photo. When Vanity Fair published the resulting work, “Purple Prince,” it credited Goldsmith for the “source photograph.”

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol also used Goldsmith’s photo to create fifteen more works, collectively known as the “Prince Series.” After Prince’s death in 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent company, Condé Nast, sought to publish a special edition magazine commemorating Prince. Initially, Condé Nast contacted AWF to reuse “Purple Prince,” but upon learning of the Prince Series, instead elected to license “Orange Prince” for $10,000. This time, Goldsmith was neither credited, nor compensated. Goldsmith informed AWF that she believed the use of her photo infringed her copyright. AWF then sued Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment that AWF did not infringe or, in the alternative, that Warhol’s use constituted “fair use.”

The fair use doctrine is an affirmative defense against copyright infringement and reflects congress’s intent to balance the promotion of creativity with the protection against undue restrictions on copying in order “to promote the progress of science and the arts without diminishing the incentive to create.” The Copyright Act enumerates four factors for courts to consider in determining whether a use is “fair.”[1] The first factor, the only one addressed by the Supreme Court’s opinion, asks, “whether the new work ‘merely supersedes the objects’ of the original creation (supplanting the original), or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character.”

The District Court granted AWF summary judgment of fair use seemingly based on the aesthetic and artistic merit of Warhol’s work. The District Court found Warhol’s Prince Series was “transformative” because it “transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic larger-than-life figure” such that “each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than a photograph of Prince.” The District Court then relied on that finding to discount the importance of the other fair use factors “because the Prince Series works are transformative,” “Warhol removed nearly all the photograph’s protectable elements,” and that the Prince Series were not market substitutes for Goldsmith’s works. On appeal, the Second Circuit reversed, holding that the two works are substantially similar and that all four fair use factors in fact favor Goldsmith.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari on only the narrow question of “whether the first fair use factor … weighs in favor of AWF’s recent commercial licensing to Condé Nast.” Much of the dissonance between the majority opinion and the dissent stems from the Justices’ widely diverging interpretations of what the first fair use factor is asking courts to examine. More specifically, the Court focused on the meaning and significance of whether a use of a copyrighted work was “transformative” of the original. The dissent subscribed to AWF and the District Court’s understanding that the first factor concerns the extent to which Warhol’s work (i.e. the Prince Series) “transformed” the aesthetic and artistic meaning of Goldsmith’s photograph, whereas all seven other Justices emphasized that it is how the work is used that matters for fair use, and not its artistic significance or the artist’s subjective intent.

The term “transformative” entered the vernacular of copyright jurisprudence via a 1990 Harvard Law review article authored by Judge Pierre N. Leval, then a District Court Judge at the Southern District of New York.[2] In that article, Judge Leval argued that the essence of the “character and purpose” portion of the first fair use factor was that the use “must employ the quoted matter in a different manner or for a different purpose from the original.” Id. This philosophy was then adopted by SDNY in 1991[3], the Second Circuit in 1993[4], and the Supreme Court in 1994.[5] However, unlike the AWF District Court’s interpretation, these early cases all focused on how the accused work was being used (e.g. whether they commented on or criticized the copyrighted work) and not their artistic merit.

So how, then, did courts detour into the business of art critique? The majority identified the culprit to be a paraphrase in Campbell of Judge Leval’s article stating that a transformative use is one that “alter[s] the first [work] with new expression, meaning, or message.” It is true that the “meaning of a secondary work, as reasonably can be perceived, should be considered to the extent necessary to determine whether the purpose of the use is distinct from the original[.]” However, “Campbell cannot be read to mean that § 107(1) weighs in favor of any use that adds some new expression, meaning, or message” because that would obliterate the copyright owner’s right to prepare derivative works. To make “transformative use” within the meaning of the first fair use factor, “the degree of transformation … must go beyond that required to qualify as a derivative.” Here, the purpose for which Orange Prince was licensed to Condé Nast and the purpose for which Goldsmith licensed the original Prince photograph are similar: provision of a visual depiction of Prince to accompany a magazine article on Prince.

The Supreme Court emphasized the importance of considering and balancing all parts of the first fair use factor. The first factor considers the degree to which the “purpose and character” of the accused use is different from (i.e. “transformative” of) that of the use of the original work. “The larger the difference, the more likely the first factor weighs in favor of fair use.” But transformativeness alone is not dispositive. The court should also consider whether the use is commercial or non-profit, but again, that alone is not dispositive; it must be weighed against the degree to which the use is transformative. If the “original work and the secondary work share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is of a commercial nature, the first factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying.” One possible justification for a use might be if copying is reasonably necessary to achieve the user’s new purpose. The AWF District Court erred by interpreting transformation so broadly that it swallowed up a copyright owner’s exclusive right to create derivative works, and then elevated transformativeness above all other aspects of the first factor (commercial use and justification) and other fair use factors.

[1] The four “fair use” factors in § 107 include “(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.”

[2] Leval, Toward a Fair Use Standard, 103 Harv. L. Rev. 1105, 1111 (1990).

[3] Basic Books, Inc. v. Kinko’s Graphics Corp., 758 F.Supp. 1522, 1530 (S.D.N.Y. 1991) (copying excerpts of books for compilation into university course packets was not a fair use).

[4] Twin Peaks Productions, Inc. v. Publications Int’l, Ltd., 996 F.2d 1366, 1375‑76 (2d Cir. 1993) (book disclosing detailed plot summaries of a television program without any critical commentary served no transformative purpose and was not a fair use).

[5] Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 578-580 (1994) (holding that the Second Circuit erred by cutting its inquiry into the first factor off upon finding the allegedly infringing use was of a commercial nature and explaining that a parody of a song could be fair use as “parody has an obvious claim to transformative value,” e.g., by “shedding light on an earlier work”).