On March 24, 2023, the Southern District of New York held that the Internet Archive (“IA”)’s digitization and lending online of the Hatchette Book Group (“Publishers”)’s copyrighted physical books infringed Publishers’ copyrights and was not a fair use.

IA is a non-profit organization that allows patrons to check out eBooks through an online open library just as one would physical books at a traditional library. IA digitally scanned millions of public domain and copyrighted print books, locked the copyrighted books in containers, and made digital copies available on IA’s websites via “Controlled Digital Lending” (CDL). Under CDL, for each copy of a book IA owned, it could loan only one digital copy at a time.

On June 1, 2020, Publishers sued IA for infringing their copyrights in 127 works and challenged this lending model. The parties filed cross-motions for summary judgment (“SJ”). IA did not contest infringement but argued its use fell within the “fair use” exception. The Court disagreed, finding IA’s use not a fair use largely because it did not add something new to alter the expression or meaning of the work; it merely “space-shifted” the work from physical to digital form. As such, the Court granted Publisher’s SJ motion for copyright infringement, and denied IA’s SJ motion asserting that its use was a fair use.

The decision mainly focuses on fair use, but that is not the real reason IA’s case imploded. Fair use is a necessary but unreliable safety net for avoiding unwanted edge cases where copyright law fails to fulfill its purpose. Physical libraries rely not upon fair use (much less publisher cooperation) to protect their book-lending practices, but the ironclad protection of the “first sale” doctrine codified at 17 U.S.C. § 109. Generally, the doctrine guarantees an owner of a copy of a copyrighted work the right to dispose of that copy as they please. However, it does not enable reproduction of the work or creation of derivatives.

IA tried to apply to the digital medium the physical library model of lending the copy it owns. However, every act of using, moving, or viewing an eBook involves copying (i.e. reproduction) because of how computer devices work. Even in cases such as Capitol Recs. v. ReDigi, where ReDigi took extreme steps to make transfer of a digital good replicate a physical handoff by ensuring only one copy of the digital good existed at a time, courts still found it to constitute reproduction not protected by the first sale doctrine. Thus, IA could not simply buy an eBook and ‘lend the copy it owns.’ IA tried to circumvent this by making its own eBooks, but that, the Court found, created infringing unauthorized derivative works.

This case is another canary in the coalmine for copyright’s regressive effects on the public library model. The first sale doctrine fell behind the technological curve. The law disallows digital equivalents of actions allowed in the physical realm (e.g. handing someone a book). This is a problem: entrenched legal doctrines exist for a reason. Unshackled in the digital world, publishers can and do restrict use of works, treat libraries differently, and extract more profits from libraries and users alike at the cost of the free flow of knowledge. This will worsen as digital supplants print (even as publishers’ production costs plummet)

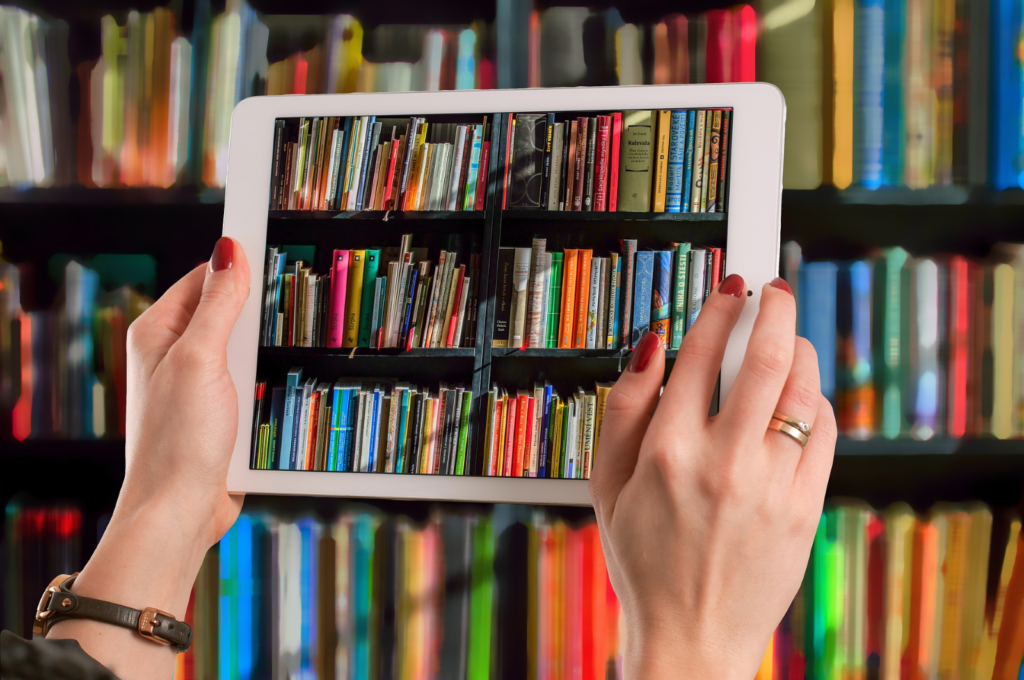

Photo by Gerd Altman via Pixabay