In an appeal before the Federal Circuit, plaintiff People.ai argued to no avail that the Northern District of California erred in its finding of invalidity for a set of business-analytics software patents under 35 U.S.C. § 101. The plaintiff appealed, claiming that its patents did not contain patent ineligible subject matter and, if they did, included distinct, inventive concepts. Unfortunately, People.ai couldn’t automate the court’s response, and the Federal Circuit affirmed the District Court, explaining that automating a longstanding, manual process fails the Section 101 Test as set forth in Alice/Mayo.

Section 101 states that “[w]hoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.” Courts have long held that certain categories fall outside the scope of patent-eligible subject matter under Section 101, and the Supreme Court established a two-step test for determining whether claims of a patent fall outside of the scope in its decisions in Alice Corp. and Mayo Collaborative Servs. These exceptions include laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas. The two-step test, called the Alice/Mayo Test for short, asks (1) whether the claims are directed to a patent ineligible concept (one of the exceptions) and (2) whether the claims contain an inventive concept sufficient to transform the concept into a patent-eligible application. The Federal Circuit found against the patentee on both steps.

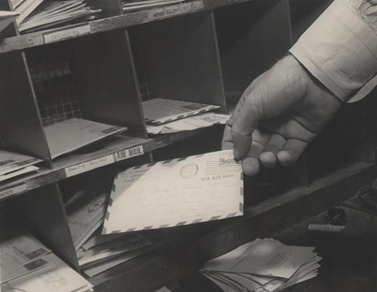

The Federal Circuit reviewed the case de novo, but agreed entirely with the District Court that the claims at issue were directed to a patent ineligible concept, namely, the abstract idea of data processing by restricting certain data from further analysis based on various sets of generic rules for each patent. The Federal Circuit agreed with the District Court’s description of the claims to be a type of filtering traditionally used in a corporate mailroom or by a salesperson who “discards the junk mail before updating the business files she maintains with relevant communications.” People.ai tried to distinguish their claims from an abstract concept, the process conducted by humans, based on (1) the specificity of the steps, (2) the removal of subjectivity, and (3) the limitations of humans. People.ai then argued that its claims were transformed into patent-eligible concepts based on (1) the ordered combination, (2) the filtering rules, and (3) the node profiles. The Federal Circuit disagreed at both steps, explaining that the claims of the patents did “not claim a different method than that traditionally used long before the application of computer technology to the problem of sorting correspondence,” and explained that “the abstract idea cannot provide the inventive concept.”

Businesses looking to patent this sort of technology must demonstrate an inventive concept; that a computer process helps do something faster or more efficiently is simply not enough.

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY