On September 9, 2021, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) found that use of a catalog description of a prior art product as a prior art reference in an IPR proceeding does not create 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2) estoppel as to the underlying prior art product. Further, the CAFC denied mandamus because DMF, Inc. (“DMF”) failed to show that a post-judgment appeal is an inadequate remedy for asserting a statutory estoppel argument or that it had a “clear and indisputable” right to relief.

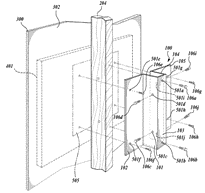

DMF is the owner of U.S. Pat. No. 9,964,255 (the “patent-in-suit”), which is directed to certain compact recessed lighting products. DMF sued AMP Plus, Inc., d/b/a Elco Lighting (“Elco”) in the Central District of California, alleging Elco infringed various claims of the patent-in-suit. Elco filed an inter partesreview (IPR) petition[1] arguing that the claims were invalid based on a product catalogue featuring a Hatteras lighting product (“Hatteras catalog”). DMF argued that the claims were non-obvious because Elco “mixed and matched” various products from the catalog. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) agreed with DMF and found the claims non-obvious. The case reverted to the district court and DMF moved, under § 315(e)(2), to bar Elco from asserting invalidity based on the actual Hatteras product. Section 315(e)(2) provides that the “petitioner in an inter partesreview of a claim in a patent … may not assert … in a civil action … that the claim is invalid on any ground that the petitioner … reasonably could have raised during the inter partes review.” The district court’s evaluation focused on whether differences that were “germane to the invalidity dispute” existed between the Hatteras product and its catalog description. The district court found the Hatteras product to be substantively different; specifically, the court pointed to DMF’s prior argument that Elco “mixed and matched” various products in the catalog, and that the description within the Hatteras catalogue failed to disclose all of the product’s features. DMF then petitioned the CAFC for a writ of mandamus challenging the ruling that Elco was not statutorily estopped from raising this particular ground of invalidity.

DMF is the owner of U.S. Pat. No. 9,964,255 (the “patent-in-suit”), which is directed to certain compact recessed lighting products. DMF sued AMP Plus, Inc., d/b/a Elco Lighting (“Elco”) in the Central District of California, alleging Elco infringed various claims of the patent-in-suit. Elco filed an inter partesreview (IPR) petition[1] arguing that the claims were invalid based on a product catalogue featuring a Hatteras lighting product (“Hatteras catalog”). DMF argued that the claims were non-obvious because Elco “mixed and matched” various products from the catalog. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) agreed with DMF and found the claims non-obvious. The case reverted to the district court and DMF moved, under § 315(e)(2), to bar Elco from asserting invalidity based on the actual Hatteras product. Section 315(e)(2) provides that the “petitioner in an inter partesreview of a claim in a patent … may not assert … in a civil action … that the claim is invalid on any ground that the petitioner … reasonably could have raised during the inter partes review.” The district court’s evaluation focused on whether differences that were “germane to the invalidity dispute” existed between the Hatteras product and its catalog description. The district court found the Hatteras product to be substantively different; specifically, the court pointed to DMF’s prior argument that Elco “mixed and matched” various products in the catalog, and that the description within the Hatteras catalogue failed to disclose all of the product’s features. DMF then petitioned the CAFC for a writ of mandamus challenging the ruling that Elco was not statutorily estopped from raising this particular ground of invalidity.

Regarding mandamus, the CAFC noted that it is “reserved for extraordinary situations.” Gulfstream Aerospace Corp. v. Mayacamas Corp., 485 U.S. 271, 289 (1988). Under the All Writs Act, the CAFC may issue a writ if: (1) there is no other method of obtaining relief; (2) they have a “clear and indisputable legal right;” and (3) a “writ is appropriate under the circumstances.” Here, the CAFC denied mandamus because DMF was unable to demonstrate that a “post-judgment appeal is an inadequate remedy” and had not met its “heavy burden” of showing the district court’s ruling was “clearly and indisputably erroneous.”

Although non-precedential, this case is important because it limits the scope of the statutory estoppel associated with seeking IPR before the PTAB; acknowledges that there can be a difference between a publication disclosing a prior art product and the product, itself; and reminds us of the limited nature of mandamus.

[1] An IPR petitioner may seek to invalidate claims based on “prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.” 35 U.S.C. § 311(b).